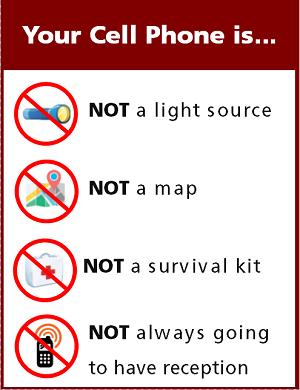

Some people like the safety of a cell phone, others think it wrecks the ‘wilderness experience’.

Turn off cell phones unless you must use them,

if you do use a cell phone, use it out of sight and sound of other people.

The biggest problem is people who bring a cell phone

instead of the essential gear/knowledge/and good judgement and expect to be bailed out,

or who take risks they wouldn’t without the backup of a phone.

Cell phone coverage in the wilderness is at best variable and intermittent. Satellite phones do have better coverage, but even they are not 100% reliable as they can occasionally drop signals or otherwise malfunction.

![]()

Denali National park warns:

“A note on technology in remote environments: Technology has a tendency to fail us just when we need it most. This trend is even more common in cold, wet, harsh environments which can wreak havoc on fragile equipment. Batteries die, the cold kills circuit boards, plastic housings break, etc. Your best contingency plan will always be self-sufficiency. Even when communication devices do work, rescue help cannot always reach you in a timely manner.” https://www.nps.gov/dena/planyourvisit/mountaingear.htm

From Risk Management for Outdoor Leaders, by the National Outdoor Leadership School:

“Never forget that a peril of portable phones is a loss of self-reliance. With the spread of cell towers and satellites, our society now has unrealistic expectations for rescues in the wilderness. Search and rescue personnel tell tales of adventurers who expect quick responses in the middle of nowhere while they sit passively and do little to help themselves.”

Before you place the call be sure of how desperate your situation is and be certain you can’t handle it yourselves. Stop and think rather than allowing your emotions to take control. Perform a complete, careful assessment following all the steps in that first aid class you took. Listen for the whistle your supposedly lost friend would be blowing (you all carry one, don’t you?)

“Cell phones can be helpful, but they are not 100% reliable. Dead zones exist even in Yosemite Valley, and phones are worthless without a charge. While it’s important not to rely on cell phones, they can nevertheless be lifesavers, so consider one for each person in case members of the party become separated” is a quote from

https://www.nps.gov/yose/blogs/a-winter-trail-run-to-half-dome-nearly-ends-in-disaster.htm

![]()

The National Association for Search and Rescue had this advice:

“Be SMART about using a Personal Locator Beacon (PLB) or other Satellite Emergency

Notification Device (SEND, e.g. Spot) or cell phone during backcountry or wilderness travel.

1. If you answer ‘No!’ to ‘Would I go there without my PLB, SEND or cell phone?’ then don’t go there with it!

2. Would you normally do something that might fracture your pelvis, freeze your hands or feet, kill you by heat stroke, suffocate you under snow, drown you or get you lost for days? If you answer ‘NO’ – then don’t do it relying on a signaling device!

3. Don’t think “It won’t happen to me – that happens to someone else.” Backcountry and wilderness travelers must know how to:

- Prepare for,

Recognize and

Prevent an emergency

4. Always use these devices for the unforeseen – not as a last resort tool to handle what should be foreseen. It is dangerous and irresponsible to think they “allow” going somewhere or doing something you are not prepared or experienced to do.

5. Carrying an electronic signaling device does not make you safe. No distress beacon or cell phone offers warmth, shelter or first aid. They only make it easier to summon emergency help – after you are injured, lost – or worse. And once rescuers have been notified, weather and terrain conditions may prevent or delay them from reaching or even finding you.

6. When you activate any emergency signaling device, a full-scale emergency response will begin using local, state and / or national emergency agencies. It is only appropriate when a true emergency exists.

7. PLBs and SENDs are useful devices that save lives. You should think ahead about when to use one responsibly.

(‘SEND’ – A distress signal transmitter that uses satellites for communication, other than a PLB (Personal Locator Beacon, for individuals), ELT (Emergency Locator Transmitter, for aircraft) or EPIRB (Emergency Position Indicating Radio Beacon, for boats.)”

Consider how much effort will be put into a rescue, here quotes from various National Park Service reports:

“The rescue team consisted of 16 park employees.”

“The litter team ran two miles, fully loaded with gear, in order to expedite a wheeled litter carryout to a waiting ambulance.”

“More than 30 NPS employees and a contract helicopter were utilized to search the major drainages and canyons within the highest probability search area.”

