See below for Yosemite year-in-review rockfall reports for the years 2008 – 2025,

and below that see rockfall safety tips from the Wilderness Safety Action Team.

And note that in a report the park service says:

‘ . . . because of the configuration of the steep, tall valley walls and the relatively narrow valley floor, there is no absolutely safe or zero probability areas for rockfalls within Yosemite Valley. The National Park Service must balance the risk to the public from hazards such as rockfalls against the desire of the public to access their national parks…”

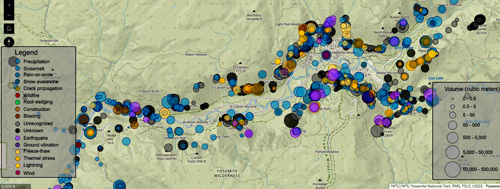

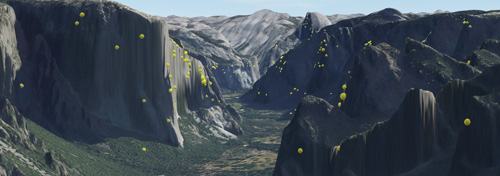

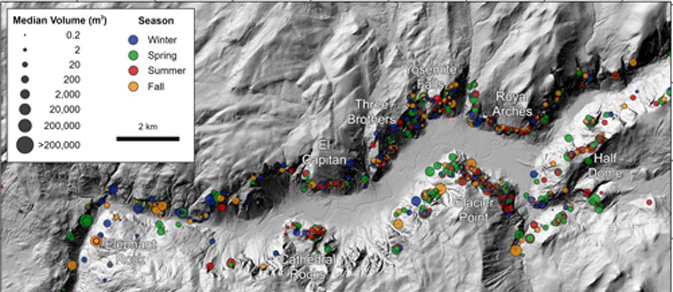

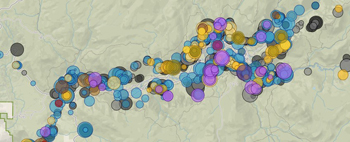

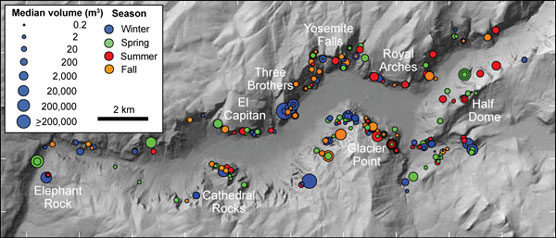

These two maps of Yosemite Valley rockfalls are from the rockfall database.

They show that there have been rockfalls in all of the walls surrounding Yosemite valley.

see full size views at: https://experience.arcgis.com/experience/03e5fb490eaf4bef92494923a99c4fa0/page/2D-Map-of-rock-falls/?dlg=Information

and watch Yosemite Nature Notes on rockfalls

Yosemite Park rockfall page with lots of pictures, links to reading and this map of documented rockfalls in Yosemite valley:

A multitude of photos from the October 2008 rockfalls above Happy Isles that eventually closed 233 Curry Village (Half Dome Village) cabins, etc. and 43 staff housing units can be seen at

https://www.nps.gov/yose/getinvolved/curry_village.htm

See also http://pubs.usgs.gov/ds/746/ Historical Rock Falls in Yosemite National Park, California, 1857-2011

The cover photo is a great one of the October 11, 2010 rock fall and huge cloud of dust rising from the face of El Capitan.

![]()

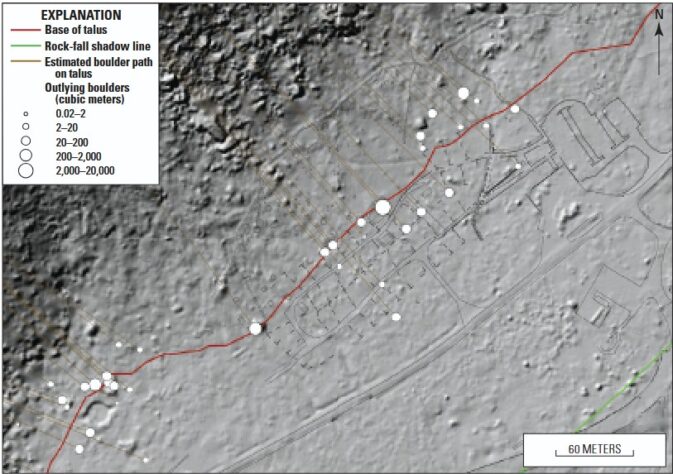

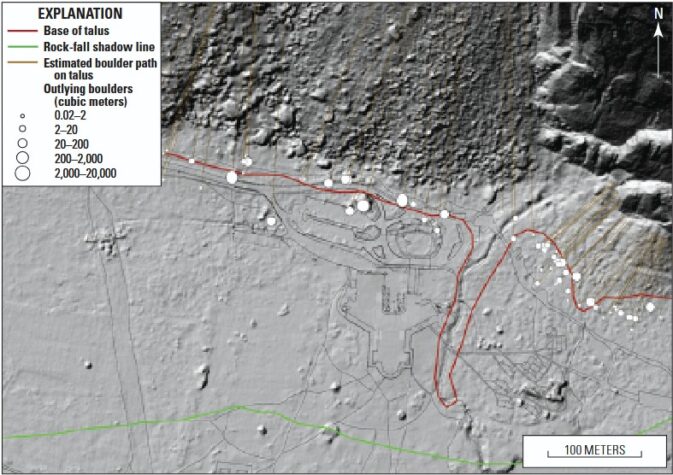

Photos below from USGS Quantitative Rock-Fall Hazard and Risk Assessment

for Yosemite Valley, Yosemite National Park, California https://pubs.usgs.gov/sir/2014/5129/pdf/sir2014-5129.pdf

We read, in that document: “individual, fragmental-type rock falls (herein referred

to simply as “rock falls”) deposit rock debris on talus slopes, with some rock falls depositing “outlying” boulders beyond the edge of talus slopes. Outlying boulder deposition may occur, for example, when boulders have sufficient bouncing or rolling energy such that they do not stop earlier on the talus” outlying boulders ” . . .as large

as approximately 100,000 m3 (cubic meters) in volume”.

Above see outlying boulders (white circles) at part of Camp 4

(Camp 4 includes Columbia Boulder (with the Midnight Lightning route)

See a Google Maps view of Columbia Boulder and scroll slightly to the right to see a person standing near the boulder to get an idea of the size.

Above see outlying boulders (white circles) along the road to the Ahwahnee Hotel, including the Ahwahnee Boulder.

You can also find outlying boulders at the Curry Village, Yosemite Village and more in USGS Quantitative Rock-Fall Hazard and Risk Assessment

for Yosemite Valley, Yosemite National Park, California https://pubs.usgs.gov/sir/2014/5129/pdf/sir2014-5129.pdf

__________________________________________________________

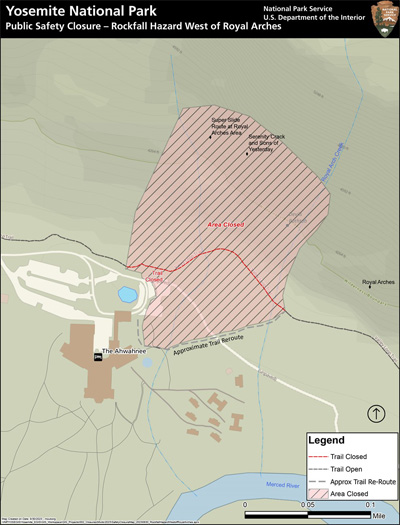

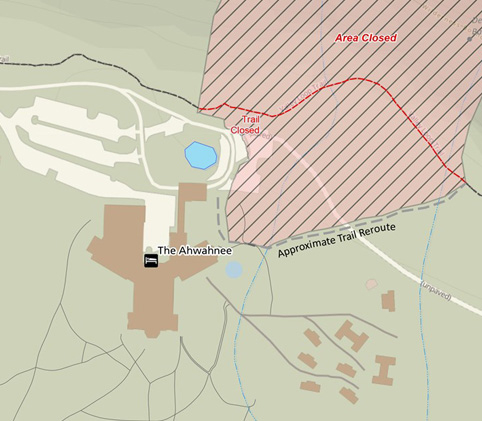

The maps below are from:

Public Safety Closure – Rockfall Hazard West of Royal Arches

August 30, 2023

https://www.nps.gov/yose/learn/management/closures.htm#ahw

The Rockfall Year in Review 2024 (below) gives more details:

“Also of note in 2024 was the continued widening of the crack in the cliff west of Royal Arches and north of the Ahwahnee, adjacent to the climbing route “Super Slide”. This crack was about one inch wide when first discovered in August 2023. Monitoring showed that the crack widened in the fall of 2023, narrowed over the winter of 2023-2024, and then widened again to nearly four inches in August 2024. The crack is being monitored closely, and local closures remain in place.”

This photo of talus below a rockfall from the Rhombus Wall in 2009,

(with an NPS Geologist standing in the lower right hand corner of the photo

and the Ahwahnee Hotel in the upper right) is from a video you can watch:

Yosemite Nature Notes 10: Rock Fall

https://home.nps.gov/media/video/view.htm?id=FD5E8943-046C-4A2E-857ADD5C1E8B71AF

and see the 2009 Rockfall Year in Review below.

