Ken Mignosa completed the California Triple Crown in 2017 with a swim from Oxnard to Anacapa Island. The triple crown includes a swim across the length of Lake Tahoe (Camp Richardson to Incline Village in just over 14 1/2 hours), and a swim from Catalina Island to the Mainland.

Ken said: of “I completed the California Triple Crown on 28 October, 2017 with a swim from Oxnard to Anacapa Island. It’s about a 12 mile swim that took me a little over 9 hours. Most of the way I swam against a 1kt current, and part of the way there were high winds & large swells. I remember the wind pushing myself and my pilot vessel close to the oil rig “Gina”. We got close enough that some of the folks working the rig waved at us. Upon arriving at Anacapa in the morning the weather calmed, and the water was clear. After completing the swim my entire crew joined me in the water to swim through the arch at the west end of Anacapa and the cave within the arch. The western end of Anacapa is surrounded with a vibrant kelp forest, and with visibility exceeding 10 meters there was quite a lot of life to see. This initial exposure to beautiful water, good visibility, and abundant fauna is what made me interested in returning to the Santa Barbara Channel for more swims.”

In 2018, I returned for a swim my son dubbed “Ken’s Cruz”. This was the swim around the south side of Anacapa to Santa Cruz, then back to Oxnard. I am the only swimmer to have completed a round trip Santa Cruz Island, and that swim earned me a nomination for male swimmer of the year from the World Open Water Swimming Association (WOWSA). In 2019, I returned again for “Ken’s Tour de Channel Islands”. I swam from San Miguel Island, to Santa Rosa Island to Santa Cruz Island. This was a swim of about 43 miles and 35 hours that was cut short by gale force Santa Ana winds. I had planned to swim on to Anacapa, and end up in Oxnard. I am currently planning to return to the Santa Barbara Channel in 2022. If conditions allow, I’ll attempt to be the first person to have swum between the mainland and all the northern Channel Islands by completing swims between the mainland and San Miguel Island as well as Santa Rosa Island.

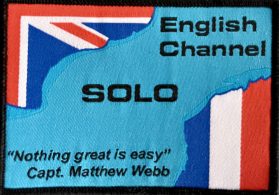

And completed the Triple Crown of Open Water Swimming in 2021 when he swam the English Channel in 14 hours, one minute, June 18, 2021, having already completed the swims from Catalina Island to the Mainland (see above) and swam around Manhattan Island in New York city in just under 8 hours.

First, two photos from the swim around Manhattan Island, followed by three photos from the English Channel swim:

Ken started with shorter swims, such as the Sharkfest swim from Alcatraz to San Francisco in 2006.

below, Ken about to be the first person in the race to jump off the ferry

Many De Anza swim students have completed the same ocean swim race.

Ken became an American Red Cross lifeguard in my class at De Anza College, and yours truly also mentored him as a Lifeguard Instructor and then as a Lifeguard Instructor Trainer.

Ken volunteered as a lifeguard for years at the Silicon Valley Kid’s Triathlon, held at De Anza college.

At this triathlon, that De Anza college trained lifeguards and swim students volunteered at for ten years, we swam with the youngest athletes. Ken is in the upper center portion of this 2009 photo:

A guard at this race should anticipate an inexperienced athlete coming into the wall and be ready to put a rescue tube between the swimmer’s head and the wall to protect their head, as Ken did here at the 2007 race:

and here, Ken on a break during the 2010 Kid’s Triathlon, hanging out with Sharkie (the San Jose Sharks’ hockey team mascot):

and volunteered at multiple Alcatraz to San Francisco swims and triathlons.

here a photo of lifeguard volunteers, with Ken when he swam, October 15, 2006 AlcaTri triathlon:

L= De Anza College trained lifeguard, F= friend, S= swimmer

(left to right) front row: Lee Merschon (L), Amit Avitan (F)

Middle row: Shannon Mathey (L), Debbie Adams (L),

Karen Fabrizius (L), Sylvia (Lam) Feury (L), Ken Mignosa (S), Mary Donahue (L)

back row Brian Harness (L), David Feury (F), Donny Mackin (F), Alan Ahlstrand (L), Ronnie Cziska (F)

photo below by Selena Lum

Alcatri June 24, 2007 lifeguards:

front: Danoush Ahmadi

back, left to right: Ken Mignosa, Mary Donahue, Alan Ahlstrand, Debbie Adams, Shannon Mathey, Keith Hubbard, Glenn Wheatland, Sherry Fong (too late for the picture: Joe Lloyd).

