This webpage details the major points of the material in the wilderness first aid curriculum at De Anza College.

It is meant to be used with a full Red Cross First Aid text and class lecture / videos and is not complete instruction in first aid.

The curriculum is in dark blue. Headings with no text accompanying them are covered fully in the Red Cross text or in class lecture. Headings with text accompanying them may only include part of what is covered in class. There are many links to optional reading.

Sierra Club wilderness first aid

“rule of fours”

you can live 4 minutes without oxygen,

4 hours without shelter,

4 days without water,

4 weeks without food

(but that may be the limit of any reasonable expectation of survival).

Describe how to respond to and provide care for a person who is suddenly ill in a wilderness environment

Yosemite Search and Rescue recommends: “Recreating with medical conditions: Medical conditions should not prevent recreationists from enjoying Yosemite’s vast wilderness; however, proper management of medical conditions is essential for a successful wilderness experience. Whether hiking in a party of two or ten, it is important for fellow hiking companions to be aware of medical conditions in the group and proper treatment and management of medical conditions. Recreationists who are prescribed medication should carry the medication (plus a few extra doses) in a personal pack so that they don’t miss a dose if an outdoor outing goes awry or longer than anticipated.”

1.Tell how to prevent poisoning emergencies, remove an embedded tick, and treat a snake bite – with knowledge of the wrong ways typically used.

Tips to prevent poisoning emergencies, from NOLS Wilderness first aid and other sources

read labels for information on toxic substances

if you cut down on weight by packing various over-the-counter medicines in small containers, copy and pack the use instructions with them

cook outside or in well-ventilated tents or snow shelter (But remember that if you cook in a tent you risk food odor contamination and future visits by animals.)

check a sweet drink container for possible insects before you drink from it

NOLS says to identify plants before you eat them (but you have a huge risk it you eat mushrooms and even many leafy greens or seemingly tasty berries)

be aware of foot placement

look before you reach under logs, overhangs or onto ledges

collect firewood before dark

shake out clothing, footwear and sleeping bags

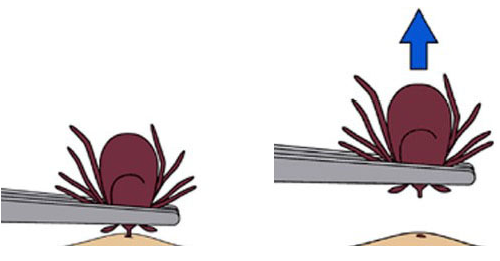

TICKS- don’t try to apply fingernail polish, alcohol, a hot match, a lit cigarette, petroleum jelly, lotions or other potions,

they do not work and they increase the risk that the tick will salivate or regurgitate into you and increase infection

Guidelines for removing a tick (from the Centers for Disease Control)

If you find a tick attached to your skin, simply remove the tick as soon as possible. There are several tick removal devices on the market, but a plain set of fine-tipped tweezers works very well.

How to remove a tick

1. Use clean, fine-tipped tweezers to grasp the tick as close to the skin’s surface as possible.

2. Pull upward with steady, even pressure. Don’t twist or jerk the tick; this can cause the mouth-parts to break off and remain in the skin. If this happens, remove the mouth-parts with tweezers. If you cannot remove the mouth easily with tweezers, leave it alone and let the skin heal.

3. After removing the tick, thoroughly clean the bite area and your hands with rubbing alcohol or soap and water.

4. Never crush a tick with your fingers. Dispose of a live tick by

o Putting it in alcohol,

o Placing it in a sealed bag/container,

o Wrapping it tightly in tape, or

o Flushing it down the toilet.

Follow-up

If you develop a rash or fever within several weeks of removing a tick, see your doctor:

• Tell the doctor about your recent tick bite,

• When the bite occurred, and

• Where you most likely acquired the tick.

The National Park Service says:

To dispose of a live tick, submerse it in alcohol, place it in a sealed bag or container, or wrap it tightly in tape. Consider placing the tick in the freezer inside a sealed plastic bag and label it with the date, time, and location where you likely picked up the tick, in case you wish to send it off for lab testing at a later date. Never crush a tick with your fingers!

Guidelines for Initial Snakebite Care

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said:

“What TO DO if You or Someone Else is Bitten by a Snake

Try to see and remember the color and shape of the snake, which can help with treatment of the snake bite.