“A full-scale search involving three helicopters, dog teams, hikers, horses, and swift-water trained personnel is ongoing.”

“After Teton Interagency Dispatch Center received notice of the accident, two rangers immediately began hiking and running to the location. They covered approximately four miles with an elevation gain of 2,700 feet in 90 degree heat, reaching Bell in less than two hours.”

“Joining the search were the park’s aircraft, Metro PD SAR teams, a Metro PD helicopter, and an interagency fire crew and helicopter.”

Grand Teton park spokesperson Jackie Skaggs said because of having an electronic device,

“people have an expectation that they can do something stupid and be rescued.

Every once in awhile we get a call from someone who has gone to the top of a peak, the weather has turned and they are confused about how to get down and they want someone to personally escort them. The answer is that you are up there for the night.”

If you call, be ready to give specific details of the problem and your plans and alternate plans. Realize that you need to be concise in the first sentence you speak over a cell phone of your problem, location and needs, as the cell phone could stop working before you can finish what you need to say.

From Yosemite SAR: “Keep in mind that cell phones that work fine at home, may not work in the park. If yours works and you need emergency help, it is imperative that you call 911 instead of texting” (a relative/friend to get help) because text messages can be lined up in a queue and sent out belatedly.

Until they get a better system in place, when you call 911 from a cell phone you will get dispatch for the Highway Patrol in a far-off city instead of the park rangers or forest service where you are traveling. The Highway Patrol dispatch may have no idea how to quickly contact the people you need. If you intend to use that cell phone, find out what the eight digit direct dial phone number is for the help you could need. It can often be found in the National park newspaper you get when you enter the park (or the newspaper online).

See advice from North Cascades National Park about making the call.

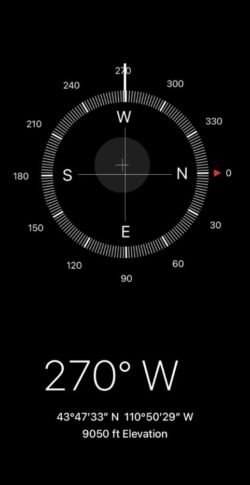

Find a compass, altitude, latitude and longitude on your cell phone here.

Knowing the elevation you attained on a hike and or climb can be fun for the been-there-and-done-that part of your adventure. Below, a photo taken of the compass app on a cell phone at Lake Solitude, Grand Teton National Park:

The 270 degrees W (west) shows the direction the cell phone was pointing, useful for orienting to a typographical map.

__________________________________

This next article was quoted in its entirety in the Yosemite National Park Daily Report –

Tuesday, April 13, 2004

Cell phone use in parks pitting safety vs. vistas

By Becky Bohrer

UNION-TRIBUNE ASSOCIATED PRESS

April 12, 2004

It was a sunny spring day in Yellowstone National Park, and tourist Judy Brendalen paused for a midday snack at a roadside picnic table. Close at hand in her purse was her cell phone just in case. “I think for emergency purposes, you need it,” Brendalen, of Clearbrook, Minn., said as she relaxed, not even noticing a cell phone antenna tower on a nearby Wyoming ridge.

Cell phones have long been virtually unavoidable on city streets and in shopping malls. But they are now showing up in some of the very places people go to escape such things: national parks. For park managers, this is a challenge. Officials say they want to ensure public safety and meet the needs of visitors. But they also must protect park resources and the visitor experience. There is no set policy on how to strike this balance, on what role cell phones and the antenna towers they require should play in their parks.

Some conservationists worry that parks run the risk of becoming too civilized, even scarred by development.

“You have to keep in mind what the purpose of a park is,” said Laura Loomis, government affairs director with the National Parks Conservation Association. “There’s visitor enjoyment, but it shouldn’t be at the sacrifice of the resource. And the resource includes the landscape.”

At least 15 national parks have one or more cell towers within their boundaries, according to regional park service offices, though they acknowledged the number may be incomplete. Also, many parks may receive cell coverage in some areas from towers outside their boundaries. Park service officials say that, on a national level, they do not track the number of cell phone towers in the parks. The permit process for telecommunications sites is done at the local park level, where officials are supposed to study the potential effects a proposal may have on such things as the environment and view and to provide an opportunity for public comment, said Lee Dickinson, special park uses program manager with the National Park Service. “It’s important to keep the evaluation on the park level because they understand the park resource,” she said.