You can read more about volunteering at these races at:

Escape from Alcatraz ‘Sharkfest’ swim volunteering

and see tips for lifeguarding (and swimming) open water swims and kid’s triathlons.

First below, his story of his English Channel swim, followed by links to other articles.

Lucky English Channel Swim by Ken Mignosa

It’s about 6:30 on Saturday morning, 19 June, 2021, and I should be in bed. However, my mind is whirling with thoughts about yesterday’s events. Yesterday at about this time, I was swimming back to a boat called Masterpiece from a beach in France. I had just completed a swim of the English Channel. I’m trying to wrap my head around the fact that I swam the English Channel. I know there are others who have swum this course. Some have done it multiple times, and some have gone two ways, three ways and even Sarah Thomas’ incredible 4 ways. In the scheme of things it’s not that big a deal. Even within the group of sanctioned marathon swims that I’ve completed over the last few years, the English Channel was neither the hardest nor the longest swim I’ve done. There is something about all the issues that surround the swim that make it unique. There are plenty of obstacles to put one off of attempting the swim no matter how accomplished a marathon swimmer one might be. For starters the swim is expensive. In 2021 the boat fee alone was over £3,000. To put that into some context, In USD that’s more than I’ve paid to setup a boat for a swim more than twice as long and harder than the English Channel. In addition, the cost of simply getting to the east coast of the UK can be prohibitive. Airfare, lodging and food for a stay of about a week and a half can be quite costly. If one chooses to bring crew from home, that adds on the cost of their airfare, lodging and food. And to make the expense just a little higher, I completed my swim during the COVID pandemic. This meant that the trip to the UK started with a 10 day quarantine before I could leave a rented flat and do, well, anything. While in quarantine there were 3 COVID tests that had to be paid for and submitted. Also while in quarantine all food, and anything else one might want, had to be delivered as the only outing allowed was to drop a COVID test in the mail. After one has somehow justified the expense of the swim there are logistical hurdles to overcome as well. An English Channel swim is setup to happen during a window of about a week, usually during a neap tide. During that week swimmers and crew are supposed to be ready with 4 hours notice or less to go and swim at any time. During the swim window, the swimmer and crew are always on “standby”. Pilots will usually take up to 5 bookings per swim window. I was the 3rd of my pilot’s bookings. This was actually an improvement as I originally booked to be 4th, but over the year plus since I booked the boat someone had dropped out, and I moved up a spot. I have often read about how the swim route is difficult due to the currents, tides and vessel traffic. First, The swim is perpendicular to the current, and the swim is almost never completed as a straight line between England and France. Usually the swim takes on an S shape as the current pushes the swimmer one way and then another in the channel. Second, the tidal changes in the channel are pretty extreme. During the swim windows on neap tides the tidal change drops to a mere 5-6 meters differential between high and low tides. Outside of a neap tide, the tidal changes are much greater. Third, the English Channel is one of the busiest shipping channels on the planet. So vessel traffic can be an obstacle to getting across the channel.

