National parks, (including Yosemite, where this first photo below photo was taken)

have Search and Rescue teams ready at a moment’s notice to help accident victims.

“Yosemite Search and Rescue (YOSAR) can extract an ill or injured party out of the backcountry

on crutches,

by horseback,

or even by helicopter,

but in most cases, YOSAR utilizes a litter carry out team . . . A litter team is comprised of at least six people (ideally more), a metal litter (the basket the subject lies in) and an ATV wheel that attaches to the bottom of the litter. The subject is strapped into the litter, the wheel is screwed onto the bottom of the litter, and then three people hold each side of the litter and guide the wheeled litter along the trail. Additional rescuers can act as a brake for the litter, or the horsepower for the litter, pulling from either end of the litter depending on the slope of the terrain.”

But Search and Rescue can’t always get to victims in a hurry, or even get to them at all.

“Often, rescuers will have to maneuver difficult terrain in precarious areas, navigate in the dark or poor weather conditions, all the while attempting to get the subject to definitive care as quickly as possible. On the other hand, the incident command team is always mindful that in Yosemite it is not uncommon for multiple rescues to take place at the same time, and to adjust accordingly the number of rescuers committed to each rescue.”

At the Grand Teton National Park Backcountry Camping page https://www.nps.gov/grte/planyourvisit/back.htm

There is a Backcountry Travel video

“to help plan your adventure to the high country in Grand Teton National Park.

Learn about safe travel, camping in bear country, clean camping practices and summer weather,”

that says, in part

“. . . you are responsible for your own safety when traveling in the back country.

If someone in your party has an accident or becomes seriously ill, stay calm and assess the situation. Provide first aid and establish a plan.

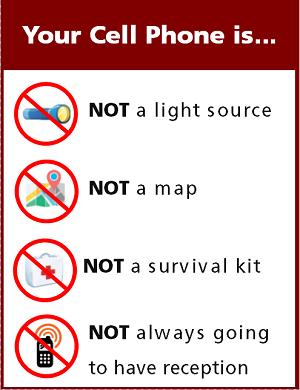

If you need help, rescuers will need to know the nature of the problem, and the patient’s location. Cell phone coverage is not reliable.

You may need to travel some distance to make a call or find assistance and remember,

there is no guarantee of rescue.”

Be clear and detailed when you report to rescuers.

Example of nature of the problem is “the victim is unable to bear weight on a leg/ankle/foot injury”

not just . . . that the victim injured their foot/leg/ankle.

![]()

It can be good to plan in advance for accidents and illnesses. People who travel in the backcountry in minimum groups of four people can have one person stay with the victim, while two others go out together to get help (or find a place where their cell phone does function).

If you have a victim who has an ankle or foot injury, but can walk, you can divide the heavy items or even the entire contents of the daypack or backpack the victim was carrying among the other people in your group.

If they are still having trouble walking,

the walking assist pictured below (also known as the Human Crutch Technique),

can be used, as described in the American Red Cross Lifeguarding Manual

in the section Moving a Victim – non-emergency moves:

“either one or two lifeguards can use this method to move a victim who needs assistance walking.

1/ Stand at one side of the victim, place the victim’s arm across your shoulders and hold it in place with one hand.

2/ Support the victim with your other hand around the victim’s waist.

3/ Walk the victim to safety.”

![]()

(Photo above taken in Grand Teton National park.)

You can have people assisting trade off the jobs of helping the person walk, or carrying heavy gear as you go along.

Do not expect to travel at the same speed as you would have just hiking. People should think safety by taking small steps and by stopping whenever the victim or people assisting want to or need to. If the trail has large steps, it might be best to have two people assisting, one on each side of the victim.

You could plan to stop regularly where there is a stream or lake to take the footwear off the victim’s foot/ankle and soak the injured part in the cold water of the stream / lake, just as you would apply a cold pack during more conventional first aid.

If the victim says that there is too much pain and they can not continue, they should be taken at their word. During an overnight backpack, if you can not get cellphone coverage, you might have to have an additional overnight stop since you will be moving slowly, so you should have always brought some extra food.

And note that you would not use this method to help “anyone you suspect of having a head, neck or spinal injury.”