Keep the bitten person still and calm. This can slow down the spread of venom if the snake is venomous.

Seek medical attention as soon as possible.

Dial 911 or call local Emergency Medical Services (EMS).

Contact your local Poison Control Center at 1-800-222-1222.”

-Note that poison control in Canada is 1-844-764-7669

(1-844-POISON-X);

“Apply first aid if you cannot get the person to the hospital right away.

Lay or sit the person down with the bite below the level of the heart.

Tell them to stay calm and still.

Wash the wound with warm soapy water immediately.

Cover the bite with a clean, dry dressing.

What NOT TO DO if You or Someone Else is Bitten by a Snake

Do not pick up the snake or try to trap it, capture it or kill it (this may put you or someone else at risk for a bite).

Do not apply a tourniquet.

Do not slash the wound with a knife.

Do not suck out the venom.

Do not drink alcohol as a pain killer.

Do not drink caffeinated beverages.

Do not apply ice or immerse the wound in water.” (There will be swelling, but if you put ice on a rattlesnake bite you make it worse.)

and you might want to:

Remove any jewelry that might constrict swelling

Mark the initial swelling with a pen and the time

Do not touch a dead venomous snake (even decapitated) since the jaws can have a reflex hours later and still bite

(and the bite can contain a large amount of venom).

• Do NOT disregard the bites of small or juvenile venomous snakes. They are born equipped with venom that is just as potent as adult venomous snakes.

(Of the average 7,000 people bitten by snakes in the US every year, less than 5% die.

25 – 30% of adult rattlesnakes bites have no venom injected.)

In a Los Angeles Times article we read:

“Between 7,000 and 8,000 people per year are bitten by venomous snakes in the United States, but only five of them die each year, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In 10% to 20% of rattlesnake bites, the creatures do not release venom, probably because they don’t see the human as prey, said Dr. Cyrus Rangan, assistant director with the California Poison Control System.

In venomous bites, a victim’s chance of surviving can drop if they have an allergic reaction to the venom, or if a fang reaches directly into a vein or artery, sending the poison flowing throughout their body, he said.

Most commonly, snake bite victims are men between 18 and 25 years old who are intoxicated and “doing something very stupid,” like trying to pick up the snake, Rangan said.

Todd said the snakes usually aren’t to blame: “Apparently the real issue is testosterone poisoning or alcohol use, not the snakes themselves.”

See also: http://www.nps.gov/yose/naturescience/rattlesnake.htm

If you decide to hike off-trail, please be prepared that you can step between rocks and unknowingly step near a rattlesnake, or “crevices can hide scorpions, spiders, and yellow jacket nests”. https://www.nps.gov/yose/blogs/Nevada-Fall-Rattlesnake-Bite.htm

the above advice is from: hiking advice

The CDC (Centers for Disease Control) says:

One of the ways to prevent snakebites is “avoid putting hands or feet into places that cannot be visually inspected”.

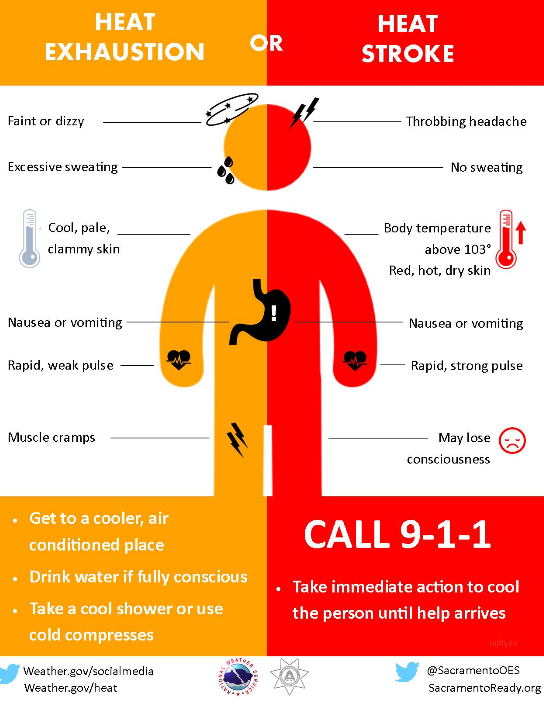

2.List risk factors and care for exertional heat stroke

Sunstroke and sun poisoning are not the correct words / terms / phrases

for professional rescuers such as lifeguards, EMTs, nurses, and other emergency room personnel,

or even just people who do first aid,

to use for heat stroke, heat exhaustion or even sunburn.

