Helicopter rescues can be quite difficult or impossible.

Helicopters can’t fly in all kinds of weather, at all altitudes or to all places.

Especially in the mountains, vertical takeoffs and hovering might not be possible where you choose to get hurt.

Rescues endanger rescuers’ lives. Rescues are discretionary; rescuer safety is the first priority.

“You should not expect someone else to bail you out . . . Rescuers often expose themselves to risk in order to save a stricken visitor, but they will not act if it is too dangerous. For example, flight operations in Yosemite after dark are prohibited due to the hazardous terrain.”

is a quote from https://www.nps.gov/yose/blogs/a-winter-trail-run-to-half-dome-nearly-ends-in-disaster.htm

The pilot and flight nurses might have had quite a few rescues in a row to do and not enough sleep just before you get into trouble. They do “fatigue scores every day, where we look at our energy levels. It helps us decide if we’re okay and safe to fly.”

__________________________________

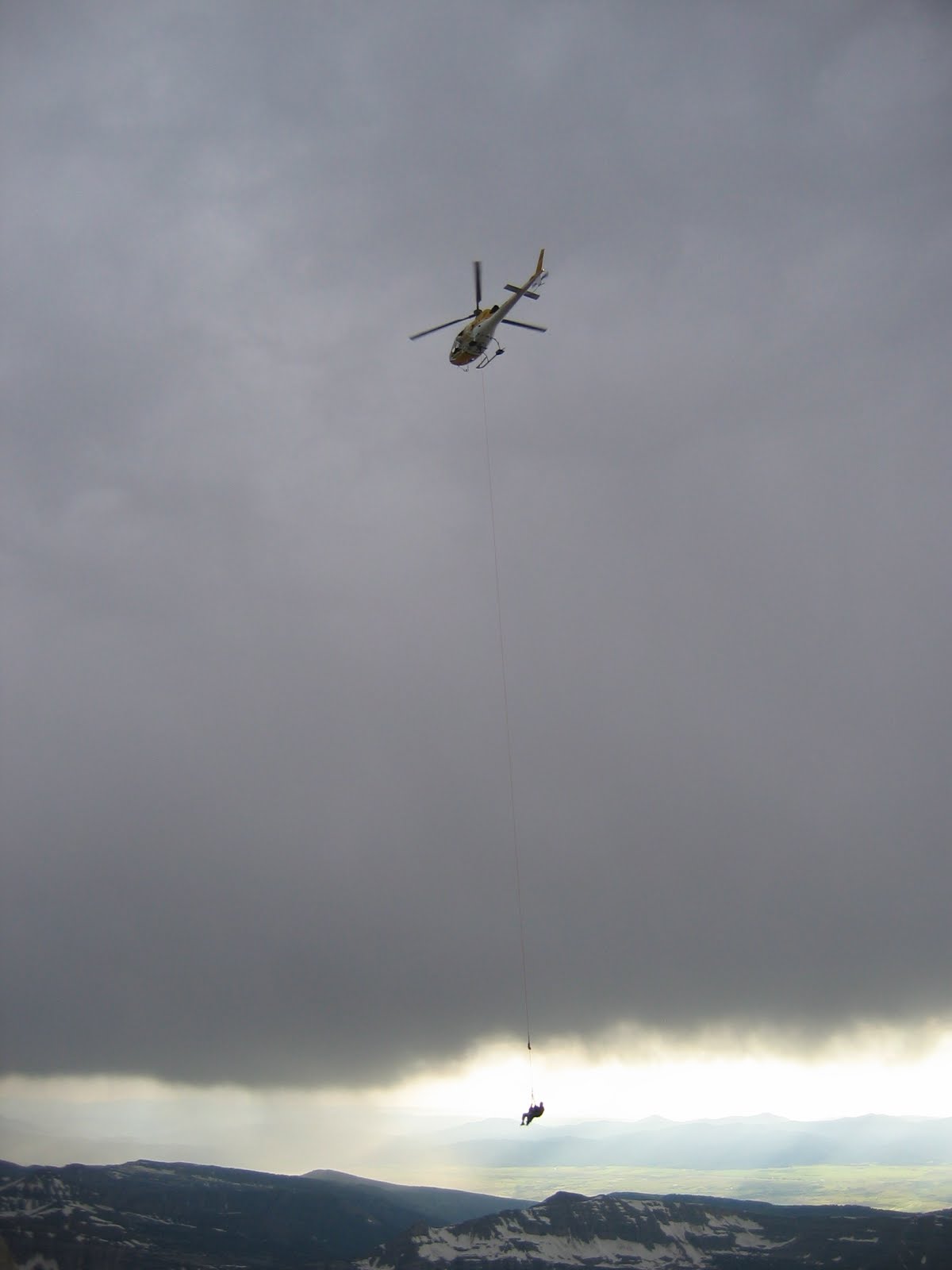

The NPS (National Park Service)explains a short haul:

“When there is no suitable spot to land a helicopter, the shorthaul method is used to place rescue personnel, who are suspended below the helicopter by a double rope system, into a location near the patient; the injured person is then secured into either an evacuation suit or a rescue litter to be airlifted for a short flight to another landing spot where the ship can safely touch down.”

and this other description:

“Short-haul is a rescue technique where an individual or gear is suspended below the helicopter on a 150 to 250 foot rope. This method allows a rescuer more direct access to an injured party, and it is often used in the Teton Range where conditions make it difficult to land a helicopter in the steep and rocky terrain.”

The view down to the victim:

When Teton County Search and rescue was looking for donations for more helicopter training and longer use of a helicopter, they offered these videos:

https://vimeo.com/332297563 “The spotter has to be a short-hauler for a few years prior to becoming a spotter so they have a better understanding of the ship and short-haul operations. Spotters are required to have a better understanding of how the helicopter works as well as the gauges that need to be monitored. Spotters are the eyes for the pilot on the left side of the ship, they monitor the tail rotor clearance, the rotor clearance, torque gauges and pressure gauges and output gauges. They also monitor the short-haulers themselves and the entire scene.”