And don’t aggravate injuries-(don’t move anything you think might be broken).

Prevention: is much better than dealing with injuries.

From National Outdoor Leadership School, (NOLS)

NOLS Common Problems

Majority of all injuries are athletic injuries, such as sprains, strains, etc. to knees, ankles and back from slips and falls around camp or when hiking

Common Causes of Athletic Injury on NOLS courses

Playing games such as hug tag and hacky sack

Tripping while walking in camp

Stepping over logs

Crossing streams, including shallow rock-hops

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

(Are you sure of your balance, especially without hiking staffs?)

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

Putting on a backpack

Lifting a kayak or raft

Falling or misstepping while hiking with a pack (on any terrain)

Falling while skiing with a pack

Shoveling snow

Bending over to pick up firewood

1/3 of reported field incidents = wounds

Blisters are an everyday occurrence = moleskin, second skin, athletic tape

Most common illnesses are preventable gastrointestinal

— Disinfect water, wash your hands, waterless soaps can be useful when water is scarce

“Hypothermia, seizures, heat stroke and pregnancy occurred but with low frequency.”

Conditions most frequently requiring evacuation were: “fractures, dental emergencies, tick fever. athletic emergencies and non-specific body pains.”

At altitude includes this from the Centers for Disease Control:

“Radial Keratotomy

Most people do not have visual problems at high elevations. At very high elevations, however, some people who have had radial keratotomy procedures might develop acute farsightedness and be unable to care for themselves. LASIK and other newer procedures may produce only minor visual disturbances at high elevations.”

“Diabetes Mellitus

Travelers with diabetes can travel safely to high elevations, but they must be accustomed to exercise if participating in strenuous activities at elevation and carefully monitor their blood glucose. Diabetic ketoacidosis can be triggered by altitude illness and can be more difficult to treat in people taking acetazolamide. Not all glucose meters read accurately at high elevations.”

Prevention is the best medicine:

careful gear selection to keep pack weight manageable

fitness, stretching, nutrition

careful walking, helping each other over obstacles

stopping before you are tired

From Mountaineering First Aid (The Mountaineers, Seattle)

contributing causes of accidents

from the American Alpine Club’s Accidents in North American Mountaineering

Bad judgment using equipment:

Climbing unroped

using inadequate equipment: no hard hat, etc.

failure of rappel

placing no or inadequate protection

Performance/judgment error:

exceeding abilities

climbing alone

loss of control on voluntary glissade

party separated, stranded

Environmental conditions:

bad weather

falling rock

darkness

avalanche

Equipment failure:

chock nut/pull out

ascender breakage

The Jenny Lake Climbing Rangers have said:

In the Event of a Life-Threatening Injury

Efforts should be made to obtain assistance as soon as possible. Cell phone notification is by far the most common method of notification. Calling Teton Interagency Dispatch (307-739-3301) directly will avoid potential confusion by eliminating the chance of your emergency call going to another county’s dispatch center. Program this number into your cell phone before your climb. If that number doesn’t work dial 911.

If cell phone service is not available, try sending a text to 911 or a friend or family member and have them call for help. Text messages require less signal strength and often transmit when cell phone calls cannot connect. Download the new BackcountrySOS App! https://www.backcountrysos.com/ BackcountrySOS is a simple-to-use smartphone app that allows you to quickly get your status and location information to emergency personnel.

If possible, send an extra member of your party or try to notify an adjacent party on the mountain, who can get to an area with cell phone reception or hike out to get word to the Jenny Lake Ranger Station (or any Visitor Center). Do not leave the injured climber alone unless absolutely necessary.

Information needed by the rescue team includes:

1) the exact location of the injured party

2) the time of the accident

3) the nature and extent of injuries & medical care being provided

4) equipment at the scene (ropes, hardware, first-aid kit, etc.)

5) the number of people with the injured party

6) the plan of action (if any).

read the entire current page of advice at: https://tetonclimbingaccidents.blogspot.com/

A retired mountaineering ranger in Denali (Alaska) National Park offers this at https://www.nps.gov/dena/planyourvisit/survival.htm

“Everyone has a personal responsibility to maintain self-sufficiency in the wilderness and should always base decisions on getting back on their own.