All of that said, the challenges of current, tide and vessel traffic are of little concern to the swimmer and swim crew. They are issues with which the pilot vessel’s crew must contend. The good pilots, and most of the registered channel swim pilots are really good, navigate these potential obstacles with ease. At least it looks like it’s easy if you’re not the one piloting the boat. Another challenge for any marathon swim can be arranging a crew, and the pandemic made my original crew plans impossible. I had planned to take along a couple of people I know from the South End Rowing Club as crew for the swim. However, the expense of taking 2 people along, and quarantining for 2 more people and COVID tests for two more people was too costly. So I ended up hiring crew locally. I am incredibly fortunate to be involved in the active marathon swimming community at the South End Rowing Club. Through friends there, I received referrals to former channel swimmers and channel crew people who lived in the UK and could help. I ultimately made arrangements with 2 of those referrals: Dr. Nicholas Murch and Deborah Vine. They did all the heavy lifting – sometimes literally as my gear was heavy – for this swim. The pilot that I booked to guide me across the English Channel was also a result of a referral from friends at the South End Rowing Club who had already completed English Channel swims. The expenses and logistical challenges are daunting for this swim. The swim itself actually wasn’t that difficult. I should qualify that by saying it wasn’t that difficult compared with other swims I’ve done. The real work was done by the pilot and the swim crew. My task was simple – just keep swimming. While I said the swim wasn’t that difficult, part of what made it that way was preparation. As training for the swim, I swam hundreds of thousands of meters in San Francisco Bay. I swam with the current (downhill), against the current (uphill), in the rain, in the wind, in the dark, in the cold. My “short” swims were about 2 hours, and most of my training swims were over 3 hours. In the months leading up to the swim it was rare for me to do a swim of less than 10km. The Channel Swimming Association is a group that sanctions English Channel Swims, and they require a 6 hour qualifying swim before they’ll accept an application to swim the English Channel. I completed mine in 11°C water, and it was not the only 6 hour swim I did as part of my training. As my swim window approached I worried less about my swim volume and ability to deal with adverse conditions, and more about the water temperature. While I was training in what many consider to be a chilly San Francisco Bay, the English Channel was colder. About a month and a half before my English Channel swim window, the bay started to warm up. It was about 14°C by the time I left for the UK. Meanwhile, the UK had had an unusually late winter and an even later thaw. One month before my swim window the water temperature in the English Channel was 9°C. Even my 11°C degree qualifier was warm by comparison. Thankfully, by the time I reached the UK the water temperature was around 13°C. By the time my wife and I finished our quarantine the temperature had gone up another degree or so, and on the French side of the channel the temperature was a little warmer still. I had justified the expense, I had tackled some of the logistical challenges for the trip to the UK during a pandemic, and now all that remained was to make it through a quarantine, and hope that I’d get to swim, and, even more, complete the swim.

After our arrival in the UK for our quarantine, my wife and I watched the wind forecast avidly. Wind is pretty much the limiting factor for many marathon swims, and the English Channel is no exception. If the wind is too great, the swim becomes dangerous for the swimmer, crew, and pilot vessel. To make the swim safe the wind had to be mild enough and in the correct direction to suit the pilot. As with weather anywhere, the wind forecast was volatile. My wife and I kept looking for periods of light winds that were long enough to complete channel swims. I knew that there were 2 relay swims ahead of me, and they’d get first choice of times with good conditions. On the first day of the swim window, conditions were great and the first relay swim went out and completed their swim in a little over 14 hours. A couple of days later good conditions were available again, and the second relay swim went out and completed their swim. If conditions allowed, it might be possible for the 3rd swimmer – me – to swim. That volatile wind forecast made setting the swim time difficult On 16 June, I received a few hours notice that the pilot saw a suitable window for my swim to begin at 2:00AM on 17 June. I was already mostly packed up for the swim, but I finished packing, and tried to take a nap. I’m usually pretty apprehensive in advance of a swim and sleep is elusive. So while I didn’t sleep, I did lie still and rest. The pilot said he’d give a final confirmation at 1:00AM. When the pilot contacted me at 1:00AM the wind forecast had changed, and it was no longer possible to do the swim safely. The swim was off, and a new decision would be made around midday on 17 June. Mid-day on 17 June, the pilot contacted me with good news. The swim could go forward, and me and my crew were to meet at the Folkestone harbour at 2:30PM. On 17 June, Nick Murch was already staying in Folkestone in our rented flat, and Deborah Vine was on her way to Folkestone. Deborah had hoped that the midday decision would be positive, and decided to head to Folkestone ahead of that decision. Because of the false alarm, and the fact that the wind forecast at 1:00AM on 17 June looked pretty bad, I had assumed I’d have to wait longer and hope for a later low wind time for my swim. As a result, I relaxed, and I slept. So when the text came with news that the swim could happen, I was pretty well rested – for a change. A bunch of last minute preparation was completed, and we loaded up Nick Murch’s car with all the swim stuff (feeds, water, medications, light sticks, rope, tape, etc.), and made the 5 minute drive to the Folkestone Harbour. When we arrived at the harbour, the swim observer and pilots were already on the boat making preparations to depart. The pilots of the vessel “Masterpiece” are a father and son team, Fred (father) and Harry (son) Mardle. Harry came over in a rowboat to the stairs leading down to the harbor, and he took most of the swim stuff over to Masterpiece. Before Harry came back to pick up me and my crew, my wife and I said our goodbyes and she took a picture of me and my crew. When Harry came back he took the rest of the swim stuff and me and my crew out to Masterpiece. We climbed aboard, had a safety briefing, and headed out to the starting point for my swim just south of Dover at Samphire Hoe. During all the time we were at the harbour, and motoring out to Samphire Hoe, me and my crew were amazed that there was no wind, and the water was very still. It was amazing, because the forecast had predicted that the swim would start out windy, but that the wind would die down during the swim. The forecast had been wrong in my favor – a lucky start.