From an NPS swiftwater rescue manual: “Helo rescue may be appropriate in specific situations, however there needs to be an understanding that this requires sound decision making that matches the capabilities of the involved personnel and aircraft.

Helicopters can access a subject from overhead and potentially avoid hazards that rescuers on the water would be exposed to (e.g., strainers, flood debris, pour-overs, etc.). Extraction of a subject in the swiftwater environment can be efficiently accomplished with a hoist rescue or short-haul technique.

Keep in mind that helicopter rescue accidents do repeatedly occur and they commonly involve poor decision-making.”

There is fascinating reading on how climbers can avoid injuries/stay alive, by Search and Rescue Ranger John Dill,

(including sections on environmental dangers, descents, big wall bivouacs, unplanned bivouacs, loose rock, climbing unroped, leading, falling, learning to lead, the belay chain, helmets, states of mind, rescues, and risks, responsibility and the limits of climbing), at climbing advice.

(Photos on this page courtesy of the National Park Service.)

Grand Teton National Park News Release

Park Rangers Rescue Injured Exum Guide from Symmetry Spire

Grand Teton National Park rangers rescued an injured Exum Mountain guide from Symmetry Spire on Saturday afternoon, August 5. The Exum Mountain Guides office contacted the Jenny Lake ranger station at 2:30 p.m. to notify them that an accident involving their guide, Mark Newcomb, age 39, of Jackson, Wyoming, had just occurred. Newcomb was leading two clients on an ascent of the Direct Jensen Ridge of Symmetry Spire when he took an 80-foot fall at approximately 9,600 feet in elevation.

Newcomb was positioned about 100 feet above his clients, and about 300 feet from the top of the Direct Jensen Ridge on a pitch rated 5.7 on the Yosemite Decimal System. The accident occurred when Newcomb reached for a hand-hold and the block of rock dislodged, causing him to grab a second hold, which also broke off. At the time of the accident, Newcomb was 40 feet above his last point of protection, which held. One of Newcomb’s clients was belaying him, which helped buffer Newcomb’s fall. The clients slowly lowered him 20 feet to the narrow ledge where they were perched.

