Lodgepole Pines , the most common tree in the rocky mountains, are often the first trees people learn to identify in Grand Teton National Park, because they are almost everywhere in the park (exceptions include high elevations/ alpine and the sagebrush community that makes up most of the valley floor). They can live to be 100-200 years old.

The trees lining the lakeshore of String Lake in the above photo are mostly Lodgepole pines.

cone of a Lodgepole Pine:

The Teton Science School notes that: “Lodgepole pine is indigestible to moose, which is why most of Yellowstone has such a proportionally low moose population – 4 out of every 5 trees over Yellowstone’s 2.2 million acres are lodgepole pine. Look for Yellowstone moose in some of the corners of the park that are richer in firs, willows and aspen. Moose are more abundant in Grand Teton, found in both wetland and mountain habitats.”

Douglas Fir trees are huge when they mature (one measured 400 feet tall and 13’8 in diameter). They can live up to 600 years. At maturity they have thick, corky bark and blunt tipped needles. The NPS notes: “The bark of older trees becomes very thick with reddish-brown, deeply-furrowed ridges. Older trees also loose their lower branches, leaving behind straight trunks. Needles are flat and bristle out around the twigs.”

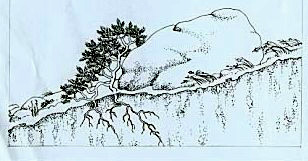

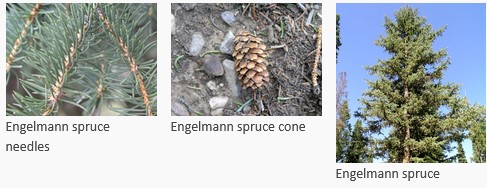

Engelmann Spruce:

can grow as a full sized tree, or, in subalpine / tundra areas, as stunted and dwarfed “krummholz” (crooked wood), as seen in this NPS drawing of a low-lying shrub form of spruce, growing protected from wind by a large rock:

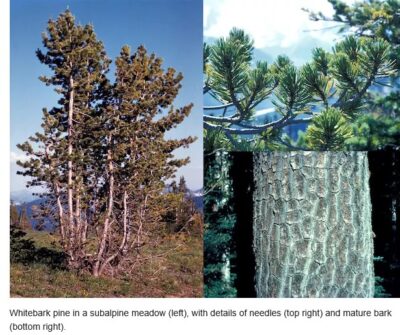

Whitebark Pine

The park service notes: “Whitebark pine is named for the smooth white bark of younger trees and branches. As the tree matures the bark can form brown, scaly plates. It is the only pine in the subalpine zone and can be stunted and shrub-like from exposure to winter winds and heavy snow. Whitebark pine can grow as a single tree, but is often found in clusters of several trunks. It is a five-needle pine, with egg-shaped cones that hang downwards.”

The NPS notes these differences in needles:

“Pine needles are in groups of 2, 3 or 5 and are longer than spruce and fir needles.

Fir needles also have single needles that stick out directly from the branch, feel flat and don’t roll easily in your fingers.

Spruce needles are single needles emanating around the branch and have four sides. Because of the four sided structure they can be easily rolled between your fingers. Normally they feel spikey to the touch.”

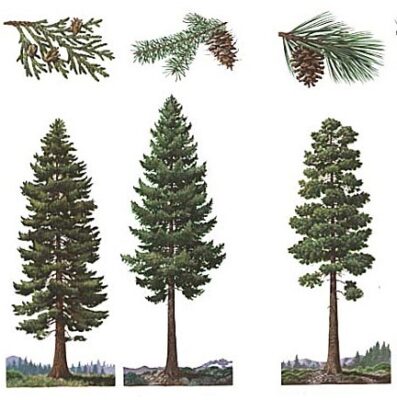

Many people think of trees the shape of the ones shown below as “pine” trees. The NPS has these drawings to show the difference between Western Red Cedar, Douglas Fir, and (growing in Yosemite), Ponderosa Pine:

![]()

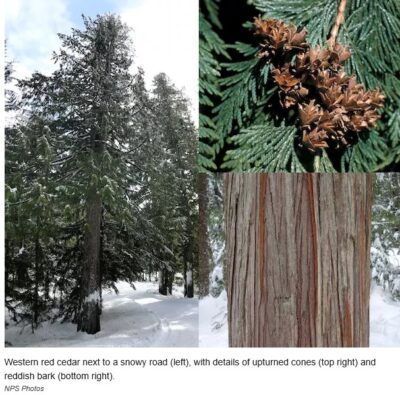

Western Red Cedar

The Park Service notes: “Western red cedar can reach heights of 200 feet (60 m) supported by a thick trunk that can form buttresses at the base. The branches spread widely, drooping before turning upward into “J” shapes. Red cedar has grey to reddish-brown bark that can peel in long strips. Leaves have four rows of scales in a shingle pattern pressed closely to the stem and alternate between pairs of folded and unfolded scales. Cones are green when young, then become brown and turn upwards.” Cones are “egg-shaped with 0.5 in (1.5 cm) scales.”