![]()

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR

U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY

ROCK FALLS IN YOSEMITE VALLEY, CALIFORNIA

https://pubs.usgs.gov/of/1992/0387/report.pdf

Says of the many quotes from John Muir ”His geomorphic theories and conclusions regarding the glacial and mass movement processes responsible for the formation of Yosemite Valley are still sound.”

It has historical accounts of results of flooding, including

“ . . . Floods may have caused some of the rock-fall effects evident

in early photographs of the valley. A rainstorm that began on January 2, 1862, and continued unabated for 4 days led to flooding of the Merced River that interrupted the attempted travel of James Hutchings to Yosemite. The specific effects of this storm in Yosemite were not directly observed but could well have caused rock falls. During the 1867 flood, Hutchings and his family were the only residents of the valley . . .

“On December 23, 1867, after a snow fall of about three feet, a heavy down-pour of

rain set in, and incessantly continued for ten successive days * * * throughout the

entire Valley * * * each rivulet became a foaming torrent * * * The whole meadow

land of the Valley was covered by a surging and impetuous flood to an average depth

of nine feet Bridges were swept away * * *.

“Immense quantities of talus were washed down upon the Valley during the storm,

more than at any time for scores, if not hundreds, of years * * *.”

![]()

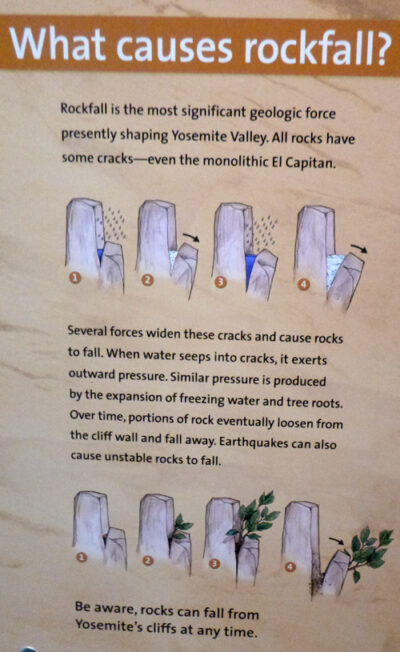

There is an outdoor exhibit on the geologic story of rockfalls in Yosemite at Happy Isles (Yosemite valley free shuttle bus stop #16.

![]()

From a Yosemite visitor center display: What causes Rockfall?

![]()

Notes after a July 5, 2019 earthquake:

“Recent earthquakes and (lack of) rockfalls

Recent earthquakes centered near Ridgecrest, CA, were strongly felt in and around Yosemite Valley. The largest of these, a magnitude 7.1 earthquake at 8:19 pm on July 5, caused shaking of the floor of Yosemite Valley that lasted tens of seconds. Despite this shaking, it seems that there were not any rockfalls triggered by these earthquakes (please let me know if you know otherwise!).

Earthquakes are one of the most reliable rockfall triggers in Yosemite. At 2:30 am on March 26, 1872, John Muir awoke to strong ground shaking, and, stepping outside of his cabin, observed a large rockfall sweeping down the cliff behind the Chapel (he could see it in the dark because of the sparking produced by pulverizing quartz). The Lone Pine earthquake, centered in the southern Owens Valley, was estimated to have been at least magnitude 7.4, and possibly as high as magnitude 7.9. Nine other large rockfalls were triggered by that earthquake, including one from Liberty Cap that generated an airblast that knocked Snow’s Hotel (formerly near the base of Nevada Falls) off of its foundation.

More recently, a series of earthquakes May 25-27, 1980, centered near Mammoth Lakes, CA, triggered many rockfalls in Yosemite Valley. The largest of these, a magnitude 6.3, triggered rockfalls from above the Sierra Point Trail, causing injuries and leading to the permanent closure of that trail.

Given this history of earthquake-triggered rockfalls, why is it that the strong ground shaking last week didn’t trigger rockfalls? The answer likely has to do with the sensitive relationship between earthquake magnitude and epicenter distance. The recent earthquakes were relatively large magnitude, but they were centered 175 miles away from Yosemite Valley, so their energy was greatly attenuated by the time it reached Yosemite. In contrast, the smaller Mammoth Lakes earthquakes were centered just 35 miles from Yosemite Valley, generating strong ground shaking and rockfalls. So although the recent earthquakes were widely felt in Yosemite Valley, the long distance to the epicenter translated into shaking was apparently not strong enough to trigger rockfalls.

Fortunately Yosemite Valley is is a relatively low seismic hazard zone for California, but there are infrequent, large earthquakes along the eastern front of the range that could (will) trigger future rockfalls. If you experience strong ground shaking in Yosemite Valley, move away from the cliffs as quickly as you can. (G Stock)”

________________________________________________________

Read what John Muir wrote about the 1872 earthquake:

https://www.yosemite.ca.us/john_muir_writings/the_earthquake.html

including what Muir said to a fearful neighbor “Come, cheer up; smile a little and clap your hands, now that kind Mother Earth is trotting us on her knee to amuse us and make us good.” .

__________________________________________________________

Grand Canyon National Park has a different perspective:

In https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/rockfalls-and-rain-risk-and-randomness.htm we read:

“Stand in one place and you can pick out hundreds of rocks that are ready to let go and fall into the Grand Canyon. Some are limestone, some are sandstone. Some are mere pebbles, some are the size of apartment buildings. Does one have YOUR name on it?

There is a thunderstorm on the southwest horizon – does it have a lightning bolt meant for you? Will it spawn a flash flood, hidden from view, destined to carry you away in a mud-brown tsunami?

The earth is always moving; ‘solid ground’ is a relative term. “Creep” is the geologic term for slow unnoticed earth movement. Fractures in stone, ever-widening, will eventually cause instability and collapse.

For the visitor standing close to the edge, and even more for the hiker on a trail in the inner canyon, the possibility of a particular rock letting go and falling is always there. But it’s a slim possibility. In a park of 1.2 million acres that receives more than 5 million annual visitors, the chance of your number coming up is far-fetched indeed.

Nevertheless, almost every year someone is tragically hit. You can increase your own safety with alertness. So watch and listen, particularly in monsoon season and in late winter, when most rockfalls take place, due to temperature changes destabilizing the canyon walls. Camp in a safe spot, above flash flood zones but not right below a cliff. Be cognizant that a fire-damaged slope in the rain, trees dead, can turn into a landslide and shove a car off the road. Pay attention to the weather.

Gravity (plus weather and geologic processes) causes rockfall incidents. They are random, unpredictable, and unstoppable. You can only AVOID them. The fact that chances are overwhelming that nothing will happen to you should not cause you to be unaware.

You might have bad luck, but you might also have good luck – that’s life. You may find the best sunset photo, or spy some rare animal, but it’ll never occur if you aren’t looking. The world is random; it’s your job to notice what happens in it. Be alive. Particularly in a natural environment like a national park, one is subject to an element of risk. Deep in the canyon, the EMTs and the ambulances are far away.

Treasure that feeling. It’s the way the world was for our ancestors until recently. We are ‘spoiled’ now by the safety and health infrastructure, able to avoid most pain and suffering. We live in the safest 50 years of world history (despite what you may hear in the news).

Some people need a certain amount of risk to feel alive. Others of us won’t drive across a bridge. Some of us need all the answers, religious and political, to be secure. Some of us need all the money. Security, though, is a matter of degrees, never an absolute, and ‘insecurity’ is just the absence of protection. Welcome to the real world.”

All of these Rockfall Year in Review reports are from the Yosemite Daily Report :

_______________________

2025 Yosemite Rockfall Year in Review

2025 was a quiet year for rockfalls in Yosemite, with 43 documented events with a cumulative volume of approximately 478 cubic meters (1,423 tons). Both numbers, and particularly the cumulative volume, are below 20-year averages. As is typical, most of the documented rockfalls in 2025 consisted of relatively small rocks that fell onto park roadways during winter storms.

The two largest rockfalls in 2025 impacted park trails, though fortunately both occurred at night when there were no hikers. The first and largest rockfall occurred at 9:30 pm on March 31, when visitors in Curry Village heard a rumbling sound from the vicinity of Grizzly Peak. The first hikers on the Mist Trail the following morning encountered large boulders blocking the trail on the north side of the Vernal Fall footbridge. Approximately 150 cubic meters (446 tons) of rock had fallen from a point 385 m (1,270 feet) above the trail on the south side of Grizzly Peak, the same location as a similarly sized rockfall on February 5, 2024. That portion of trail was closed for several weeks as a trail crew blasted and cleared the boulders.

The second, smaller rockfall occurred at 1:25 am on May 8. Residents in Yosemite Village again heard rumbling in the night, and the following morning hikers on the Upper Yosemite Falls Trail encountered fresh rock debris on the traversing section of the trail between Columbia Point and the base of the Upper Falls. Approximately 80 cubic meters (238 tons) of rock had slid out from beneath an overhang, tumbling 55 m (180 feet) to the trail. The trail was briefly closed for assessment and initial debris clearing.

Other significant rockfalls in 2025 occurred from Glacier Point, Cathedral Rock, El Capitan, and the Snow Creek Trail.