Park rangers immediately began to coordinate a highly technical rescue response which included extensive air operations, as well as staging rangers in the vicinity of Symmetry Spire for a potential ground response in the event that weather precluded a helicopter evacuation.

Initially the park’s interagency contract helicopter, with three rangers aboard, flew a reconnaissance flight to observe the scene and determine the best approach and technical requirements for the rescue operation. The helicopter then picked up two rangers and inserted them by the short-haul technique onto the vertical rock wall where Newcomb was situated (the short-haul technique is a method by which rangers fly, individually or in pairs, suspended from the helicopter on a double-rope system).

These rangers assessed Newcomb’s condition and provided emergency medical care. Two additional rangers were also inserted via short-haul to assist in the technical operation. While the helicopter hovered above the scene, the two clients were placed into evacuation suits, then attached to the short-haul rope and flown out. After delivering the clients to Lupine Meadows, the helicopter air-lifted a rescue litter to the accident scene and returned to Lupine Meadows to refuel. Meanwhile, rangers placed Newcomb into the rescue litter and prepared him for the short-haul flight. The helicopter returned to the accident scene and hovered while rangers attached the litter to the short-haul line.

Newcomb was flown to Lupine Meadows, arriving at 5:15 p.m. While Newcomb was transported by park ambulance to St. John’s Medical Center in Jackson, the helicopter made two additional trips to Symmetry Spire, flying the rangers out in tandem suspended by the short-haul rope. Newcomb was released from the hospital Saturday evening, after treatment for minor injuries, including lacerations, abrasions and bruises.

Rangers commended pilot, John Bourke, of Heli-Express, for his highly skilled and technical flying. Heli-Express of Atlanta, Georgia has the contract for the park’s interagency helicopter; the ship is an A-Star. This incident required extensive high elevation flying and hovering adjacent to sheer cliff walls with late afternoon winds, an approaching storm, helicopter rotor wash, and people suspended below the ship. There is no margin for error in this type of rescue flying. Bourke made seven round-trip flights to provide reconnaissance, insert rangers, evacuate clients, evacuate the injured climber, and finally retrieve rangers at the completion of the rescue operation.

__________________________________

from the National Park Service morning report of Tuesday, October 24, 2006

Yosemite National Park (CA)Cables Route, Half Dome, Yosemite Valley

– On Sunday, the park received several 911 cell phone transfers regarding a person who’d slipped outside the cables on Half Dome and slid 100 to 150 feet down onto the blank face. He was lying precariously on the face, using only the friction of his body against the rock to stop him from falling more than 800 feet to the ground.

A ranger and a SAR climbing team were immediately dispatched to the incident location. The Yosemite rescue/fire helicopter was unavailable, so a primary rescue team was put on standby to await the arrival of another helicopter to fly them to the shoulder of Half Dome. A helicopter from Sequoia/Kings Canyon responded to the request for mutual aid assistance and was the first available for the mission. Unfortunately, due to the time it took to free up a helicopter, more than two hours passed before technical rescuers were on scene.

SAR technicians then repelled down to the man and rescued him. Although uninjured, he was treated for hypothermia at Yosemite Medical Center and later released.

______________________________

From the National Park Service Daily Report of Thursday, April 10, 2008

Grand Canyon National Park (AZ)

Taser Used On Drunk And Abusive Wrangler

On Thursday, April 3rd, the ranger working at Phantom responded to calls for assistance from the Phantom Ranch staff, who were dealing with a drunken wrangler at the ranch canteen who was being both verbally and physically abusive. The ranger used her taser to subdue the man and take him into custody. Providing her with backup proved a challenge. Phantom is 5,000 feet below the canyon rim and accessible only by foot, mule or helicopter. Since it was almost dark, the park helicopter could not respond. Lack of moonlight also meant that a Department of Public Safety helicopter equipped with night vision goggles was also unable to fly. Two rangers therefore had to hike down the seven-and-a-half-mile long trail to support the ranger during the wrangler’s overnight custody. While waiting the two hours for backup to arrive and still managing the belligerent wrangler, the ranger also had to take care of a 14-year-old girl who had suffered second and third degree burns at the Phantom campground. The burned girl and the wrangler were flown out on the first two park helicopter flights the next morning. [Submitted by John Evans, Park Ranger]