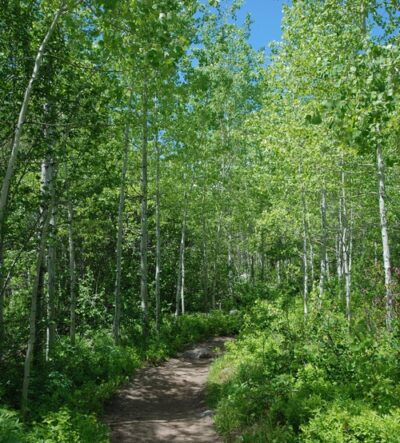

Aspen

The Park service notes: “Aspens (Populus tremuloides) can reach a height between 30 ft. to 65 ft. Bark is smooth with a color of greenish white with black spots and lines. The leaves are small and densely packed on long slender branches…

. . . Quaking aspens provide beautiful scenery and a rich habitat for wildlife. Aspen, the most widely distributed tree in North America, are one of the few deciduous trees hearty enough to survive in a harsh mountain environment. Aspen trees are short-lived, surviving about 120 years. In mountain environments, the brief and dry growing season often prevents aspen seeds from germinating or seedling from surviving. Instead, an aspen’s lateral roots produce vertical shoots, called suckers. Some suckers grow into mature trees, creating a large network of interconnected roots that can produce new trees for over a thousand years. The roots have been shown to exchange resources, such as water and carbohydrates. A patch of genetically identical trees, a “clone”, will sprout new buds and change colors at the same time.”

What you see as a grove of aspen, is actually one tree. One in Utah has 47,000 “stems/sprouts” that cover over 100 acres and weigh about 6600 tons.

below, a trail through green aspen trees in the summer (the leaf buds generally unfold in May):

below, aspen in the fall with Mount Moran in background

fall aspen leaves can be yellow,

or orange

or many shades of bright colors, especially with sunlight flooding through:

Aspens start turning color in September, at first at highest elevations, then lower. Cool weather causes the change. Cool weather without frost is conductive to full development of coloring. Frost can shorten the length of fall coloring season.

You will find aspens many places in the park besides in large groves, such as this one (center of the photo below) outside a Colter Bay cabin:

The NPS notes: “The Aspen’s smooth, white/green bark causes people to mistake this species for Paper Birch. An Aspen’s bark does not flake, turns light green when wet, and tends to take on a thick, dark crust as the tree ages.”

Especially in the winter when leaves aren’t abundant, moose sometimes eat the bark of aspen trees.

On a paddle out to an island on Jackson Lake we found an aspen tree cut down by beavers that you could see the teeth marks in:

The NPS tells us: “The preferred foods of beaver are willow, aspen, and

cottonwood. Where their preferred plants are few or absent, beavers may cut conifer trees and feed on submerged vegetation such as pond lilies.”

Photographer E. J. Peiker has a large panorama photo of the Oxbow with glorious fall leaf color (you can scroll left to right) at

http://www.ejphoto.com/oxbow_bend_pano.htm

__________________________________

Was that a black bear or a grizzly, a coyote or a wolf or a fox we just saw?

Was that a black bear or a grizzly, a coyote or a wolf or a fox we just saw?

Rocky Mountain mammal size comparisons has photos and comparisons of beavers, squirrels, pika, marmot, elk, moose, bison, fox, coyote, wolf, golden-mantled ground squirrel, chipmunk, Red Squirrel (also known as) Chickaree, Unita Ground squirrels, bobcat, lynx, mountain lion (cougar), pine marten, mountain goats, bighorn sheep, pronghorn, grizzly and black bears, tundra swan, trumpeter swan, adult and juvenile Bald Eagles.

Rocky Mountain mammal size comparisons has photos and comparisons of beavers, squirrels, pika, marmot, elk, moose, bison, fox, coyote, wolf, golden-mantled ground squirrel, chipmunk, Red Squirrel (also known as) Chickaree, Unita Ground squirrels, bobcat, lynx, mountain lion (cougar), pine marten, mountain goats, bighorn sheep, pronghorn, grizzly and black bears, tundra swan, trumpeter swan, adult and juvenile Bald Eagles.

___________________________________

Grand Teton National Park birds has photos and details about the most common ones we can hope to see

including Bald Eagle, Red-winged Blackbird, Canada Geese, Clark’s Nutcracker, Golden Eagle, Great Blue Heron.Great Gray Owl, Harlequin duck, Loon, Magpie, Merganser, Northern Flicker (woodpecker), Osprey, Ouzel, Pelican, Peregrine Falcon, Ptarmigan, Raven, Sandhill Cranes, Steller’s Jays, Trumpeter Swan, Western Meadowlark and Western Tanager, with links to calls / songs from most of them to listen to.

and you can Download photos of over a hundred birds of Grand Teton National Park

https://www.audubon.org/climate/national-parks/grand-teton-national-park

___________________________________