Some groups have questioned the process through which such sites are approved and say they would like to see more open discussion. One Yellowstone tower, near Old Faithful, has been criticized as an eyesore by groups such as the Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility. Among the concerns raised by PEER about such development is the potential it sees for the “death of solitude in national parks.” “It’s possible you could come to a trail in Yellowstone and see someone yakking on the phone to their stockbroker,” said Dennis McKinney, development director at PEER. For Michael Scott, that kind of scene detracts from every else’s enjoyment of the park experience. “Providing for the safety and enjoyment of national parks is necessary to address,” said Scott, executive director of the Greater Yellowstone Coalition. “But the concern on the other side of that is, if you take your family to Old Faithful to enjoy it . . . is it appropriate to have people talking on their cell phone?”

Lane Baker, Yellowstone’s deputy chief ranger, said many people expect to be able to use cell phones and that officials can’t dictate how tourists use them. “We can’t control what people do on their cell phones,” she said. “You can’t control what they do at Old Faithful like you can’t control what they do in downtown New York.”

Baker also said cell phones in the park have a definite positive side, making a difference in the way officials can receive and respond to calls. “As an emergency responder, I wouldn’t want to do my job without one,” she said.

Yellowstone is developing an “antenna management plan” that would look at such things as the park’s needs and help with long-term planning, spokeswoman Cheryl Matthews said. The park has five cell towers, including two that were built on existing equipment, and all are in developed areas within the park, she said. “We felt, with the requests we were getting, that it was appropriate to move forward with this,” she said. Matthews said she couldn’t estimate how much of the park receives cell coverage, but noted that only about 2 percent of Yellowstone is developed.

The issue isn’t just at Yellowstone. At Grand Teton National Park, also in Wyoming, there are cell towers within and just outside the boundaries. Some backcountry areas have cell coverage, and that may create a false sense of security for tourists, said Joan Anzelmo, a park spokeswoman. “With that access, people think, ‘With my cell phone, I can be rescued.’ That’s not a good attitude to have,” she said. “When you head out to the backcountry, you need to be knowledgeable and prepared” to deal with hazards without help.

But cell phones have saved lives. Last July, a desperate cell phone call from 13,000 feet on the Grand Teton alerted rescuers that lightning had struck a party of 13 climbers near the summit. Rangers flew to the mountain by helicopter and were able to pluck the most badly injured from the mountain before nightfall. One climber was killed by the lightning strike, but the others survived.

But on the other side of the equation, Yosemite spokesman Deb Schweizer said the park in California also has gotten calls from hikers who are simply pooped and want a lift out. They get a polite refusal. “Just because you’re tired doesn’t mean we’re going to send someone out,” she said.

Roxanne Dey, a spokeswoman at Lake Mead National Recreation Area in Arizona and Nevada, said she wasn’t even aware of the location of towers in that unit until they were pointed out to her recently. She said about 10 percent of the park has coverage with the three towers within its borders and that she feels safer, particularly when she is with her children, having her cell phone along. “I wouldn’t want a cell tower next to the Washington Monument or in the most popular hiking area at Lake Mead,” she said. “But I think you can strike a balance.” (InsideNPS – 4/13/04)

![]()

advice from North Cascades National Park

In a discussion of 1998 search and rescue incidents, Rangers at North Cascades National Park warned that cell phone calls for help “influence search and rescue for better and or worse”…

Carrying A Cell Phone?

Packing a telephone with the climbing gear is a fairly recent development, but now, not uncommon. Climbers carrying cell phones are finding that in many (mostly high elevation) areas of the North Cascades, reception can be quite good. However, others attempting to use a cell phone as an emergency communication tool have found reception to be fickle, at times with unexpected consequences.

Cell phone use also remains controversial amongst wilderness purists. While agencies generally have not taken a position, from a practical standpoint, rangers have observed that the technology is definitely influencing the search and rescue business for better or worse.

In several incidents, phones have successfully alerted rescuers to mountain accidents in North Cascades National Park, allowing rescue to begin hours before it would have without phone notification. But with equal frequency, the use of a phone in an initial distress call has resulted in what is referred to as a “bastard search” — a response by rescuers for a situation in which their assistance is unnecessary.

For those climbers packing a phone to potentially use in the event of an accident, the following information could prove useful:

If you are in North Cascades National Park the best number to call is Park Dispatch at (360) 873-4500, ext. 37. Dialing 911 or the appropriate County Sheriff’s office will work, but will take longer, as they then call the North Cascades dispatch when it is clear the caller’s location lies within the Park.

Always state your location and cell phone number early in the call in case connections fail and a callback is necessary.

Be aware that if you get through once, it does not mean a connection can be made a second time, even from the very same location. Consequently, it is important to communicate clearly the purpose of your call in your first connection, and if you are requesting assistance.