______________________________

Cost of a rescue? Many rescues are simple and fast, such as a child who wanders away from a family campsite. But prolonged recscues are expensive, especially in more rugged and remote parks. Denali in Alaska had three costing $118,000 $127,000, and $132,000. One rescue attempt of two backcountry skiers who died in an avalanche in Grand Teton in 2011 cost $115,000, twice the cost of any previous search and rescue in that park. The helicopter leased for that search cost $33,000. One multi-week search in Yosemite in June 2005 cost $425,000.

Outside magazine has an article on the costs, and legislation in various states charging people for rescues and HIKE SAFE card / Search and Rescue Assistance Card / (Colorado) CORSAR Card:

https://www.outsideonline.com/1986496/search-and-rescue-public-service-not-exactly

The very basics are, if a helicopter comes to rescue you / a member of your group, stay away from where it is landing, any and all debris in the area will be blown around by the rotors. Your eyes and ears (and the victim’s) need protection. Wait for a crew member to come to you OR wait for the pilot to indicate it is safe to approach. Approach and depart in view of the pilot. Do not run. Always approach from downhill in a crouching position. Never go near the helicopter rear tail rotor.

Helicopter safety video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Zzif-RSaQmE

Yosemite Search and Rescue says of the approach of a rescue helicopter: “If ever in trouble, keep waving, even though the aircraft might be flying away from you; you don’t know which way everyone may be looking. Bright colors, reflective objects, and camera flashes are a few excellent tools for being spotted. Additionally, if you DON’T need help, please do not frantically wave at a rescue helicopter.”

see also: Cell phones in the wilderness, which has advice on how/when to use a cell phone to contact 911 in the wilderness and a warning about interference between cell phones, iPods and avalanche beacons.

Grand Teton park spokesperson Jackie Skaggs said because of having an electronic device, “people have an expectation that they can do something stupid and be rescued. Every once in awhile we get a call from someone who has gone to the top of a peak, the weather has turned and they are confused about how to get down and they want someone to personally escort them. The answer is that you are up there for the night.”

People climb over barriers meant to protect them and as a result slide over waterfalls in Yosemite. fatal, near fatal or close call incidents/accidents in camping, backpacking, climbing and mountaineering has press releases about them as well as close encounters with wildlife . . .

See also an index to over a dozen Yosemite National park webpages with park laws, rules, regulations and policies.

Thunderstorm and lightning safety includes a warning about not using your cell phone or IPod during a storm.

Safe distances from wildlife includes reasons to stay away from even friendly seeming animals in parks and charts and photos to better be able to determine and visualize how far away from wildlife you need to stay to be safe (and obey laws that do have penalties).

The use of cell phones for photography (with or without a selfie stick) has made preventable injury or even death by selfie common They were just taking a selfie . . .

AND, even if you can be rescued and taken to a helicopter, the crew might not be able to fly you away quickly, as in this example:

Heat Stroke on a Hot Summer Day

September 08, 2013 from the Yosemite National Park Search and Rescue blog

On Monday afternoon, August 19, 2013, the Yosemite Emergency Communications Center received a 911 call from a hiker on the Upper Yosemite Fall Trail. The caller stated that his brother, a 62 year-old male, had collapsed on the trail below Columbia Rock (approximately one mile from the trailhead). It was a warm, sunny day, with high temperatures predicted at 95°F. The two had been hiking since 6:30am and were returning to the Valley from the top of Yosemite Falls when the subject became dizzy, short of breath, and unable to walk or speak.