Those at Greatest Risk for Heat-related Illness

Young children and the elderly

Those involved in strenuous activity in a hot environment

Those with preexisting health problems

Those using alcohol, illicit drugs or medications like antihistamines

Those who have had a heat-related illness in the past

Unaccustomed to the heat

Those who are dehydrated

Signs and Symptoms of Heat-related Illness

Headache

Cool, moist, pale, or ashen skin (earlier stages)

Dry, red, hot skin (later stages)

Nausea

Exhaustion

Progressive loss of consciousness

Rapid, weak pulse (later stages)

Rapid, shallow breathing (later stages)

High body temperature (later stages)

Care for Heat Exposure

Remove victim from hot environment

Give small amounts of cool water to conscious victim

Have victim lie down in a cool or shady area and elevate legs if possible

Loosen or remove clothing

Apply cool, wet towels or cold packs to wrists, armpits, groin, and legs

Fan victim

Yosemite Search and Rescue Ranger John Dill wrote:

“No Yosemite climber has died from heat, but a half-dozen parties have come close. Too exhausted to move, they survived only because death by drying-up is a relatively slow process, allowing rescuers time to get there.

Temperatures on the sunny walls often exceed 100° Fahrenheit, but even in cool weather, climbing all day requires lots of water.

The generally accepted minimum, two quarts per person per day, is just that – a minimum. It may not replace what you use, so don’t let the desire for a light haul bag be your overriding concern, and take extra for unanticipated delays. Do not put all your water in a single container, and watch out for leaks.

If you find yourself rationing water, remember that dehydration will seriously sap your strength, slowing you even further. It’s not uncommon to go from mere thirst to a complete standstill in a single day. Continuing up might be the right choice but several climbers have said, “I should have gone down while I could.”

purifying drinking water while hiking, camping and backpacking

Heat Stroke on a Hot Summer Day

September 08, 2013 from the Yosemite National Park Search and Rescue blog

On Monday afternoon, August 19, 2013, the Yosemite Emergency Communications Center received a 911 call from a hiker on the Upper Yosemite Fall Trail. The caller stated that his brother, a 62 year-old male, had collapsed on the trail below Columbia Rock (approximately one mile from the trailhead). It was a warm, sunny day, with high temperatures predicted at 95°F. The two had been hiking since 6:30am and were returning to the Valley from the top of Yosemite Falls when the subject became dizzy, short of breath, and unable to walk or speak.

Yosemite Search & Rescue (YOSAR) dispatched a hasty team — a paramedic and two other team members — to gain further information and provide medical care. While the hasty team hiked up the trail, the 911-caller reported that his brother’s condition was deteriorating. He had become unconscious, had a rapid pulse, and was no longer sweating. Park rangers quickly organized a carryout team. Once the initial team arrived on scene they found the hiker lying on his back and shaking uncontrollably, with hot, dry skin and a body temperature exceeding 104°F. Rescuers realized he was in critical condition and began cooling him down with IV fluids and cold packs.

He appeared to be suffering from heat stroke. The carryout team carried the hiker down to the trailhead in a wheeled litter and, because of his serious condition, decided to evacuate him to a hospital by a medical helicopter. However, when the helicopter landed in Ahwahnee Meadow, the pilot determined that they could not take off with the additional weight of the patient due to a situation known in aviation as “hot and high.” Hot temperatures combined with high elevation results in air that is less dense: essentially, there are not enough molecules for the helicopter’s rotors to “push” against while lifting from the ground. As a result, an ambulance transported the patient and helicopter crew members to a lower-elevation landing zone in El Portal (15 miles away), where the helicopter met them and safely took off with the weight of everyone on board.

The subject was flown to an area hospital, diagnosed with exertional heat stroke, and discharged several days later. He is expected to make a full recovery.