If you witness a rockfall of any size or encounter fresh rock debris, please contact park geologist Greg Stock at 209/768-1028 or by email at greg_stock@nps.gov, or contact Park Dispatch by dialing 911 within the park.

Documented rockfalls are added to the park database https://experience.arcgis.com/experience/03e5fb490eaf4bef92494923a99c4fa0/ enabling long-term evaluation of rockfall activity to improve public safety. (G. Stock)

_______________________

2024 Yosemite Rockfall Year in Review

2024 was a relatively quiet year for rockfalls in Yosemite, with 42 documented rockfalls and a cumulative volume of 1,397 cubic meters (4,158 tons), both are which are below 20-year averages. Although there wasn’t an obvious “standout” rockfall in 2024, several deserve mention.

The largest rockfall of 2024 occurred at 10:23 pm on April 15. Visitors sleeping in the Pines campgrounds were awoken by distant thundering sounds indicative of a rock fall, but the location was unclear. Three days later a Wilderness Ranger hiking the seasonally closed section of the John Muir Trail between Nevada Fall and Clark’s Point encountered literal tons of rock debris on the trail. Approximately 562 cubic meters (1,672 tons) of rock slid from just below the south rim of the canyon, fragmenting into boulders that tumbled across three switchbacks. Hundreds of boulders came to rest on the trail, two areas of trail sustained deep impact craters, and several fir trees were snapped or toppled by rock impacts. Although the weather was clear at the time, water was observed seeping from the source area, suggesting a snowmelt trigger. The trail was closed for several weeks as boulders were drilled, blasted, and cleared.

Rockfalls alter Yosemite’s landscape, sometimes dramatically. At 11:20 am on May 14, a small rockfall occurred from LeConte Gully below Glacier Point, sending boulders down the path of Staircase Falls. The rockfall originated from a narrow granite fin forming the east wall of LeConte Gully that was the source of rockfalls in 2003 and 2007. https://nhess.copernicus.org/articles/8/421/2008/nhess-8-421-2008.pdf Part of the fin collapsed, allowing Staircase Creek a more direct path over the cliff, instantly forming a new 150-foot-tall waterfall at the top of Staircase Falls.

Two rockfalls affected the Upper Yosemite Falls Trail in 2024. The first occurred at 7:14 am on October 11, when approximately 28 cubic meters (84 tons) of rock fell from the cliff above the traversing section of the trail between Columbia Point and the base of the Upper Falls. Boulders swept across the trail and fell into the Lower Falls Amphitheater below. Fortunately, the early morning timing meant that both that section of trail and the amphitheater were devoid of people. The second rockfall occurred at 2:58 pm on December 26. Approximately 33 cubic meters (98 tons) of rock fell from high on the “Forbidden Wall” above the upper switchbacks, with rock debris tumbling over 20 switchbacks of the trail. One visitor sustained leg injuries but was able to walk out with assistance. In both cases, the trail was closed pending geological assessment.

Other significant rockfalls in 2024 occurred from Grizzly Peak, Castle Cliffs, Sentinel Creek, and the Big Oak Flat Road.

Also of note in 2024 was the continued widening of the crack in the cliff west of Royal Arches and north of the Ahwahnee, adjacent to the climbing route “Super Slide”. This crack was about one inch wide when first discovered in August 2023. Monitoring showed that the crack widened in the fall of 2023, narrowed over the winter of 2023-2024, and then widened again to nearly four inches in August 2024. The crack is being monitored closely, and local closures remain in place.

If you witness a rockfall of any size or encounter fresh rock debris, please contact park geologist Greg Stock at 209/768-1028 or by email at greg_stock@nps.gov, or contact Park Dispatch by dialing 911 within the park. Documented rockfalls are added to the park database, https://experience.arcgis.com/experience/03e5fb490eaf4bef92494923a99c4fa0/ enabling long-term evaluation of rockfall activity to improve public safety. (G. Stock)

_______________________

Yosemite Rockfall Year in Review 2023

2023 was a very active year for rockfalls in Yosemite, with a large number of rockfalls and debris flows, as well as unusual events not seen in more typical years. The winter of 2022-2023 was very wet and cold, with low snow levels. As a result, wintertime rockfall activity was higher than normal and skewed toward lower elevations where rain dominated. Roads were closed on multiple occasions, with 35 rockfalls and debris flows affecting the El Portal, Big Oak Flat, and Wawona roads.

Intense rain and saturated soils produced many debris flows. At 9 pm on January 9, a landslide originating from the canyon wall above Old El Portal quickly mobilized into a debris flow down a steep gully. Before the debris flow reached Old El Portal it was intercepted by a catch basin installed in the mid-1990s, trapping the debris and protecting structures downslope. With the catch basin full and the slope above still susceptible to landslides, an evacuation advisory was put in place during subsequent storms. On March 10, a rain-on-snow event in Yosemite Valley triggered wet snow avalanches that mobilized into debris flows near Yosemite Lodge and the NPS stables. Four days later, heavy rain triggered debris flows that buried the El Portal Road near Arch Rock and deposited boulders into the Merced River opposite Dog Rock. March 14 set a record for the greatest number of rockfalls and debris flows documented in a single day (15).

The most spectacular rockfall of 2023 occurred at 11:41 am on February 20 from the southeast face El Capitan. A single block of 1,595 cubic meters (4,746 tons) fell from the cliff along the path of Horsetail Fall, free-falling 325 meters (1,060 feet) before impacting the base of the cliff. Small rocks landed on Northside Drive, but fortunately the road was closed for the Horsetail Fall viewing event and there were no injuries. The Horsetail Fall viewing area was closed while geologists assessed the hazard.

Other large rockfalls in 2023 occurred at Glacier Point, LeConte Gully, Ahwiyah Point, and Snow Creek. In all, there were 72 rockfalls documented in 2023, with a cumulative volume of 18,730 cubic meters (55,740 tons), well above annual averages.

Two additional events in 2023 are worth mentioning. The first is a crack that appeared in the John Muir Trail between Clark Point and Nevada Fall in mid-May. The second is a crack that formed in the cliff west of Royal Arches and north of the Ahwahnee, adjacent to the climbing route “Super Slide”; this crack was first discovered in late August and continued to grow into September. Both new cracks have partially detached large rock slabs and are being closely monitored.

If you witness a rockfall of any size or encounter fresh rock debris, please contact park geologist Greg Stock at 209/768-1028 or by email at greg_stock@nps.gov, or contact Park Dispatch by dialing 911 within the park. Documented rockfalls are added to the park database (https://experience.arcgis.com/experience/03e5fb490eaf4bef92494923a99c4fa0/), enabling long-term evaluation of rockfall activity to improve public safety. (G. Stock)

Below is an example of a map at the park database mentioned in the report above, of the sizes of rockfalls in Yosemite valley and their causes (snowmelt, precipitation, earthquake, lightning, freeze/thaw, root wedging and more).

Winter Rockfall Update (to March 30, 2023)

For the winter storm period of 2022-2023 (October 1 to March 30), there were 69 documented rockfalls, rockslides, and debris flows, with a cumulative volume of about 19,000 cubic meters. These events resulted in two fatalities on the El Portal Road, two evacuation advisories for parts of Old El Portal, a 24-hour closure of the Horsetail Fall viewing area, and 18 instances of road closure. Although rockfall consequences were unusually high this winter, frequency/magnitude numbers are on par with previous wet winters – the same period in 2016-2017 had a roughly similar number of events (60) with an even larger cumulative volume (about 25,000 cubic meters). (G. Stock)

_______________________________________________________________

Yosemite Rockfall Year in Review: 2022

2022 proved to be an active year for rockfalls and other slope movements in Yosemite, particularly along lower elevation roadways. Although there weren’t any especially large-volume rockfalls in 2022, the year was a reminder that even relatively small rockfalls can be highly consequential.

The first significant rockfall occurred at 2:37 pm on May 15, originating from just below Union Point. A rock outcrop at the top of the slope there slid over a cliff, breaking into boulders that tumbled down a gully, crossing nine switchbacks of the Four Mile Trail before falling to the valley floor. Two visitors hiking the trail were hit by rocks, sustaining minor injuries.

Rockfall activity increased in the fall as storms swept across Yosemite. The Big Oak Flat Road was damaged by a rockfall on the evening of November 8, and again by a larger rockfall on the early morning of December 12; in both cases the road was closed for a few days while rocks were removed and the road repaired.

The largest rockfall of 2022 originated from midway up Middle Brother on the evening of November 12. A slab of rock of about 1,344 cubic meters in volume (about 4,000 tons) detached from the face, hitting a ledge; that impact then dislodged another 158 cubic meters (446 tons) from two other points lower on the cliff. Most of the resulting rock debris was deposited on the talus slope below the cliff, but some boulders bounced over Northside Drive, causing minor road damage.

The most consequential rockfall of 2022 occurred at 9 am on December 27. About 60 cubic meters (about 180 tons) of rock fell from the north rim of the canyon east of the Arch Rock Entrance Station, fragmenting into dozens of boulders that tumbled down to the El Portal Road. A vehicle traveling toward Yosemite Valley was struck by a boulder, tragically killing the two occupants.

The final days of 2022 corresponded with another period of heavy rain, resulting in at least 15 rockfalls and debris slides within a 24-hour period that again affected park roads.