Yosemite Search & Rescue (YOSAR) dispatched a hasty team—a paramedic and two other team members—to gain further information and provide medical care. While the hasty team hiked up the trail, the 911-caller reported that his brother’s condition was deteriorating. He had become unconscious, had a rapid pulse, and was no longer sweating. Park rangers quickly organized a carryout team. Once the initial team arrived on scene they found the hiker lying on his back and shaking uncontrollably, with hot, dry skin and a body temperature exceeding 104°F. Rescuers realized he was in critical condition and began cooling him down with IV fluids and cold packs.

He appeared to be suffering from heat stroke.The carryout team carried the hiker down to the trailhead in a wheeled litter and, because of his serious condition, decided to evacuate him to a hospital by a medical helicopter. However, when the helicopter landed in Ahwahnee Meadow, the pilot determined that they could not take off with the additional weight of the patient due to a situation known in aviation as “hot and high.” Hot temperatures combined with high elevation results in air that is less dense: essentially, there are not enough molecules for the helicopter’s rotors to “push” against while lifting from the ground. As a result, an ambulance transported the patient and helicopter crewmembers to a lower-elevation landing zone in El Portal (15 miles away), where the helicopter met them and safely took off with the weight of everyone on board.

The subject was flown to an area hospital, diagnosed with exertional heat stroke, and discharged several days later. He is expected to make a full recovery.

Heat illnesses occur regularly in Yosemite National Park during warm weather, but most cases result in heat exhaustion, which can generally be treated with fluids, salty snacks, and rest in a cooler location. Heat stroke, however, is a less common but life-threatening emergency that requires immediate medical intervention. The two most reliable indicators of the condition are high body temperature (usually over 104°F, though this varies) and altered level of consciousness, but other classic symptoms include nausea, rapid heart rate, hot and red skin, lack of sweat, and seizures. Without treatment, a person suffering from heat stroke will quickly go into shock, suffer multi-organ failure, and die.

Could this emergency have been prevented? The hiker tried to do everything right: he drank water, brought plenty of snacks, wore a hat, and took breaks every 30 minutes in the shade. He started hiking up the trail early in the morning, completing most of the trip before the hottest part of the day. By the time he became ill, he was hiking downhill on a more shaded portion of the trail.

So what went wrong? Rescuers learned that he was taking a medication that made him more prone to heat illness, and that medicine combined with any existing dehydration could have caused his body to drastically overheat. “The first thing that comes to mind,” he said a few weeks later, “is that I probably should have brought more than two liters of water, and should have made myself drink more at times when I wasn’t at all thirsty.”

Many hikers underestimate the amount of water to bring, particularly on hot days or on trails with a lot of sun exposure. On this note, he added, “I also was not aware of the baking effect of the sun as it radiates off the granite, even in early afternoon, turning the trail into a virtual rotisserie at some points.”

If you are going to hike in Yosemite during warm weather, remember to plan ahead. Research your intended route and consider starting early to avoid the afternoon sun. Bring extra water and food, drink water, and plenty of it, before you feel thirsty, wear breathable clothing, and find ways that work for you to mitigate the heat: wearing a hat and/or damp bandana and taking frequent breaks in the shade are good strategies. Remember that simply removing your pack and shoes while resting helps to dissipate body heat. Most important, recognize your limits and turn around before you reach the point that you cannot self-rescue. “I was amazed how quickly it hit,” the hiker who suffered heat stroke said. “One moment feeling wobbly legs and lightheaded, the next in a dream state in a small room that turned out to be the ambulance.”

Here is a NPS video in which Grand Teton National Park rangers discuss their experiences doing short-haul operations.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

The there is no guarantee of rescue webpage

includes accident prevention tips many people who are experienced hikers and backpackers do not know about.

![]()

Half Dome hike advice could also be worth reading.

Helicopters in Search and Rescue:

https://mra.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Helicopters-in-SAR-Rev12Nov21.pdf

——————————————————————-

The author of this webpage, (written as a reading assignment for my students), does not give any warranty, expressed or implied, nor assume any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, product, or process included in this website or at websites linked to or from it. Users of information from this website assume all liability arising from such use.