Heat illnesses occur regularly in Yosemite National Park during warm weather, but most cases result in heat exhaustion, which can generally be treated with fluids, salty snacks, and rest in a cooler location. Heat stroke, however, is a less common but life-threatening emergency that requires immediate medical intervention. The two most reliable indicators of the condition are high body temperature (usually over 104°F, though this varies) and altered level of consciousness, but other classic symptoms include nausea, rapid heart rate, hot and red skin, lack of sweat, and seizures. Without treatment, a person suffering from heat stroke will quickly go into shock, suffer multi-organ failure, and die.

Could this emergency have been prevented? The hiker tried to do everything right: he drank water, brought plenty of snacks, wore a hat, and took breaks every 30 minutes in the shade. He started hiking up the trail early in the morning, completing most of the trip before the hottest part of the day. By the time he became ill, he was hiking downhill on a more shaded portion of the trail.

So what went wrong? Rescuers learned that he was taking a medication that made him more prone to heat illness, and that medicine combined with any existing dehydration could have caused his body to drastically overheat. “The first thing that comes to mind,” he said a few weeks later, “is that I probably should have brought more than two liters of water, and should have made myself drink more at times when I wasn’t at all thirsty.”

Many hikers underestimate the amount of water to bring, particularly on hot days or on trails with a lot of sun exposure. On this note, he added, “I also was not aware of the baking effect of the sun as it radiates off the granite, even in early afternoon, turning the trail into a virtual rotisserie at some points.”

If you are going to hike in Yosemite during warm weather, remember to plan ahead. Research your intended route and consider starting early to avoid the afternoon sun. Bring extra water and food, drink water, and plenty of it, before you feel thirsty, wear breathable clothing, and find ways that work for you to mitigate the heat: wearing a hat and/or damp bandana and taking frequent breaks in the shade are good strategies. Remember that simply removing your pack and shoes while resting helps to dissipate body heat. Most important, recognize your limits and turn around before you reach the point that you cannot self-rescue. “I was amazed how quickly it hit,” the hiker who suffered heat stroke said. “One moment feeling wobbly legs and lightheaded, the next in a dream state in a small room that turned out to be the ambulance.”

3.Describe assessment, prevention and treatment of mild to severe hypothermia

Hypothermia is when your entire body cools, “a decrease in the core temperature of the body that impairs intellectual, muscular and cardiac function” (Medicine for Mountaineering).

It is the number one cause of death in the wilderness and it is almost always preventable.

Factors Affecting Normal Body Temperature

Air temperature: cold, but does not have to be near or below freezing

Air temperature hot, especially with humidity

Wind, especially if victim is wet/sweaty

Clothing – inadequate (see a description of good stuff at Snow or rain camp must-haves)

Do not go to sleep with cold, wet feet.

Intensity of activity – fatigue

Body’s ability to adapt (physical fitness level)

alcohol – causes skin blood vessels to vasodilate, more warm blood supply moves to outer skin layer – hypothermic person gets colder as a result

not eating enough – not enough fluids causing dehydration

(most of your victims in the wilderness may be dehydrated.)

ignoring any of the above, which can start a precipitous fall into hypothermia or heat stroke

Those at Greatest Risk for Cold Exposure

Young children and elderly

Those without adequate equipment, clothing, or training for cold environment

Those with health problems

Those using illicit drugs, medications, or alcohol

People who don’t realize they can get hypothermia

Signs and Symptoms of Hypothermia

Various sources have different definitions of what constitutes mild, moderate or severe hypothermia.

Cool skin

It starts with feeling cold. Your body tries to correct this by making you shiver. It can progress quite quickly from this stage if not corrected.

Shivering, that progresses to shivering you can’t stop voluntarily and then to waves of violent shivering

Poor coordination (sometimes uncoordination can precede shivering) (a good skier who becomes clumsy, someone who can’t zip up their jacket, hiker who stumbles on loose rock and falls behind the group, someone who can’t pass a heel-to-toe walk) A staggering gait can be an early sign even though body temperature is still normal because cold directly affects nerves to legs

Glassy stare, Difficulty speaking, (the brain can be one of the first things to go because it is most sensitive to cold)

Indifference, apathy, personality changes, especially irritability

Decreasing level of consciousness

Rigid posture, curls into fetal position

Care for Hypothermia

Initially, exercise can warm people up the fastest, such as hiking briskly to nearby shelter.