Other substantial rockfalls in 2022 occurred from El Capitan, Half Dome, near Pulpit Rock, and in the Grand Canyon of the Tuolumne. In all, there were 52 rockfalls documented in 2022, with a cumulative volume of about 2,100 cubic meters (6,250 tons).

If you witness a rockfall of any size or encounter fresh rock debris, please contact park geologist Greg Stock at 209/768-1028 or by email at greg_stock@nps.gov, or contact Park Dispatch by dialing 911 within the park. Documented rockfalls are added to the park database (in new interactive map form here https://experience.arcgis.com/experience/03e5fb490eaf4bef92494923a99c4fa0/), enabling long-term evaluation of rockfall activity to improve public safety. (G. Stock)

_______________________

Yosemite Rockfall Year in Review: 2021

2021 proved to be a relatively mild year for rockfalls and other slope movements in Yosemite. Forty-seven rockfalls were documented in 2021, with a cumulative volume of about 1,570 cubic meters (4,670 tons). Both metrics are below recent averages, perhaps related to below-average precipitation in 2021.

The two largest rockfalls in 2021 occurred at El Capitan. The largest was an approximately 1,000 cubic meter (nearly 3,000 ton) slab that fell from low on the west face; this event was not directly observed but likely happened during intense rain in October. The other, a 55 cubic meter (160 ton) slab, fell from the southeast face on the afternoon of November 16.

Other substantial rockfalls in 2021 occurred from Parkline Slab, Sentinel Rock, Sunnyside Bench, Glacier Point, Porcelain Wall, and Royal Arches.

The most consequential event of 2021 was a series of debris flows (water-laden sediment flows) that damaged portions of the John Muir and Mist trails. At 4 pm on June 30 a localized thunderstorm dropped heavy rain over eastern Yosemite Valley, triggering several debris flows between Happy Isles and Vernal Fall. The largest debris flow cut a 2-meter-deep gully through the John Muir Trail, depositing about 50 cubic meters (150 tons) of sand, gravel, and boulders onto the Mist Trail below. Smaller debris flows totaling about 30 cubic meters (90 tons) damaged the stock trail between Happy Isles and the Vernal Fall footbridge.

If you witness a rockfall of any size, encounter fresh rock debris, or hear cracking or popping sounds emanating from the cliffs, please contact park geologist Greg Stock at 379-1420 or greg_stock@nps.gov, or contact Park Dispatch by dialing 911 within the park. Documented rockfalls are added to the park database (http://pubs.usgs.gov/ds/746/), enabling long-term evaluation of rockfall activity to improve public safety. (G. Stock)

_______________________

Yosemite Rockfall Year in Review: 2020

2020 proved to be a relatively mild year for rockfalls in Yosemite. Thirty-four rockfalls were documented in 2020, with a cumulative volume of about 3,120 cubic meters (9,285 tons). Both metrics are well below recent averages. The lower numbers may be due in part to below-average precipitation in 2020 (rainfall is a common rockfall trigger) but they more likely result from under-reporting. COVID-19 related access restrictions throughout most of 2020 meant that there were fewer people present to witness and report rockfalls.

The two largest rockfalls of 2020 happened in the summer. The first occurred at 7:14 pm on June 20, when a large exfoliation slab fell from the “Porcelain Wall” just west of Half Dome. Hundreds of park visitors around Mirror Lake watched as the slab, about 1,040 cubic meters in volume (nearly 3,100 tons), toppled from the wall and impacted a ledge below, exploding into thousands of fragments and generating a large dust cloud that filled Tenaya Canyon. Although spectacular, the rockfall was fortunately not consequential, as rock debris did not make it as far down as the Mirror Lake loop trail.

Another large rockfall occurred just two weeks later, when about 940 cubic meters (2,80 tons) of rock fell from low on Middle Brother at 8:42 am on July 4. Again, the rockfall was witnessed by hundreds of visitors enjoying the holiday. The rockfall created a dust cloud but did not damage infrastructure in the area. Four smaller rockfalls occurred from the same location later that night. This location has been intermittently active since 2016, demonstrating a progressive pattern that is relatively common in Yosemite. The Porcelain Wall and Middle Brother rockfalls both occurred on hot days, suggesting that heat may have triggered the rockfalls by thermal expansion of partially detached exfoliation slabs.

Other substantial rockfalls in 2020 occurred from El Capitan, Yosemite Falls, Glacier Point, and the Cascade Cliffs above Little Yosemite Valley.

If you witness a rockfall of any size, encounter fresh rock debris, or hear cracking or popping sounds emanating from the cliffs, please contact park geologist Greg Stock at 209/379-1420 or by email at greg_stock@nps.gov, or contact Park Dispatch by dialing 911 within the park. Documented rockfalls are added to the park database (http://pubs.usgs.gov/ds/746/), enabling long-term evaluation of rockfall activity to improve public safety. (G. Stock)

_______________________

Yosemite Rockfall Year in Review: 2019

“2019 proved to be a relatively benign year for rockfalls in Yosemite. Despite anxiety about elevated rockfall and debris flow potential in the Ferguson Fire burn scar, abundant snow and generally low-intensity rainfall limited the activity to a few small slides, mostly on the Wawona Road. Sixty-four events (including rockfalls, rockslides, and debris flows) were documented in 2019, with a cumulative volume of about 2,630 cubic meters (7,830 tons).

The largest and most consequential rockfall of 2019 occurred on February 4 at 9:20 am, just after heavy snowfall. Two blocks totaling about 420 cubic meters (1,250 tons) fell in quick succession from midway up the north face of Sentinel Rock, sliding over a ledge and pummeling the base of the cliff. Boulders tumbled across the Four Mile Trail, damaging the power line below and causing a prolonged power outage at Glacier Point.

The second largest rockfall of 2019 occurred from the Panorama Cliff near Happy Isles at 7:15 pm on September 22, when about 300 cubic meters (810 tons) of rock fell from low on the cliff. The rockfall created a dust cloud but did not affect any infrastructure.

The most consequential rockfall for me personally occurred on December 5. On that day, a friend and I were conducting field work at the base of the southeast face of El Capitan, near the start of the route “Zodiac”. The wall is overhanging there. At 12:48 pm we heard a scraping sound high above us, followed by the sound of a large object rushing through the air. As this sound increased to deafening levels, we ran to the wall and crouched behind a boulder just as a 15 cubic meter (45 ton) rock exploded near us, pelting us with small rock fragments. A golf ball-sized fragment struck my helmet, but we emerged from the dust unscathed. This event reminded me that situational awareness – being vigilant and having a plan for where to shelter in case of rockfall – is essential in rockfall-prone areas. Helmets also help!

Other substantial rockfalls in 2019 occurred in the Merced River Gorge, Glacier Point, Indian Canyon, and the Camp 4 Wall.

It is very likely that there were additional rockfalls and rockslides in 2019, but these events either were not witnessed or went unreported. If you witness a rockfall of any size, encounter fresh rock debris, or hear cracking or popping sounds emanating from the cliffs, please contact park geologist Greg Stock at 209-379-1420 or by email at greg_stock@nps.gov, or contact Park Dispatch by dialing 911 within the park. Documented rockfalls are added to the park database (http://pubs.usgs.gov/ds/746/), enabling long-term evaluation of rockfalls to improve public safety. (G. Stock)”

_______________________

Yosemite Rockfall Year in Review: 2018

“Yosemite faced a number of challenging events in 2018, including floods and fires, but fortunately serious rockfalls were not among them. Forty-one events (including rockfalls, rockslides, and debris flows) were documented in 2018, below the recent (2006-2017) average of 53 events per year, and less than half of that documented in 2017. Rockfalls in 2018 had a cumulative volume of about 2,220 cubic meters (6,610 tons), also well below the recent average of 10,068 cubic meters (about 30,000 tons).

The largest rockfall of 2018 was not in Yosemite Valley, but instead occurred deep within the Grand Canyon of the Tuolumne, between Muir Gorge and Pate Valley. It likely occurred sometime in March with the first real winter storms, but it wasn’t reported until the trail was accessible in early summer. Approximately 1,500 cubic meters (4,465 tons) of rock slid off the north wall of the canyon, spreading out over the canyon bottom and burying the trail under large boulders and trees. Clearing the trail of this debris was a summertime priority for trail crews.

The most consequential rockfall of 2018 was a relatively small rockfall from the northwest face of Half Dome. On the morning of June 5, a thin exfoliation slab of about 5 cubic meters (15 tons) fell from the east side of the face, breaking into hundreds of fragments that funneled down a steep gully containing the lower pitches of the Regular Northwest Face climbing route. The debris struck a climbing party on the third pitch, causing a neck laceration and possible dislocated shoulder. The climber’s helmets sustained significant damage, suggesting, once again, that wearing helmets probably saved lives. The injured climbers rappelled to the base of the route and were evacuated by helicopter.

Other substantial rockfalls in 2018 occurred at Parkline, El Capitan, Indian Canyon, the south face of Half Dome, and Quarter Domes.