Your best resource is the ability to think in a controlled manner when a life-threatening crisis is happening.

Prevention, not treatment, is what ultimately will save your life in the wilderness. There is a notable difference between a gamble and a calculated risk. A calculated risk considers all the odds, justifies the risk, and then makes an intelligent decision based on conservative judgment. A gamble is something over which you have no control and the outcome is just a roll of the dice.

You cannot make intelligent decisions in the wilderness if you do not understand the risks.

Never give up; the will to live is a valuable asset. Sometimes people perish simply because they fall short on perseverance.

As a rule, if you die in the wilderness you made a mistake;careless judgment has a sharp learning curve.

Wilderness rescues in Alaska are often dangerous to the rescuers and always weather-contingent.

People do not realize the devastating impact that their accidents have on friends and loved ones.

The prerequisite to misadventure is the belief that you are invincible or that the wilderness cares about you.”

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

If someone gets hit by lightning, or even nearly hit, they may be thrown a distance, so if they need ventilations (also known as rescue breathing and/or artificial respiration) you’ll need to treat them as a spinal injury and use a modified jaw thrust rather than head-tilt chin-lift. If you are out in the wilderness, away from quick EMS help, you might need to give ventilations for a whole hour or even longer. Don’t give up if they still have a pulse. NO, you won’t get electrocuted by touching someone who was hit by lightning.

see also Thunderstorm and lightning safety which includes the answer to the question:

Why can’t you swim during a lightning storm? A strike on a lake doesn’t kill all the fish in the lake.

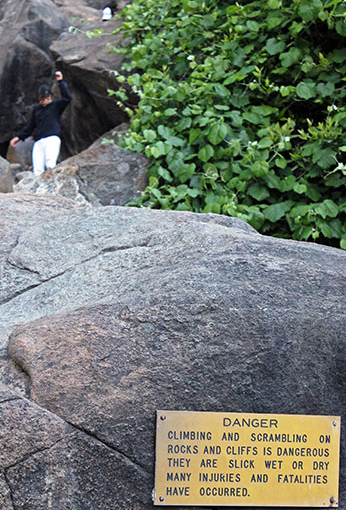

This warning sign below, often ignored, is at the viewing platform at the end of a short trail to Bridalveil Fall in Yosemite National Park. (The picture below is from: A Common Yosemite Search and Rescue where it says: “Danger signs are not there to ruin our fun. They are often posted in places with a large accumulation of past accidents.”)

It can take quite awhile for a rescue team to get to you. https://www.nps.gov/yose/blogs/open-ankle-fracture-at-bridalveil-fall.htm

“Open Ankle Fracture at Bridalveil Fall .. .The subject, a 48 year-old male, along with his nine-year-old son, had hiked to the viewing platform below Bridalveil Fall. The pair then left the established trail to scramble up the boulder field toward the base of the waterfall (left), bypassing signs that advise against leaving the trail. Although the boulders were dry, they were still extremely slick; over the years, the boulders have been polished smooth by water from Bridalveil Fall (even rescuers that day, wearing approach shoes with sticky rubber soles, had trouble with their footing).. .”

and see:

Depending on a GPS unit to intentionally be separated from your hiking partners can lead to confusion or even disaster. Be certain that the people you are with are happy with this prospect. GPS is not infallible

HIKING SECRETS and etiquette on the Hiking Advice webpage include hiking in the heat, preventing and/or dealing with blisters, logistics of hiking, a day hike gear list, Half Dome hiking advice, winter hiking and the answer to the question: When is the best time of day to cross a mountain stream?

Crossing streams safely includes advice from Mount Rainier National Park, Yellowstone National Park, Great Smoky Mountains, and Yosemite National Park.