By the time we arrived at Samphire Hoe I was sunscreened and lubed in the places where I sometimes chafe during long swims. Once Masterpiece was put in neutral gear, and I was to jump off the boat and swim to shore. Like many marathon swims, the English Channel swim starts and ends with the swimmer fully out of the water. I spent a moment thinking what madness had led me to do this swim, and then I jumped off the boat and swam to the shingle beach. By shingle I mean a beach of mid-size pebbles. I unsteadily got out of the water trying to keep my balance on the uneven surface. When I was fully out of the water, I turned to Masterpiece, waved to the boat, a horn was sounded, and my swim began at about 3:30PM on 17 June. I got to start my swim in ideal conditions, no wind, some sunshine, and comfortable 14°C water. After 50 meters of butterfly, I straightened my swim cap, I switched to freestyle, and I was off. The first several hours were unremarkable. There was little to see as I headed away from the white cliffs, and the swimming was smooth and easy with flat water and no wind. As the day progressed it got cloudy. I kept swimming, and all I saw every time I turned to breathe was clouds until it got dark. Around dusk I started getting stung by jellyfish. The light was dim enough, and the water was murky enough that I never saw what was stinging me. It felt like the sting of sea nettles. These brownish jellies have a relatively mild sting, and the pain of the sting does not last long. I’ve been stung by sea nettles before without incident. However, I bring epi pens on my swims just in case I have a severe allergic reaction. Also sometime around dusk a dogfish swam beside me. A dogfish is a small shark, and my crew attempted to get pictures of the fish. However, the light was too dim for the photography. I was unaware of my fish company, but Deborah and Nick both told me that my hand ran right along the fish at least once while the dogfish was beside me. Sometime after sunset the wind picked up a little and added some chop to the water forcing me to be careful about my breathing. The chop was not nearly as bad as conditions in which I had trained in San Francisco Bay, and I didn’t find it to be much of a problem. I kept swimming. A few hours later at first light I thought I saw a lighthouse, but I thought I had at least 5 hours more left to swim, so I assumed what I saw was something else. It turned out what I saw was the lighthouse at Cap Griz Nez, but I didn’t know that until after the swim was completed. Also sometime after first light the wind died down and the water became mostly calm again. I kept swimming. Two hours or so later my crew informed me that I was getting my last feed, and I had 1 mile to go to get to the beach. I was shocked because I was sure I was nowhere near the end of the swim, and elated because I was going to get to finish my swim and set foot in France. The crew had to tell me several times that my swim was coming to an end because I just didn’t believe it! While I was swimming, Masterpiece set out a RIB and Harry rowed out to escort me to the beach and witness the swim completion. The water was too shallow for Masterpiece to accompany me all the way to shore, and Masterpiece stayed a few hundred meters offshore. I often end my training swims and my sanctioned swims with a few meters of butterfly. I had intended to do that with this swim. However, when I was still about 50 meters from the beach,