Depending on circumstances, a plan to ‘call back’ later without a clear first call might very well give you a rescue response you didn’t intend to initiate. Agencies with emergency response duties are required to investigate and resolve all reported incidents.

As phone technology advances, the unsuredness of dependable connections in remote areas may be eliminated. But for now, climbers are cautioned to not substitute the phone for preparedness. And if putting one to use in summoning help, be aware that a well-planned call can make a lot of difference.

Advice for climbers from Grand Teton National Park: (please note that you should confirm the phone number below when you arrive in the park and go to a Ranger Station to talk about your climbing plans.) http://tetonclimbingaccidents.blogspot.com/

In the Event of a Life-Threatening Injury

Efforts should be made to obtain assistance as soon as possible. Cell phone notification is by far the most common method of notification. Calling Teton Interagency Dispatch (307-739-3301) directly will avoid potential confusion by eliminating the chance of your emergency call going to another county’s dispatch center. Program this number into your cell phone before your climb. If that number doesn’t work dial 911.

If cell phone service is not available, try sending a text to Teton Interagency Dispatch (307-690-3301). If that doesn’t work try a friend or family member and have them call for help. Text messages require less signal strength and often transmit when cell phone calls cannot connect.

Download the new BackcountrySOS App! BackcountrySOS is a simple-to-use smartphone app that allows you to quickly get your status and location information to emergency personnel.

If possible, send an extra member of your party or try to notify an adjacent party on the mountain, who can get to an area with cell phone reception or hike out to get word to the Jenny Lake Ranger Station (or any Visitor Center). Do not leave the injured climber alone unless absolutely necessary.

Information needed by the rescue team includes:

1) the exact location of the injured climber

2) the time of the accident

3) the nature and extent of injuries & medical care being provided

4) equipment at the scene (ropes, hardware, first-aid kit, etc.)

5) the number of people with the injured party

6) the plan of action (if any).

From the National Park Service Morning Report,

Thursday, February 23, 2006

“Grand Teton National Park (WY)

Skier Rescued Near Taggart Lake

Rangers rescued an injured backcountry skier near the west shore of Taggart Lake on Saturday evening, February 18th. A 42-year-old woman from Jackson, Wyoming, fell and seriously injured her right leg while skiing in Avalanche Canyon and was unable to ski out to the Taggart Lake trailhead on the Teton Park Road. The woman’s companion employed a cell phone to make a 911 call. While rangers on snowmobiles headed toward her location, the woman and her companion fashioned a makeshift splint to stabilize her leg. They met up with three other skiers who were in the vicinity, and they helped her in her efforts to ski further. The group worked their way down Avalanche Canyon for about two miles before a change in terrain made it difficult for the woman to continue. Rangers reached her at 7:20 p.m. and placed her in a rescue sled towed behind a snowmobile. After they transported her to the trailhead, she was driven by private vehicle to St. John’s Medical Center in Jackson for treatment of her injuries. Rangers credited the woman, her companion, and the other backcountry skiers for their emergency self-rescue work. [Submitted by Jackie Skaggs, Public Affairs Specialist]”

Jeff and Kathy, the 08-09 + Tuolumne winter rangers, recommended http://www.esavalanche.org (and click on advisory) for people considering the multi day ski trek to the Tuolumne Meadows ski hut. There they had a note about interference between cell phones, iPods and avalanche beacons:

“Another issue is radio frequency interference (“RFI”). With so many different electronic devices carried by backcountry recreationalists these days, complete testing of every possible device is infeasible so I’ll cover this briefly here. I have found that a *transmitting* cell phone (CDMA band) or FRS/GMRS radio can cause interference to varying degrees in some (but not all) beacons. But no beacons suffer RFI from an on-yet-not-transmitting phone or two-way radio. Far more importantly, playing an iPod will cause RFI to vary degrees in *all* avalanche beacons at close range. My general conclusions with RFI are: Be very careful if deciding to call for help while simultaneously searching with an avalanche beacon; and if you are touring with any brand of avalanche beacon, never listen to an iPod. (I am very serious about this: the potential for an iPod to be inadvertently left on and then cause interference in a beacon search is dangerous.)”

see also: GPS is not infallible

You can’t always expect a helicopter rescue

You can’t always expect a helicopter rescue

Thunderstorm and lightning safety includes a warning about not using your cell phone or IPod during a storm.

The use of cell phones for photography (with or without a selfie stick) has made preventable injury or even death by selfie common They were just taking a selfie . . .

Safe distances from wildlife includes reasons to stay away from even friendly seeming animals in parks and charts and photos to better be able to determine and visualize how far away from wildlife you need to stay to be safe (and obey laws that do have penalties).