Remove victim from cold, wet, windy environment, protect from any further heat loss.

Remove wet clothing and put on dry clothing. Put on more layers of clothing, wind protection.

Summon more advanced medical personnel

Reassure victim

Handle victim gently

Place victim in dry blankets or clothing and wrap in plastic if available. Ensolite pad under the victim, space blanket around them. Put person in a sleeping bag with a warm person. Hot water bottle, drinking water bottle full of warm water, warm rocks placed against side of chest, neck and abdomen (but the victim might not notice if these are too warm so test them yourself).

More calories if they can eat. Warm food is good but not necessary. Avoid alcohol, caffeine, nicotine.

For our level of training and due to space limitations, treatment of severe hypothermia will not be covered here. Prevent it.

Hypothermia symptoms: The Umbles: grumbles, mumbles, fumbles, stumbles, tumbles.

Hypothermia causes loss of fine motor skills, so we fumble, stumble and tumble.

Our brains can have ill effects from the cold fairly quickly and we mumble and grumble.

Grand Teton National Park says this in a Backcountry Camping brochure:

“Hypothermia (lowering of body temperature) is a serious condition that may lead quickly to death. Hypothermia is often due to exposure from a storm or a swamped boat. Watch for signs of hypothermia: uncontrollable shivering, incoherent speech and exhaustion. Seek shelter, replace wet clothing and provide warm, nonalcoholic liquids. In serious cases, place the undressed victim in a sleeping bag with another undressed person. Always carry rain gear and extra clothing. Dress in layers and avoid wearing cotton. ”

4.List the causes of, prevention of, how to limit damage from and treatment of frostbite

frostbite causes (from NOLS Wilderness first Aid and other sources)

preoccupation with having fun and you don’t notice painfully cold toes transitioning to toes with no feeling that won’t wiggle

cold, especially with wind chill

moisture (replace wet clothing or cover and insulate wet clothing)

wrong clothes (many survival books will tell you: Cotton Kills! / no percentage of cotton in your socks or long underwear; see a description of good clothes at Snow or rain camp must-haves)

lack of insulating clothes, lack of good raingear

contact with supercooled metal or fuel

any interference with blood circulation, such as a cramped position, tight clothing ( even wristwatches), local pressure (tightly laced boots)

dehydration (10% dehydration causes 30-40% decrease in thermal control)

Prevention: (see above) and make everyone in your group stop occasionally and wiggle their fingers and toes, flex their facial muscles. Watch each other for gray or distinctly white skin. Change into dry, non-cotton socks regularly as needed.

(From a NOLS (National Outdoor Leadership School) Wilderness case study:

“cold, damp socks is not a sign of toughness, rather, it’s a bad habit.”

Cold injuries to toes/feet can surprise “people who thought their feet were just a bit cold.”)

Frostbite

Superficial frostbite (frost nip is reversible – put your fingers in your armpits or on partner’s stomach)

Most common form of frostbite

Skin is frozen, underlying tissues are not

Involves loss of feeling and sensation

Person feels tingling sensation when rewarmed

Deep frostbite is totally preventable if you are careful

Skin is white and waxy

Skin is firm when palpated

Swelling and blisters may be present

When rewarmed, skin appears red with areas of purple and blue

5.Describe signs, symptoms, principal reasons for and treatment of dehydration

A Grand Teton National Park wilderness brochure says:

“Stay hydrated! High elevation and low humidity will drain your body of fluids.

Drink water before you start your hike, carry plenty of water with you

and drink fluids after your hike. . . .

Untreated water may contain Giardia, Campylobacter or other harmful organisms that cause intestinal disorders with severe diarrhea.

Treat ALL backcountry water by boiling, with chemical methods or a portable water filter. ”

Signs and symptoms of dehydration (from NOLS Wilderness First Aid and other sources)

”

Early Signs

Fatigue

Heat oppression

Thirst

Irritability

Dizziness

Dark, concentrated urine

Headache

Loss of group cooperation

Later signs

Rapid pulse, pale sweaty skin

Weakness and nausea

Loss of balance

Changes in mental awareness

Skin tenting

Serious signs

Inability to swallow, swollen tongue

Sunken eyes

Loss of consciousness

Delirium

Treatment for Dehydration

DRINK, DRINK, DRINK”

(Red Cross first aid station protocols: rehydrate as rapidly as tolerated, but at least 16-32 ounces of water an hour). Don’t try to force liquids down the throat of someone who can’t hold the water bottle/mug to their own mouth and swallow.