the bottom sneaked up on me, and it was too shallow to swim at all. I stood up and walked the rest of the way onto the French beach. The swim ended as it began with me clearing the water fully, and raising a hand until a horn was sounded by the boat. The unofficial time for the swim was 14 hours, 1 minute. I had guessed that this swim would take me 16-18 hours. My actual time was 2 hours shorter than my fastest estimate! It turned out that my average pace for the entire swim was significantly faster than my usual pace. Usually I do about 3km/hour. During this swim I was closer to 3.2km/hour. All I can figure is that I was getting some assistance from the current for significant parts of this swim. I was offered a ride back to Masterpiece on the rib, but I chose to swim back. By the time I finished the swim the wind had begun to pick up again, and I thought it was warmer in the water than it would have been in the RIB. I was welcomed back onto Masterpiece with congratulations and hugs. I proceeded to get changed into dry clothes, put on a heated vest, and put on a swim parka over that. After getting dry and turning on the heated vest I warmed up pretty quickly. Someone on the boat gave me a mug of hot water to help warm me up from the inside. All the while I was getting settled on the boat Fred and Harry were making preparations to leave French waters and head back to Folkestone. Also after I had finished the swim a storm rolled in. Rain and wind got stronger and stronger as we headed west toward England, and the boat ride became very rough. I was tired after my swim, and I had hoped to rest on the boat ride back to Folkestone. The rough conditions made rest impossible, and the building rain made comfort impossible. I took shelter in the small wheelhouse of Masterpiece. The wheel house had two poorly anchored seats that bounced all over the place in the rough sea. However, at least in the wheelhouse I was able to stay dry. I wasn’t sure how I was going to fare for our 3 hour journey back to Folkestone. In another stroke of good luck, conditions calmed enough to allow sleep about 2 hours into our journey back to Masterpiece’s home harbour. The storm that made our departure from France so rough rolled in less than an hour after I completed my swim. Had I taken my estimated 16-18 hours to complete my crossing, I would have been pulled by the pilot before completion as the wind would have made continuing the swim dangerous. Weather for the rest of my swim window was terrible. There were high winds and rough seas with only brief breaks in the rotten conditions. So I ended up completing my swim on the only remaining opening in the weather in almost exactly the right amount of time. I had a very lucky English Channel crossing! To be fair, the crossing was less luck, and more a combination of excellent reading of the conditions by pilots, great support from the crew, and good preparation. This English Channel swim finished the triple crown of marathon swimming for me. The triple crown is a swim from Catalina Island to Palos Verdes which I completed in 2017, a swim around Manhattan which I completed in 2018 and the English Channel crossing.