When you camp at 7,000 or 8,000,or 9,000 plus feet elevation, you will probably feel out of breath at first and may even get a headache and lose appetite. You can get more sunburned. Read At altitude for advice. It includes why your tent mate might seem to stop breathing.

backpacking advice has these sections:

Must bring for each large group (or perhaps for each couple or person),

Must bring backpacking for each person,

Some (crazy?) people think these are optional for backpacking,

Backpacking luxuries(?),

Do not bring these backpacking,

To keep down on weight backpacking,

Don’t rush out and buy,

BACKBACKING FOOD, Low-cook backpacking foods,

Yosemite National Park WILDERNESS PERMITS,

Leave no trace camping has these basic principles:

Plan Ahead and Prepare

Travel and Camp on Durable Surfaces

Dispose of Waste Properly

Minimize Campfire Impacts

Respect Wildlife

Be Considerate of Other Visitors

examples and details of how easy this can be are at: Leave no trace

Even though you might not be able to use your cell phone to place a call in many areas of national parks, each person in each hiking group should carry one on each hike.If you each take a photo of all the hikers in your group on your cell phone just before you start a hike, this can be used to document what each person was wearing, maybe quite helpful if someone gets lost.

see also: Cell phones in the wilderness which has advice on how/when to use a cell phone to contact 911 in the wilderness and a warning about interference between cell phones, iPods and avalanche beacons.

You can’t always expect a helicopter rescue

You can’t always expect a helicopter rescue

The use of cell phones for photography (with or without a selfie stick) has made preventable injury or even death by selfie common

They were just taking a selfie . . .

“If you are close enough to take a selfie with an animal, you are too close. ”

Wilderness first aid outline includes initial snakebite care, tick removal

and the note “Most of your victims in the wilderness may be dehydrated. Anyone tired and cranky, headachey is probably also dehydrated and may be starting to suffer from heat exhaustion.)

Heat illnesses (heat exhaustion and heat stroke, dehydration)

Can a person who is prescribed an epi-pen risk going into the wilderness? and some sting prevention notes are at: Anaphylaxis quick facts

From a Teton County Search & Rescue report

Tired Hikers in Alaska Basin

DATE 7/5/22

TIME 6:11 p.m.

DURATION 10 hours, 11 minutes

ATTENDEES 5 team members

BOARD CALL ONLY

WHAT HAPPENED? Two 20-year-old companions called dispatch from Sunrise Lake in Alaska Basin to request support. The female and male reported being too exhausted to continue their hike back to the trailhead. The BOA recommended they set up camp and rest for the night and continue in the morning. On the next day, they called dispatch again to say they were sore and couldn’t carry their packs and wanted someone to come in and carry their gear out for them.

The BOA decided to monitor the pair’s progress, and eventually, the hikers made it out of the backcountry on their own.

From a Teton County Search & Rescue report

Injured Hiker in Alaska Basin

DATE 7/14/2020

TIME 8:47 a.m.

DURATION 13 minutes

ATTENDEES 3 team members

PERSON HOURS 0.7

WHAT HAPPENED? A hiker in Alaska Basin called to say that

his friend had a cut on his lower leg. They controlled the

bleeding and had exited Teton Canyon, but didn’t have a car

there. Because the hikers were at a trailhead and not in the

backcountry, TCSAR advised the hikers to call a cab or find a

ride some other way.

From a Teton County Search & Rescue report

Stranded Campers on Static Peak

DATE 9/7/2020

TIME 11:23 p.m.

DURATION 20 hours, 25 minutes

ATTENDEES 8 team members

PERSON HOURS 163.3

WHAT HAPPENED? The Board of Advisors was alerted to a group of seven backpackers who’d been pinned down in the Static Peak area by the season’s first winter storm. The group was huddled in one tent, with the caller saying they wouldn’t be able to survive the night. The board discussed the situation with GTNP, which was already busy coordinating other rescues in the park. With the call originating from outside the park, it would be a TCSAR matter. Given the late hour, severe weather

and distance from the trailhead, the BOA told the caller that resources would not be sent and that they’d have to make it through the night on their own. At 6 a.m., the BOA reconvened and determined that the backpackers would be hiking out via GTNP and that no rescue was necessary. One TCSAR team member stayed in contact with the party as they hiked out to monitor their progress.

(Note to on-line users not in my classes: this is a study sheet. It is not complete instruction in the topic named in the webpage title.)

The author of this webpage, (written as a homework reading assignment for my students), does not give any warranty, expressed or implied, nor assume any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, product, or process included in this website or at websites linked to or from it. Users of information from this website assume all liability arising from such use.