(NOLS) In severe cases, evacuation may be necessary

Dehydration at Altitude (from Medicine for Mountaineering)

main cause is the need for rapid and deeper breathing

also decreased fluid consumption caused by need to purify water or melt snow, and the dulling of the sensation of thirst that accompanies the loss of appetite at altitude

solution: force yourselves to drink large amounts of water. Thirst alone is often not a reliable indicator. Needs can be greater than four liters per day.

(Most of your victims in the wilderness may be dehydrated. Anyone tired and cranky, headachey is probably also dehydrated and may be starting to suffer from heat exhaustion.)

And the NPS gives this warning about lack of salt in your diet

“HYPONATREMIA (water intoxication) – An illness that mimics the early symptoms of heat exhaustion. It is the result of low sodium in the blood caused by drinking too much water and losing too much salt through sweating.

Symptoms: nausea, vomiting, altered mental states, confusion, frequent urination. The victim may appear intoxicated. In extreme cases seizures may occur.

Treatment: have the victim eat salty foods, slowly drink sports drinks with electrolytes, and rest in the shade. If mental alertness decreases, seek immediate help!”

The New York Times reported: “Aggressive messaging is part of the strategy to prevent heat-related illness.” in Grand Canyon National park. ” On one trail, a sign with a character referred to as “Victor Vomit” warned against day hiking to the river and back.”

“They thought they’d be fine — they’ll be exhausted, maybe they’ll have muscle cramps, they’ll have to drag themselves out. But they’re really not picturing hours of uncontrollable vomiting, or renal” (kidney) “failure.” The range of possibilities extends to permanent disability and death. “Those are the things that we’re worried about when we’re talking to people down there.”

Sitting on a cooler in the shade during a break, the trainer and emergency medical services coordinator, James Thompson, explained the evolution of the park’s approach since the advent of P-SAR in the late 1990s, when the core message to hot weather visitors was “Drink, drink, drink.”

“That pushed people into becoming hyponatremic, where they lose a bunch of salt but they can’t regain it,” Mr. Thompson said, a situation that can lead to dangerous brain swelling and seizures. If hikers readily absorbed the message that they needed to hydrate at all costs, they often forgot the corollary: sweating through the dry heat robs your body not just of fluids, but of the sodium that’s essential to muscle and nerve function. The park has since altered its public messaging and deployed blood testing machines called I-STATs, usually reserved for use in hospitals, in the backcountry. The machines allow rangers to diagnose hyponatremia on the spot and administer IVs with a highly concentrated saline solution.

“It’s not a slam dunk, but it can save patients a lot of money and a lot of risk,” Mr. Thompson said.

The salty snacks offered by rangers are part of an approach known as P-SAR, or “preventive search and rescue,” pioneered here after an extreme heat wave in 1996 led to hundreds of cases of heat exhaustion and five fatalities.

6.List risk factors for altitude sickness. List signs, symptoms and treatment of acute mountain sickness, high altitude pulmonary edema, and high altitude cerebral edema

“”symptoms of dehydration and malnutrition can mimic symptoms of Acute Mountain Sickness” https://www.nps.gov/dena/planyourvisit/part2medicalissues.htm

At altitude has info about sunburn, hiking, diet at higher altitudes. It includes material from the class on why your tent mate might seem to stop breathing and links to High Altitude Cerebral Edema and High Altitude Pulmonary Edema tutorials.

Do not use a Gamow bag (portable hyperbaric device) as a substitute for descending.