I learned after my swim that mine was the first non-wetsuit solo swim of the 2021 season. Also on the days of my swim, Masterpiece was the only pilot boat out. So there were no other swims happening when I swam my English Channel. I also learned after my swim that during most of the swim it was foggy, cold and drizzling. So conditions for the crew were worse than they were for me. Deborah and Nick were soaked by the time we returned to Folkestone. As a side note, I am sometimes asked what I think about during these long swims. The many hours with head in the water and no one to talk with can be mentally very taxing. I and others have said that once the physical conditioning for a marathon swim has been sorted out, the actual swim is about 90% mental and 10% physical. If the physical preparation is good, the swimming could almost continue even if the swimmer were only partially conscious. However, the hours of solitude are another matter. As a friend of mine once said, you have to be pretty comfortable in your own head to be able to swim for many hours alone. My thoughts during this swim could be considered meditative. I began the swim simply counting strokes and trying to pay attention to my body position in the water. Without current to intervene, I usually go about 1 meter per stroke: 1000 strokes are equal to about 1 km. A little after 4000 strokes I moved on to repeating rounds of music in my head. I fell back on a tune I’ve had in my head during many of my training swims – Bombasto. It’s a circus march from 1895 by Orion R. Farrar with 4 parts that can be easily mixed and matched. If played as composed by Farrar, the piece takes about 2 and a half minutes. I noodled around with it in my head for several hours. The music that followed Farrar’s was Sergei Rachmaninov’s Isle of the Dead, and then his Symphonic Dances. These pieces too are only a few minutes each, but I fiddled with them in my head for hours. The music in my head was sometimes in the foreground, and sometimes in the background. When the music moved to the background random and not so random thoughts came up. From the not so random category were doubts about the swim. How was my stroke count – I’m usually about 51 strokes a minute (slow for a marathon swimmer)? My stroke count, as it turned out, stayed pretty steady throughout the swim as it almost always does. Was the cold water going to get to me? No, the water temperature was, if anything, a little warmer than the water I had trained in. Would my body hold up as I’d been having trouble with hip flexors and adductors during my training? I had several moments of excruciating pain in my legs, but I swam through them, and I was fine. Would I persevere for the hours that remained of the swim? Apparently that was something with which I needn’t have concerned myself. Might the conditions turn ugly forcing the pilot to pull me? Basically all kinds of doubts about my ability to succeed in this swim. The overriding thoughts were to keep swimming and a refrain of “I didn’t do months of training and all the hassles of setting up a marathon swim during the pandemic to fail” From the random category were a mish mash of thoughts. For example, the night that I had the false alarm that the swim would start at 2:00AM, I had planned to make a mushroom onion cream sauce to go with some chicken. During the swim, I thought about that sauce – the ingredients I’d use, preparation of the ingredients, slicing mushrooms, chopping an onion, sautéing onion and garlic in butter and red wine with herbs, adding mushrooms, quickly tossing the mix in a hot pan, adding some heavy cream and a little Meyer lemon juice, simmering of the final sauce, etc. Not surprisingly, after the swim, I had little interest in actually making the sauce – something about being a little tired and sore. However, during the swim, the cooking gave me something to think about, and odds are that I will make that sauce sooner or later.

Every once in a while and sometimes for a half hour or so, I would let my mind go blank and experience the world around me. At some point during one of these interludes, I thought I heard dolphins underwater. It turns out there was a pod of porpoises not far off. At other times I simply noticed my body moving through and with the water. My thoughts during the swim were, to make a bad pun, shallow. I didn’t come up with solutions to the problems of the world. I simply kept my mind occupied with varied material.

Post Script: On Sunday, 20 June, I was invited to join Nick Murch and a bunch of other folks who get together regularly in Dover to train for long swims. A short swim sounded nice, and Nick said I’d have a warm welcome from the people who swim there. Little did I know how warm a welcome it would be. It was a happy surprise, when all activity stopped as I walked onto the beach. Emma France, the group leader, blew a whistle, and announced that a channel swimmer was present, and a whole bunch of people who were preparing to swim applauded me for a minute or so. Wow! I was overwhelmed! After and during the applause there were congratulations, and I was given 2 English Channel solo swimmer patches.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

Photo during calm water just before sunset:

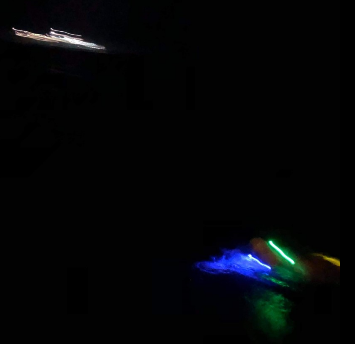

Photo at night. White light on a cargo ship passing by. Ken had a yellow light on his swimsuit and blue and green lights on either side of his head on goggle straps:

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

![]()

Ken also sent me this:

Some of what I’ve written about my swims has been published in the South End Rowing Club newsletter. The most recent newsletter contains a story about a harbor seal encounter and Ken’s Cruz (my round trip Santa Cruz Island swim). These can be found at:

http://serc.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/2019.01-February-2019.pdf

Here is a portion of what he wrote about the seal:

“ . . . The swim started in the dark, and by the

time I reached Fort Mason pier 3, it was first

light. I swam to the foot of pier 3 and then

cut across to pier 2. Shortly after heading

to the end of pier 2 my foot bumped into

something. I assumed it was a bit of debris

in the water as I’ve often bumped into stuff

in the waters of San Francisco Bay. Two or

three kicks later I bumped something again.