It is very likely that there were additional rockfalls and rockslides in 2018, but these events either were not witnessed or went unreported. If you witness a rockfall of any size, encounter fresh rock debris, or hear cracking or popping sounds emanating from the cliffs, please contact park geologist Greg Stock at 209/379-1420 or by email at greg_stock@nps.gov, or contact Park Dispatch by dialing 911 within the park. Documented rockfalls are added to the park database (http://pubs.usgs.gov/ds/746/), enabling long-term evaluation of rockfall activity to improve public safety. (G. Stock)”

_______________________

Yosemite Rockfall Year in Review: 2017

“There many large and consequential rockfalls in Yosemite in 2017, with a record 85 events (including rockfalls, rockslides, and debris flows) documented. The cumulative volume of these events was about 36,800 cubic meters. Although this is not the largest annual volume recorded, greater volumes in previous years were typically dominated by one very large event (for example, the 46,700 cubic meter rockfall from Ahwiyah Point in 2009), whereas the cumulative volume for 2017 resulted from several large and medium-sized rockfalls.

The largest event in 2017 almost escaped notice. On the stormy morning of January 12, road crews encountered downed trees and a damaged manhole on the road between Pohono Bridge and the Big Oak Flat Road junction. They also noticed a suspiciously fresh-looking boulder in the Merced River. Subsequent investigation revealed that the boulder was part of a very large rockslide that originated far above the road in an area known (appropriately) as “The Rockslides”. The total volume of this slide was about 20,000 cubic meters (almost 60,000 tons), most of which was scattered throughout the forested slopes above the road. If not for the single boulder that hit the road, this rockslide might have escaped notice for some time.

Much greater road damage occurred on June 12, when about 650 cubic meters (nearly 2,000 tons) of rock fell from “Parkline Slab”, a sloping cliff just east of the park boundary near El Portal. About one-third of the rock debris landed on the El Portal Road, burying a 60 meter (200 foot)-long section of road under tons of rock; fortunately, there were no cars directly under this area, despite the rockfall occurring around noon during the busy summer season. The road was closed for five days as crews cleared debris and repaired the roadbed. Much loose debris remains on the slope above the road, and could continue to slide during intense rainstorms.

The year’s most consequential rockfalls occurred from the southeast face of El Capitan in September. The first of these occurred at 1:52 pm on September 27, when 290 cubic meters (860 tons) of rock fell from the cliff near the path of Horsetail Fall. Two rock climbers were walking along the base of the cliff directly under the area, and, sadly, one of them was killed and the other seriously injured. YOSAR quickly extracted both climbers, as several more rockfalls totaling 163 cubic meters (440 tons) pummeled the base of the cliff over the next few hours. At 3:21 pm the following day (September 28), a much larger rockfall occurred from the same location. This rockfall, totaling 10,324 cubic meters (27,875 tons), buried trees at the base of the cliff and generated a huge dust cloud that fanned out across the valley. A small rock fragment hit a vehicle traveling on Northside Drive, puncturing the sunroof and injuring the driver. Northside Drive was closed for 24 hours as geologists assessed the potential for additional activity. Several smaller rockfalls occurred from this same area in October and November.

Other substantial rockfalls in 2017 occurred at Little Windy Point on the El Portal Road, Ahwiyah Point, Glacier Point, El Capitan, Middle Cathedral Rock, and Hetch Hetchy.

It is very likely that there were additional rockfalls and rockslides in 2017, but these events either were not witnessed or went unreported. If you witness a rockfall of any size, encounter fresh rock debris, or hear cracking or popping sounds emanating from the cliffs, please contact park geologist Greg Stock at 209-379-1420 or greg_stock@nps.gov, or contact Park Dispatch by dialing 911 within the park. Documented rockfalls are added to the park database (http://pubs.usgs.gov/ds/746/), enabling long-term evaluation of rockfall activity to improve public safety. (G. Stock)”

______________________________________________________________

“Another Rockfall in Yosemite National Park – Yosemite News Release

September 28, 2017, 6:30pm

Rockfall in same area on El Capitan, but significantly larger

Another rockfall occurred on the Southeast face of El Capitan in Yosemite National Park this afternoon at 3:21 p.m. The rockfall is significantly larger than yesterday’s rockfalls. Geologists are assessing the size and weight of the rockfall and these estimates are forthcoming.

There was an injury associated with today’s rockfall event. The injured person was flown out of the park via air ambulance to receive medical care at an area hospital.

Rockfalls are a common occurrence in Yosemite Valley and the park records about 80 rockfalls per year; though many more rockfalls go unreported. The rockfall from El Capitan was similar in size and extent compared with other rockfalls throughout the park, though it is not typical that that there were victims.

The victim of yesterday’s rockfall at 1:52 p,m. has been identified as Andrew Foster of Wales. He was 32 years old. His wife is undergoing medical treatment in an area hospital.

Roads within Yosemite Valley have been rerouted and the changes will be in effect at least through tomorrow. All roads remain open in Yosemite National Park.

Yosemite National Park remains open and visitor services are not affected by the rockfalls over the past couple of days. (S. Gediman)”

_______________________________________________________________

“Additional Information On Rockfall In Yosemite National Park – Yosemite News Release September 28, 2017, 10:30 a.m.

One fatality, one injury, and all people accounted for

A series of rockfalls occurred yesterday afternoon from the Southeast face of El Capitan in Yosemite National Park. Seven rockfalls occurred over a four-hour time span, with the initial rockfall happening at 1:52 P.M. Pacific Daylight Time.

A preliminary estimate for the cumulative volume of all seven rockfalls is about 16,000 cubic feet (450 cubic meters), or about 1,300 tons. The irregular “sheet” of rock that fell is estimated to be 130 feet tall, 65 feet wide, and 3-10 feet thick. The source point is about 650 feet above the base of El Capitan, or about 1,800 feet above the floor of Yosemite Valley (which is at 4,000 feet in elevation).

After the initial rockfall, Yosemite National Park Rangers and the Search and Rescue team entered the area looking for people at the base of the rockfall. Two people were found, resulting in one fatality and a serious injury. The victims, a couple visiting the park from Great Britain, were in the park to rock climb but were not climbing at the time of the initial rockfall. The male was found deceased and the female was flown out of the park with serious injuries. The National Park Service is working with the Consulate to notify family members. Until family notifications are completed, the names of the victims are not being released. All other people in the area have been accounted for and search efforts have been concluded.

Rockfalls are a common occurrence in Yosemite Valley and the park records about 80 rockfalls per year; though many more rockfalls go unreported. The rockfall from El Capitan was similar in size and extent compared with other rockfalls throughout the park, though it is not typical that that there were victims.

It has been 18 years since the last rockfall-related fatality in Yosemite National Park. In that incident, rock climber Peter Terbush was killed by a rockfall from Glacier Point June 13 1999. There have now been 16 fatalities and more than 100 injuries from rockfalls since park records began in 1857.

Yosemite National Park remains open and visitor services are not affected by the rockfalls. (S. Gediman)”

__________________________________________________________________________

“Rockfall In Yosemite National Park – Yosemite News Release September 27, 2017 4:30 p.m.

A rockfall of undetermined size occurred in Yosemite National Park this afternoon at about 1:55 p.m. this afternoon. The rockfall was reported to have happened from El Capitan, a granite monolith above Yosemite Valley. The release point appears to be near the “Waterfall Route”, a popular climbing route on the East Buttress of El Capitan. This is the area where Horsetail Fall flows in winter and spring conditions. . . ”

_______________________________________________________________________

“Yosemite Rockfall Year in Review: 2016

Rockfall activity in 2016 was slightly lower than in previous years, with 58 documented events (rockfalls and rockslides) and a cumulative volume of about 5,000 cubic meters (roughly 15,000 tons). Nevertheless, many of these rockfalls were consequential, impacting park infrastructure and affecting park visitors, employees, and residents.

The year got off to a quick start with a rockfall on January 9 from “Little Windy Point” near Dog Rock. Roughly 90 cubic meters (270 tons) of rock slid onto the El Portal Road, blocking both lanes. The road was closed for several days as the cliff was assessed and the road cleared. (Note: this same location was active again almost exactly one year later.)

Later in the year, another larger rockfall in the Merced River Gorge impacted the El Portal Road on the rainy afternoon of October 31 (Halloween). A huge boulder (approximately 1,000 cubic meters, or nearly 3,000 tons) perched on the canyon rim above and west of Kat Pinnacle slid out along saturated soil and tumbled down the slope toward the river. Fortunately the boulder stopped against a bedrock outcrop midway down the slope, but another 80 cubic meters of associated rock debris landed on the road. The road was closed for a day as the rocks were blasted and cleared.

The most interesting rockfalls of 2016 happened at Middle Brother. Reminiscent of the 2009-2010 rockfalls from the Rhombus Wall, a series of rockfalls occurred from the lower part of the Middle Brother cliff over several months. The first occurred sometime in early February, as a roughly 1,000 cubic meter (3,000 ton) slab of rock exfoliated from the cliff, decimating the live oak forest at the base of the cliff and sending large boulders to the edge of the talus slope near Wahhoga. Smaller slabs fell sporadically throughout the spring and summer. On the afternoon August 3, hundreds of park visitors witnessed two large rockfalls in quick succession that produced large dust clouds. Another rockfall occurred on August 4, and four more occurred on August 5. In all, some 2,000 cubic meters (nearly 6,000 tons) of rock were shed from the cliff in 2016. This “progressive” rockfall behavior is occasionally displayed in exfoliating landscapes and is an area of vigorous scientific research.