7.List and explain the reasons behind the symptoms of shock

Signs and Symptoms of Shock

Restlessness/irritability

Drowsiness/loss of consciousness

Rapid pulse, breathing

Pale, ashen, or bluish/cool/moist skin

Excessive thirst

Nausea and vomiting

Body Compensates for Blood Loss

The heart beats faster

Breathing rate increases

body moves blood / fluid from areas where it is less needed (stops making saliva, less blood to skin — superficial blood vessels contract; less blood to digestive system) to where it is needed (brain)

8.Demonstrate first aid for an insect sting and know ways to avoid insect stings

Brightly colored clothing, flowery prints and black attract insects more than white, green, tan or khaki without prints/patterns. Choose light colors rather than dark, Nature.com reported that “the US military changed its dress shirts from dark blue to light blue in part to mitigate mosquito biting.” Wear shoes and keep arms and legs covered if possible. Long-sleeved shirts and pants work to some degree 24 hours a day, but we counted fifty mosquitos in my husband’s back during a lunch stop up on a Mount Rainier trail.

In brush, put your socks up over pant legs.

Perfumes in shampoo, lotion, suntan lotion, deodorant and other cosmetics attract.

Don’t bring clothes camping that have been rinsed or dried with mosquito-attracting scented softeners (plus, dryer sheets can make a greasy stain on clothes if they get stuck to them, and the softeners can decrease the lofting and wicking of garments).

My allergist told me to take vitamin B1 for a month before camping trips, BUT a brochure on West Nile virus from the Santa Clara County (California) Vector Control District said “Vitamin B1 and ultrasonic devices are not effective in preventing mosquito bites.”

Along with adults wearing long sleeved clothing and using an effective repellent, it recommends “place mosquito netting over infant carriers when you are outdoors with babies.”

Food attracts, store it in closed containers; avoid open garbage receptacles. We’ve had some success when we grill a salmon by leaving the head a bit of a ways aside awhile before we start cooking to attract any yellowjackets to it instead of our meal. (Of course we don’t set it where it will simply attract insects to other campers and of course we pick up the head after the meal and we wouldn’t do this where or when there was any chance of an animal finding the head.)

A fact sheet on the subject of yellow jackets from the Santa Clara Valley Urban Runoff Pollution Prevention Program said, in part:

“Outdoors do not drink soft drinks or other sugary drinks from open containers. Use cups with lids and straws, and look before you sip. Do not carry snacks containing meat or sugar in open containers.

Avoid going barefoot, especially in vegetation.

Do not squash a yellowjacket. When crushed, many yellowjacket species emit a chemical that can cause other nearby yellowjackets to attack.

Always examine wet towels or wet clothing before you pick them up outdoors.”

insect repellant has answers to questions about the percentage of DEET needed in an effective insect repellant, toxicity allergies, and more.

Can a person who is prescribed an epi-pen risk going into the wilderness? Anaphylaxis quick facts

G. Describe how to respond to and provide care for a person who is injured in a wilderness environment

A Western Journal of Medicine article on injuries in the wilderness in California said:

“Contrary to popular belief and media attention . . . most wilderness injuries in California are not due to exotic causes, (wild animal attacks, rock climbing, hang gliding and so on). Rather they are due to common activities, such as hiking, walking, skiing and driving. Fighting and substance abuse, for example, account for more than three times as many injuries as rock climbing. . .

The “most common cause of mortality is heart disease.”

From National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine “Diarrhea is the most common illness limiting long-distance hikers. Hikers should purify water routinely, avoiding using untreated surface water. The risk of gastrointestinal illness can also be reduced by maintaining personal hygiene practices and cleaning cookware.” Preferably use a water purifying pump, but bring chemical means should the pump die. Be sure the chemical method you choose will work against cryptosporidium and giardia and note how long (four hours??) the water must be treated for the treatment to be effective. Note also that iodine tablets are not effective against cryptosporidium / giardia and some people are allergic to iodine.

Wash your paws!

Burns:

From Practice Guidelines for Wilderness Emergency Care by the Wilderness Medical Society

BURNS

Prevent burns, including being extra careful when boiling water.

Ibuprofen is the best over- the-counter pain management for burns. If small enough, cover with Spenco second skin.

Do not pack burns in ice which are over 20% of body surface

Do not leave wet coverings on burns for more than two hours to reduce the risk of hypothermia

Elevate burned extremities to reduce swelling

Have victim gently and regularly move burned areas as much as possible

from From Medicine for Mountaineering

Fluid loss (from damaged capillaries allowing blood serum to pour into the burned tissues), occurs with all burns, both partial and full thickness, but in previously healthy young adults does not achieve life-threatening proportions if the burns cover less than ten to fifteen percent of the body surface.