A dozen kicks or more later I bumped into

something yet again, and now I started to

wonder what could it be.

When I stopped to look, a small harbor

seal popped up its head at my feet and stared at me.

It looked for a good long while. Somewhere I learned

that staring at pinnipeds is threatening to them. So I

looked away. The seal didn’t seem to be interested in

harming me, and other than nuzzle my feet, it hadn’t

done anything untoward.

The seal continued to follow me to the end of pier

2, around the end, and back toward the foot of pier 2

between piers 2 and 1. I became a little concerned for

my safety, and hoped that by altering course I might

leave the seal behind. I cut across directly to the

western edge of pier 1, aka Gashouse, and the seal

did not follow.

A few minutes later a group of swimmers came

out to Gashouse and we talked about the seal. They

headed back toward Aquatic Park, and I hoped that

the group of swimmers had scared away the seal. I

resumed my Sarah Lap. I swam down to the foot of

pier 1, across to pier 2, and up to the end of pier 2.

There I was met by the same seal. For some

reason—probably abject stupidity—I continued my

Sarah Lap, outlining each pier on the way back. All

the way along I was accompanied by the seal. It

nuzzled my feet. It swam up beside me—leaning into

my right side—and swam along. Sometimes when

it was right up against me I could reach down and

“pet” the seal with my hand. The seal also swam

under me and around me, and sometimes it simply

paralleled me for a few strokes.

At the end of pier 3 I encountered another

swimmer and we talked about the seal. We talked

about heading back to Aquatic Park, but I decided to

complete my Sarah Lap. The seal continued to stay

with me to the foot of Pier 3. It followed along as I cut

across to the old Alcatraz pier. Then it tried a new

game and swam up under my legs, and pushed my

legs up and me forward. I guess I was going too slow

to suit the seal!

The seal stayed with me to the foot of Muni

Pier, near Farnsworth Gap, and followed me about

halfway around to the opening. After this, I neither

saw nor felt the seal any more.

The seal and I ended up spending about 15

minutes together on my way out to Gashouse and

over 40 minutes together on my way back toward

Aquatic Park. . .”

and here, National Park Service photos of seals:

I was the South End Rowing Club swimmer of the year in 2017 – . . .,

in large part due to completing the California Triple Crown of marathon swimming (length of Lake Tahoe, Catalina Channel, Santa Barbara Channel) in under 4 months. . . and my first year of ultra-marathon swimming . . .I wrote an article about that, and it can be found at:

http://serc.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/2018.01-South-Ender-April-2018-color-corrected.pdf

My documented marathon swims can be found at Evan Morrison’s Marathon Swimmers Federation website:

https://db.marathonswimmers.org/p/ken-mignosa/

or Steve Munatones’ Open Water Pedia at:

https://www.openwaterpedia.com/index.php?title=Ken_Mignosa

which includes this:

2018 World Open Water Swimming Performance of the Year Nomination

Mignosa’s Two-way Santa Cruz Island Crossing was nominated for the 2018 World Open Water Swimming Performance of the Year award: Ken Mignosa, known as The Beast, is one very tough, very hardened channel swimmer. Near two-meter white-capped waves did not stop the 54-year-old during his 17 hour 18 minute Catalina Channel crossing and neither did an unprecedented two-way crossing between Santa Cruz Island and the California mainland with an extra swing around Anacapa Island. His 29 hour 22 minute channel swim was the second longest channel swim off the American West Coast in history and the first two-way Santa Cruz Island swim that painstakingly totaled 65.98 km. For successfully completing the second longest solo marathon swim in California Channel Islands history, for swimming so far with a heartfelt appreciation of his crew and a positive mindset and broad smile, and for quietly compiling an impressive list of channel swims in his 50’s, the Two-way Santa Cruz Island Crossing by Ken Mignosa of the USA is a worthy nominee for the 2018 World Open Water Swimming Performance of the Year.