Other substantial rockfalls in 2016 occurred from Sunnyside Bench, the East Ledges of El Capitan, Panorama Cliff, Little Yosemite Valley, the Merced River Gorge, and Hetch Hetchy.

It is very likely that there were additional rockfalls and rockslides in 2016, but these events either were not witnessed or went unreported. If you witness a rockfall of any size, encounter fresh rock debris, or hear cracking or popping sounds emanating from the cliffs, please contact park geologist Greg Stock at 209/379-1420 or by email at greg_stock@nps.gov, or contact Park Dispatch by dialing 911 within the park. Documented rockfalls are added to the park database (http://pubs.usgs.gov/ds/746/), enabling long-term evaluation of rockfall activity to improve public safety. (G. Stock)”

_______________________________________________________________________

Yosemite Rockfall Year in Review: 2015

“Despite a fourth consecutive year of drought, rockfall activity in 2015 was about average, with 66 documented events (rockfalls, rockslides, and debris flows). The cumulative volume of all events was about 8,700 cubic meters (roughly 25,000 tons).

Surprisingly, the largest and most notable rockfall of 2015 was not directly observed. On July 5, two rock climbers attempting the Northwest Face of Half Dome found themselves stymied by a new expanse of blank rock. Sometime in the previous days a rock slab totaling some 1,800 cubic meters (about 5,200 tons) parted from the cliff in a classic case of exfoliation, taking with it two pitches of one of the world’s most famous climbing routes. Although the rockfall happened at the height of the summer tourist season – and also the Half Dome climbing season – the stormy weather that apparently triggered the rockfall ensured that no one was in the immediate vicinity to witness the event. Another rockfall from Half Dome on July 15 originated from a different location near “The Visor” and was apparently unrelated to the earlier event.

Other substantial rockfalls in 2015 occurred from Middle Brother west of Camp Four, Washington Column, Clouds Rest, Glacier Point, and the north wall of Hetch Hetchy Valley.

In a notable departure from past years, more than half (54%) of the cumulative volume for 2015 was related to debris flows triggered by intense rainstorms. In particular, two thunderstorms in July and October – the former a remnant of Hurricane Dolores – generated substantial runoff and debris from within the burned areas of the Dog Rock and El Portal fires. The El Portal Road was closed for three days as debris from the July event was cleared from the road. Although burned areas proved susceptible to debris flows, unburned areas also experienced large debris flows, indicating that localized weather plays the primary role in triggering these events.

It is very likely that there were additional rockfalls, rockslides, and debris flows in 2015, but these events either were not witnessed or went unreported. If you witness a rockfall of any size, encounter fresh rock debris, or hear cracking or popping sounds emanating from the cliffs, please contact park geologist Greg Stock at 209/379-1420 or by email at greg_stock@nps.gov, or contact Park Dispatch by dialing 911 within the park. Documented rockfalls are added to the park database (http://pubs.usgs.gov/ds/746/), enabling long-term evaluation of rockfall activity to improve public safety. (G. Stock)”

_______________________________________________________________________

Yosemite Rockfall Year in Review: 2014

“Despite near-record dry conditions, 2014 was an active year for rockfalls in Yosemite. In all, there were 77 documented rockfalls, which is considerably more than the recent (2006-2013) average of about 45 rockfalls per year. Most of the rockfalls in 2014 were relatively small, with a total volume of about 6,500 cubic meters (about 19,350 tons).

The largest rockfall of 2014 occurred at 1:30 pm on March 31 from the north wall of Hetch Hetchy valley near Wapama Falls. This rockfall had a volume of roughly 5,000 cubic meters (about 14,880 tons). Rock debris buried a 120 meter-long section of the Rancheria Trail along the north shore of the reservoir, necessitating a multi-week closure while the trail was rebuilt. The second largest rockfall of 2014 occurred at about 4:30 am on the morning of June 11, when a 450 cubic meter (1340 tons) block fell from the southeast face of El Capitan near Horsetail Falls. The block fragmented on impact, creating a large dust cloud that lingered in western Yosemite Valley for more than an hour.

The most consequential rockfall of 2014 occurred at 8:15 pm on June 29, when a rock slab of about 215 cubic meters (about 640 tons) fell from the east wall of Indian Canyon. Although nobody was in this remote area at the time, a segment of the communications cable running up Indian Canyon was destroyed, cutting off all phone communications to White Wolf and Tuolumne Meadows. The cable was replaced by a microwave transmitter.

Perhaps the most important rockfall of 2014 was also one of the smallest. At 3:22 am on the morning of February 11, a rockfall of approximately 15 cubic meters (about 45 tons) occurred in the vicinity of Staircase Falls above Curry Village. Previous rockfalls in 2003 and 2007 damaged cabins, caused injuries, and prompted evacuations. In contrast, the February 11, 2014 rockfall was hardly noticed because cabins there were removed in late 2013 following a comprehensive assessment of rockfall hazard and risk (http://pubs.usgs.gov/sir/2014/5129/). One boulder landed within the footprint of a former cabin. This event, described in a short publication, (http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/2014EO290002/pdf), demonstrated the merit of removing buildings from hazardous areas.

Other areas in Yosemite experiencing rockfalls in 2014 include Yosemite Falls, Royal Arches, LeConte Gully, and the Merced River Gorge; these latter rockfalls were related to the Dog Rock Fire in early October.

It is very likely that there were additional rockfalls in 2014, but these events either were not witnessed or went unreported. However, the significant increase in the number of small rockfalls in 2014 suggests more thorough reporting of rockfalls (and likely not a real increase in small rockfalls). If you witness a rockfall of any size, encounter fresh rock debris, or hear cracking or popping sounds emanating from the cliffs, please contact park geologist Greg Stock at 209/379-1420 or by email at greg_stock@nps.gov, or contact Park Dispatch by dialing 911 within the park. Documented rockfalls are added to the park database (http://pubs.usgs.gov/ds/746/), enabling evaluation of rockfall activity to improve public safety. (G. Stock)”

_______________________________________________________________________

Yosemite Rockfall Year in Review: 2013

“Following the trend of the previous two years, 2013 was a quiet year for rockfalls in Yosemite. In all, there were 34 documented rockfalls, which is well below the recent (2006-2012) average of about 55 documented rockfalls per year. The cumulative rockfall volume was about 1500 cubic meters (about 4460 tons), also well below average. Given that 35% of rockfalls occurring since 1857 were associated in some way with precipitation (rain or snowmelt), the fact that 2013 was arguably the driest year on record for California may explain the relatively low level of rockfall activity.

The two most consequential rockfalls in Yosemite in 2013 impacted trails. The first occurred early on the morning of May 11 when a block about 320 cubic meters in volume (about 950 tons) fell from the top of the Panorama Cliff and landed on the John Muir Trail below Clark’s Point. Rock debris covered about 500 meters (1600 feet) of switchbacks, and the trail was closed for several weeks while damaged walls were repaired and the trail cleared.

The second consequential rockfall occurred at about 5 am on the morning of October 5 when a block of about 735 cubic meters (about 2200 tons) fell from Ahwiyah Point north of Half Dome; this was the largest rockfall of 2013. Ahwiyah Point experienced a very large rockfall in 2009 and has had intermittent activity since then. The rockfall on October 5 occurred from the same location as the 2009 event, and also curiously occurred at the same time of day. This early morning timing, combined with the fact that it occurred during the government shutdown, ensured that there were no injuries associated with the rockfall. The Mirror Lake Loop trail, recently reopened after extensive repairs following the 2009 event, experienced some minor damage from boulder impacts. This trail was also closed for several weeks while the source area was monitored and the trail cleared.

Other areas in Yosemite experiencing rockfalls in 2013 include Middle and Higher Cathedral Rocks, the Porcelain Wall west of Half Dome, Glacier Point, Royal Arches, and El Capitan.

It is very likely that there were additional rockfalls in 2013, but these events either were not witnessed or went unreported. If you witness a rockfall of any size, encounter fresh rock debris, or hear cracking or popping sounds emanating from the cliffs, please contact park geologist Greg Stock at 209/379-1420 or by email at greg_stock@nps.gov, or contact Park Dispatch by dialing 911 within the park. Documented rockfalls are added to the park database (http://pubs.usgs.gov/ds/746/), which enables evaluation of rockfall activity to help improve public safety. (G. Stock)”

_______________________________________________________________________

Yosemite Rockfall Year in Review: 2012

“2012 was a relatively quiet year for rockfalls in Yosemite. The most consequential event occurred at about 11:00 pm on January 22 above the Big Oak Flat Road. A boulder some 250 cubic meters in volume (about 745 tons) fell from a cliff above the road, slid down the slope below the cliff, and struck the Big Oak Flat Road, punching a hole in the eastbound lane, tearing out some of the retaining wall, and severely damaging nearly 30 m (100 feet) of roadway. The road was closed for about six weeks for repairs.

Consequential rockfalls also occurred from the Church Bowl area, located between Yosemite Village and the Ahwahnee Hotel. On April 3 and 4, two nighttime rockfalls occurred from the cliff directly above the popular climbing route “Bishop’s Terrace”. The area beneath the climb was devastated by rock debris, with dozens of trees snapped or toppled by the impacts. Small rocks tumbled all the way to the Valley Loop Trail. Climbing routes in this area were temporarily closed until the cliff stabilized.