I asked Ken where the nickname “beast” came from. He said: “I earned the nickname in my first year of ultra-marathon swimming, 2017. During that year, I completed the California Triple Crown within 4 months. Each of the swims was plagued with horrible conditions. My Tahoe crossing in July was during a year when there had been phenomenal snowfall. By the time I did my swim, much of the snow was melting, and the end result was that there was a strong current from the snow melt that pushed me away from Incline Village for the last several miles of the swim. My Catalina crossing featured 11 foot swells, high winds and strong currents that almost swept me across San Pedro and down to Long Beach. I recall being at the top of swell, when my pilot vessel was at the bottom of the same swell, and I could easily look down on the deck of the boat and see what was going on there. I also have memories of amazing bioluminescence for the first several hour of the swim. It was a clear night when my swim began, so there were stars above me and glowing life below me. It was pretty magical.

As I said earlier in this note, the Anacapa swim had difficult conditions as well. My “Ken’s Cruz” swim in 2018 began with a swim from Oxnard to Anacapa which took 5 hours. Contrast that with 9 hours for the same swim in 2017.

Some of the folks with whom I train used a phrase that is reserved for folks who persevere through long swims under rotten conditions. They say that the person “beasted out” the swim. During the swims of 2017 I earned the nickname of “the beast” because I persevered through rotten conditions for hours on end in multiple swims. In fact, for awhile there were those at the South End Rowing Club who said that I was a magnet for bad conditions.

This is one of the reasons I consider the English Channel swim so lucky. Instead of bad conditions, for which I had trained, I got smooth water, light currents, and almost no wind. It was almost like a reward for the many swims done with poor conditions . . . ”

” . . .The 20 Bridges swim, also known as the Manhattan Island Marathon Swim, was a fun swim that was actually part of the taper before my Ken’s Cruz swim in 2018. The round trip Santa Cruz island swim was completed less than 2 weeks after swimming around Manhattan. The Manhattan Island Marathon Swim was taken over by a different organizer some years before I completed my swim around Manhattan. Because of concerns about ownership of the name “Manhattan Island Marathon Swim” the swim was renamed 20 Bridges. That’s the number of bridges under which a participant swims. I did backstroke under every bridge so that I could see the bridges. The swim is timed for each swimmer so that it is current assisted. My “speed” going down the Hudson was nearly 7kts. That’s way over world record pace for any pool competition. However, my speed was really really about 2.5kts + 4.5kts ebb current. Still it was pretty neat to go speeding by the the west side of Manhattan.”

Steve Munatones also published a story about my Ken’s Cruz swim at:

http://dailynews.openwaterswimming.com/2018/10/ken-mignosa-goes-long-real-long-in.html

which includes:

Amazingly, Mignosa only began attempting marathon swims in July of 2017 at the age of 53.

“I’d be in [the pool] for an hour or two and I didn’t feel like it was enough,” said Mignosa. He laughs and says that the other downside was having to turn around too soon.

Now Mignosa swims in the San Francisco Bay where he only has to turn around when he’s ready to. Marathon swimmers are not allowed to use a wetsuit in challenges because it adds buoyancy to the swimmer, so Mignosa doesn’t wear one while training.

“Ideally, anything I do for training is colder than what I do for the marathon swim,” said Mignosa. “As long as you keep moving, it tends to be okay.”

as well as a story about my round trip and circumnavigation of Angel Island at:

http://dailynews.openwaterswimming.com/2019/01/back-and-forth-in-bay.html

The 2018 World Open Water Swimming Association (WOWSA) swimming performance of the year was awarded to Ross Edgerton who circumnavigated the UK. I was one of 15 nominees for this honor in 2018 for my Ken’s Cruz swim.

My local paper, the Santa Clara Weekly, published a story about my Ken’s Cruz swim at:

https://www.svvoice.com/santa-clara-mans-passion-for-swimming-takes-him-into-new-waters/

When I saw the mini-video below, I sent Ken an email:

“1,000 dolphins spotted and filmed. Hmmmm, that would make an interesting swim!

https://www.instagram.com/p/CMnffBAAkRu/?utm_source=ig_embed&utm_campaign=loading

and he replied:

“I have swum with a pod like this in the Channel Islands. Or rather a pod like this swam around me. It was cool! Super pods are common in the Santa Barbara Channel. It is the native home to 8 species of dolphins.”