Other areas in Yosemite experiencing rockfalls in 2012 include Mirror Lake, El Capitan, Ahwiyah Point, Half Dome, Glacier Point, Elephant Rock, Washington Column, and Hetch Hetchy.

In all, there were 43 documented rockfalls in 2012, with an approximate cumulative volume of about 700 cubic meters (about 2,100 tons). Both the number of rockfalls and the cumulative volume for all rockfalls in 2012 are substantially less than that documented in recent years. Although it is not clear exactly why rockfall activity was reduced from previous years, it may relate to the exceptionally dry winter of 2011/2012.

It is very likely that there were additional rockfalls in 2012, but these events either were not witnessed or went unreported. If you witness a rockfall of any size, encounter fresh rock debris, or hear cracking or popping sounds emanating from the cliffs, please contact park geologist Greg Stock at 209/379-1420 or email him at greg_stock@nps.gov , or contact Park Dispatch by dialing 911 within the park. Predicting rockfalls is not yet possible, but understanding the events that do happen is an important step toward this goal. (G. Stock)”

_______________________________________________________________________

Yosemite Rock Fall Year in Review: 2011

“Although not as newsworthy as those of recent years, many significant rock falls occurred in Yosemite in 2011. Probably the most spectacular rock falls originated from the north face of Middle Cathedral rock in July. Three distinct rock falls occurred over a period of several weeks, with a total volume of about 120 cubic meters (about 325 tons). Witnesses in El Capitan Meadow captured impressive photos of the falls and subsequent dust clouds. Fortunately rock debris was contained to the talus slope beneath the cliff and did not affect nearby trails or roads. The Middle Cathedral rock falls occurred during very warm conditions and may have been triggered by thermal stresses. Ongoing monitoring by the National Park Service and U.S. Geological Survey indicates that air temperatures can cause partially-detached rock flakes to deform substantially on both daily and annual timescales.

Another area of notable rock falls in 2011 was Yosemite Falls. On 10 September 2011 a rectangular boulder 2 cubic meters in volume (6 tons) fell from below the upper Yosemite Falls Trail, shattered on a bedrock slab, and fell into the Lower Yosemite Falls amphitheater. Small rock fragments landed in the vicinity of the Lower Yosemite Falls footbridge, but there were no reported injuries. A second and much larger rock fall occurred on 28 October 2011, originating from near the lip of Upper Yosemite Falls. This block, about 20 cubic meters in volume (55 tons), fell from beneath an overhanging roof, skimmed the cliff, and then shattered on impact with the bedrock at the base of the upper falls. Off-trail hikers were present at the base of the falls but avoided injury.

The two most consequential rock falls in 2011 affected park roads. The largest event was not a true rock fall but rather a mass of broken rock and soil that slid onto Foresta Road between Old El Portal and Rancheria during the heavy rain and snow in late March 2011. The volume of this slide was about 1,200 cubic meters (about 3,200 tons). Foresta Road was closed for several weeks as the slide was cleared, and is presently closed again to accommodate engineering of the slope to reduce future slide potential. In the early morning of 7 November 2011, a large boulder (about 18 cubic meters, or 50 tons) and several smaller boulders tumbled from the north wall of the Merced Gorge just east of Arch Rock and embedded themselves in the El Portal Road. Following assessment of the source area, the boulders were removed and the road repaired in time for the morning commute into Yosemite Valley.

Other areas in Yosemite experiencing rock falls in 2011 include Royal Arches, Ahwiyah Point, Half Dome, Glacier Point, the Rockslides, and Hetch Hetchy. In all, there were 53 documented rock falls in 2011, with an approximate cumulative volume of 2,200 cubic meters (6,000 tons). This volume is comparable to the volume that fell in 2010 (2,900 cubic meters) but much smaller than what fell in 2009 (some 50,000 cubic meters); the volume in 2009 was dominated by the large Ahwiyah Point rock fall. Our database of rock falls and other geologic events in Yosemite, begun in 1857, now documents nearly 900 events, making it one of the longest and most detailed landslide databases in the world.

It is very likely that there were additional rock falls in 2011, but these events either were not witnessed or went unreported. If you witness a rockfall of any size, encounter fresh rock debris, or hear cracking or popping sounds emanating from the cliffs, please contact park geologist Greg Stock at (209) 379-1420, or at greg_stock@nps.gov, or contact Park Dispatch by dialing 911 within the park. Predicting rock falls is not yet possible, but understanding the events that do happen is an important step toward this goal. For more information on rock falls and rock fall research in Yosemite, please see the Park’s web page: http://www.nps.gov/yose/naturescience/rockfall.htm. (G. Stick – 1/23)”

_____________________________________________________________

2010 Rock Fall Year in Review

“Although not as newsworthy as those of recent years, many significant rock falls occurred in Yosemite in 2010. The largest occurred on October 11 from the southeast face of El Capitan, midway up the cliff and along the path of Horsetail Falls. This was actually the largest in a series of rock falls from that area over several days. There were no associated injuries despite the fact that these rock falls occurred during the peak of the fall El Capitan climbing season. The cumulative volume of these failures was approximately 1,700 cubic meters (5,000 tons).

Another area of notable rock fall in 2010 was the Rhombus Wall immediately north of the Ahwahnee Hotel. This area was first active in August of 2009, with subsequent failures in September 2009. Quiet for the early part of 2010, the cliff experienced renewed activity beginning in August, with at least five rock falls radiating outward from the initial failure point between August and November 2010. The cumulative rock fall volume over this interval was 187 cubic meters (550 tons). This area of the Rhombus Wall is an impressive example of a progressive failure due to stress redistribution and crack propagation, and presents a unique opportunity to learn more about this complex process.

Ironically, the most serious rock fall of 2010 was also one of the smallest. On October 5, 2010, following several days of intense rain, local children Serra Weber, Carmen Ortiz, and Angel Ortiz were playing on the talus slope near the Church Bowl Picnic Area when a 1.7 cubic meter (5 ton) rock fell from low on the cliff. The rock fell directly onto Serra, pinning her and causing life-threatening injuries. Carmen and Angel ran to the nearby Yosemite Medical Clinic and notified the medical staff, who responded immediately. Serra was flown to a local hospital where she remained for several weeks. Serra recently returned to school in Yosemite Valley, where she, Carmen, and Angel were honored for their bravery during this event.

Other areas in Yosemite experiencing rock falls in 2010 include the Porcelain Wall (on the western shoulder of Half Dome), Glacier Point, Middle Brother, Middle Cathedral, Indian Canyon, and the Merced River Gorge. In all, there were 59 documented rock falls in 2010, with an approximate cumulative volume of 2,900 cubic meters (8,500 tons), more than half of which derives from the El Capitan rock falls. For comparison, the cumulative volume for 2009 was roughly 17 times greater, at about 48,120 cubic meters (142,000 tons); in that year the large volume was dominated by the March 2009 Ahwiyah Point rock fall. Small rock falls are much more likely to occur than large rock falls, but large rock falls represent a far more important source of rock fall debris. The database of rock falls and other geologic events in Yosemite, begun in 1857, now documents over 740 events, making it one of the longest and most detailed landslide databases in the world.

It is very likely that there were additional rockfalls in 2010, but these events either were not witnessed or went unreported. If you witness a rockfall of any size, encounter fresh rock debris, or hear cracking or popping sounds emanating from the cliffs, please contact park geologist Greg Stock at (209) 379-1420, or at greg_stock@nps.gov, or contact Park Dispatch. Predicting rock falls is not yet possible, but understanding the events that do happen is an important step toward this goal. For more information on rock falls and rock fall research in Yosemite, please see the Park’s web page: http://www.nps.gov/yose/naturescience/rockfall.htm (G. Stock – 01/10/11)”

At the above webpage you will find causes of rockfall, what to do in the event of a rockfall, pictures and a map of 154 years of Yosemite valley rock falls (from 1857 to 2009)

_______________________________________________________________

“2009 Rockfall Year in Review:

Several notable rockfalls occurred in Yosemite Valley in 2009.

By far the largest event was the Ahwiyah Point

rockfall on March 28, which originated near the summit of Ahwiyah Point

northeast of Half Dome. This rockfall had an approximate volume of 45,300

cubic meters (about 134,000 tons), making it the largest rockfall in

Yosemite Valley in 22 years (considerably larger than the 1996 Happy Isles

rockfall). The impact of the falling rock on the floor of Tenaya Canyon

destroyed hundreds of trees and generated ground shaking similar to a

magnitude 2.5 earthquake. Rocks continued to fall from this area for many

weeks after the initial failure. The southern portion of the Mirror Lake

loop trail, buried by rock debris, remains closed.

The other area of notable rockfall in 2009 was the Rhombus Wall immediately

north of the Ahwahnee Hotel. On August 26 a series of five rockfalls fell

from midway up the Rhombus Wall, with the largest occurring at

approximately 1:30 pm. Large boulders reached the edge of the talus slope,

and several vehicles in the Ahwahnee parking lot were damaged by smaller

rock fragments. The hotel was evacuated for 48 hours to allow for

geological assessment. Over the next two weeks, loud cracking and popping

sounds were heard emanating from the cliff, suggesting propagation of

cracks within the rockfall source area. This activity culminated in

another rockfall from the source area on September 14, roughly three weeks

after the initial failure. The cumulative volume of the numerous rockfalls

is estimated to be about 1,200 cubic meters, or roughly 3,600 tons.

Twenty-nine parking spaces in the Ahwahnee parking lot were permanently

closed as a result of these rockfalls and the subsequent hazard assessment.

And the park had these notes: “The Ahwahnee, Interim Rockfall Parking Plan

Description: In August 2009, a rock fall occurred on the Rhombus wall high above The Ahwahnee

hotel causing rock debris to scatter on certain portions of the parking lot. In response, the NPS

closed 29 public parking spaces and 12 valet spaces (41 total).”

Here, a photo from the Yosemite Nature Notes 10: Rockfall video (https://home.nps.gov/media/video/view.htm?id=FD5E8943-046C-4A2E-857ADD5C1E8B71AF)

of a man standing on the talus slope below the Rhombus Wall rockfall, with the Ahwahnee Hotel below:

Other areas in Yosemite experiencing rockfalls in 2009 included El Capitan,

Glacier Point, Half Dome, Royal Arches, Cathedral Rocks, and Wapama Falls

at Hetch Hetchy. In all, there were 52 documented rockfalls in 2009, with

an approximate cumulative volume of 48,120 cubic meters (142,000 tons); the

vast majority of this volume was associated with the Ahwiyah Point

rockfalls.

It is very likely that there were additional rockfalls in 2009, but these

events either were not witnessed or went unreported. If you witness a

rockfall of any size, or if you hear cracking or popping sounds emanating

from the cliffs, please contact park geologist Greg Stock at (209)

379-1420, or at greg_stock@nps.gov, or contact Park Dispatch. Predicting

rockfalls is not yet possible, but understanding the events that do happen

is an important step toward this goal. (G Stock 1/25/10)”

_______________________________________________________________________

“Rockfall Year in Review: 2008

Rockfall dramatically influenced human activities in Yosemite Valley in

2008. By far the largest and most consequential rockfalls of 2008 occurred

on October 7 and 8 from above the Ledge Trail near Glacier Point. Repeat

laser mapping revealed the total volume of these rockfalls to be 5738 cubic

meters (17,080 tons). Though not particularly large by Yosemite standards

(for comparison, the July 10, 1996 Happy Isles rockfall was about 5 times

larger, and the March 10, 1987 Middle Brother rockfall was more than 100

times larger), the October 7 and 8 rockfalls were consequential because of

their proximity to Curry Village. Occupied cabins were extensively damaged

by rockfall debris and three minor injuries resulted. A comprehensive

geologic assessment led to the permanent closure of nearly 300 buildings in

the Curry Village area. The other area of notable rockfall in 2008 was El

Capitan, where a ~35 cubic meter (104 ton) rockfall occurred from low on

the southeast face on July 7, and a ~80 cubic meter (238 ton) rockfall

occurred from high on the southwest face on November 4. Other areas

experiencing rockfalls in 2008 included Yosemite Falls, Middle Cathedral,

the Four Mile Trail, Middle Brother, Washington Column, and Basket Dome.

In all, there were 37 documented rockfalls in 2008, with an approximate

cumulative volume of 6385 cubic meters (19,003 tons).

It is very likely that there were additional rockfalls in 2008, but these

events either were not witnessed or went unreported. If you witness a

rockfall of any size, please contact park geologist Greg Stock at (209)

379-1420, or at greg_stock@nps.gov. Predicting rockfalls is not yet

possible, but understanding the events that do happen is an important step

toward this goal. (G. Stock – 1/12/09)”

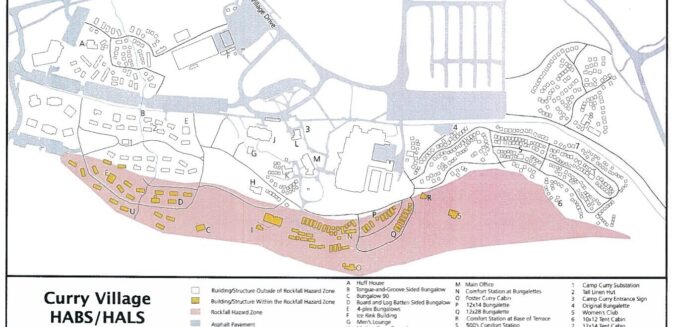

The October 2008 rockfalls above Happy Isles that eventually closed 233 Curry Village (Half Dome Village) cabins, etc. and 43 staff housing units.

Below is a Documentation Map of Curry Village Structures within and outside the Rockfall Hazard Zone (pink area are the structures within the rockfall hazard zone).

see a full sized copy with each building referenced at: Curry Village Rockfall Hazard Zone Structures Project

https://pubs.usgs.gov/sir/2014/5129/

“Here are rockfall safety tips from the Wilderness Safety Action Team.

This text is from the official wording on the rock fall closures posted at trail barricades, but applies to all of us, all the time.

ROCKFALL POTENTIAL IN THE PARK

Rocks and/or ice can fall at any time. While hiking trails, avoid

lingering near talus or steeper slopes, particularly in winter. If you

observe a rockfall in the area, call 911 or 209/379-1992 with information

on the time, location, and duration of the event.

BE RESPONSIBLE—BE SAFE

Rockfalls are a dynamic—and dramatic—natural process. But it is impossible

for the park to monitor for every potential rockfall. In Yosemite, and in

any natural area, it is up to visitors and employees alike to be aware of

their surroundings and enjoy the park safely.

Rockfalls are dangerous and can cause injury or death. Use caution when

entering any area where rockfall activity may occur, such as Valley walls,

climbing areas, or talus slopes.

LEARN MORE

Winter is one of the most active periods for rockfall activity in Yosemite

National Park. As temperatures fall in the evening and warm up during the

day, cracks in the granite can widen, eventually causing rocks to separate

and fall.

To learn more about rockfalls and geology in Yosemite National Park, stop

by any visitor center for an information sheet or visit online at

www.nps.gov/yose. (L.Boyers) ”

From the Daily Report – Yosemite National Park

“Tuesday, March 6, 2012

25th Anniversary of the Middle Brother Rockfall

Saturday, March 10, marks the 25th anniversary of the 1987 Middle Brother rockfall, the largest rockfall in Yosemite’s documented history.

On the afternoon of March 10, 1987, Ranger Jim Tucker received a call from Road Crew Foreman Ralph Parker, who reported that a road crew patching potholes on Northside Drive below the southeast face of Middle Brother had witnessed several small rockfalls and had heard loud cracking noises coming from the cliff face. Upon arrival, Tucker and Ranger Kim Aufhauser witnessed another small rockfall. Tucker, sensing a growing hazard, instructed Parker and his crew to leave the area, and ordered westbound traffic stopped at Camp 4. Ranger Phil Hibbs located Trail Crew Foreman Jim Snyder and the two set up a spotting scope in Leidig Meadow to observe the release point. As the cars piled up behind Camp 4, Tucker received a radio call from Chief Ranger Roger Rudolph, who suggested that Tucker strongly consider reopening Northside Drive. As Tucker and Aufhauser returned to Camp 4 to discuss the situation with Rudolph, they turned back many visitors, including a pair of skeptical hikers who were ordered to leave the area. At they proceeded toward Camp 4, Tucker and Aufhauser heard a tremendous thundering sound.

At 2:47 pm, a huge slab of rock broke loose from the top of Middle Brother. Snyder later described the cliff “unfolding like the stairs of an escalator”. The giant slab disaggregated into a rock avalanche as it hit a prominent ledge and cascaded to the talus slope below. As boulders smashed into the talus slope and sent dust and debris outward, Hibbs yelled, “Run!” Snyder, wanting to run but also wanting to watch the event unfold, tried to do both until he and Hibbs were enveloped in dust and small rock fragments. Stumbling blindly, they made their way to back to Tucker, who was preparing to send out a search party. When the huge dust cloud finally cleared, approximately 180 feet of Northside Drive was covered in rock debris up to 12 feet deep. Several boulders had landed on the far side of the Merced River. There were no injuries, and, aside from a patrol car dented by flyrock, no property damage.

Another large rock fall occurred later that day at 5:10 pm, and smaller rockfalls went on for weeks. The total estimated volume of the rockfalls was 600,000 cubic meters, or 1.4 million tons. Northside Drive was closed for months, and traffic was rerouted to Southside Drive; in anticipation of future rockfalls, reversible detour signs are now posted at key intersections to quickly establish two-way traffic. The 1987 Middle Brother slide provided impetus for Valley Rangers and Search and Rescue to plan and train for large rockfall events, and also initiated a scientific process for documenting and monitoring rockfalls. A triggering mechanism for this rockfall was never identified. (Thanks to former NPS employees Jim Snyder and Jim Tucker for sharing their recollections of this event.) (G. Stock) ”

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

From a National Park Service webpage (the location was not noted):

——————————————————————-

The author of this webpage, (written as a reading assignment for my students), does not give any warranty, expressed or implied, nor assume any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, product, or process included in this website or at websites linked to or from it. Users of information from this website assume all liability arising from such use.