A person with a major burn usually dies within 12 to 19 hours unless appropriate fluid therapy is instituted.

Burn shock causes a burn victim to vomit anything taken by mouth. If they are not vomiting, the fluids often remain in the stomach and are not absorbed. Because appropriate fluids (IVs) are rarely available in wilderness situations, a major burn in a remote area usually requires immediate evacuation by the fastest means possible.

All full thickness burns larger than one inch diameter eventually require surgical therapy- debridement and skin grafting.

Mild = blistering partial thickness burns of less than 15% of the body surface, with less than two percent full-thickness burns.

Moderate and major = requires hospitalization = worse than mild, including significant burns of the face, eyes ears, feet or genitals and buttocks.

If any question about the severity of the burn exists… evacuate. Persons with major burns are often deceptively alert for several hours until fluid losses become severe.

– – – –

Do not drain intact burn blisters.

– – – – –

https://home.nps.gov/yose/blogs/partial-thickness-leg-burns-in-little-yosemite-valley.htm

July 21, 2012 Posted by: Yosemite Search and Rescue

At about 8:45 a.m. on Friday, July 6, a 52 year-old female backpacker staying in the Little Yosemite Valley backpacker’s campground suffered partial thickness burns (2nd degree burns) to both her legs. After eating breakfast, the subject and her fellow backpackers prepared to wash their dishes by bringing a pot of water to boil. The group was using a single-burner backpacking stove, placed on top of a low stump. The pot of boiling water was accidentally spilled on the subject’s legs, causing partial thickness burns to the subject’s entire right knee and an estimated two-thirds of the circumference of the subject’s left calf. Unfortunately, this incident was not a singular event this summer; multiple cases of burns occurring in park campgrounds have been treated at the Yosemite Medical Clinic.

Placing a camp stove on a secure and unmovable surface and being careful when moving hot items to and from the stove are two tips to keep in mind to avoid accidents. Additionally, heightened vigilance when children are near camp stoves and campfire rings is critical-in the morning, children will often approach a campfire ring that appears innocuous, only to plunge their hands in the ashes and be burned by hot embers from the previous night’s fire.

The subject suffering burns at Little Yosemite Valley waded waist-deep in the Merced River, where she stood in the water for approximately 20 minutes to stop the burning. When NPS rescuers arrived on scene, the subject’s body temperature had dropped to 95.4°F and the skin associated with the burns had sloughed off. Using the rule of palms, rescuers estimated that 8% of the subject’s body had been burned. The subject’s wounds were irrigated and wrapped in dry gauze, and the subject was flown by helicopter out of the backcountry to the NPS helibase at Crane Flat, where she was transferred to an ambulance and transported to Sonora Regional Medical Center.”

Consider this if you want to go to the top of a peak. You might not want to bring a stove at all. If you spill some boiling water on your hand, for example, you won’t have enough cold water to pour over the burn to stop the burning and ease the pain. You can get by just fine (or even be somewhat gourmet) with cold food.

GORP and hiking snacks includes no-cook meals.

TEETH

A temporary filling can be made by mixing zinc oxide powder and eugenol, or improvised from sugarless gum, candle wax or skiwax. Or ask your dentist for a commercially made temporary filling kit.

see also: injuries quick facts

1.Describe signs, symptoms and care for a head injury. Tell when to monitor victim for 24 hours versus when to evacuate

American Academy of Neurology

3 Grades of Concussion

Mild: No loss of consciousness and less than 15 minutes of symptoms, such as headache, vomiting, ringing in the ears, dizziness, confusion, memory lapse or blurry vision

Moderate: Same symptoms, but they last longer than 15 minutes. If they persist for longer than an hour, see a doctor. A stiff neck, convulsions and unusual sleepiness can signal something more serious, such as bleeding in the brain.

Severe: Loss of consciousness, even if for a few seconds.

Cause can be a sudden jolt to body as well as a hit in the head. Most heal themselves, but…

After a concussion: avoid sports for 2 weeks after symptoms disappear. Sustaining a second injury, no matter how minor, before the first one heals can lead to lingering symptoms such as amnesia, irregular sleeping, slurred speech, and unexplained depression.

Avoid alcohol and antihistamines for 2 weeks; any substance that can cause drowsiness can make it harder for doctors to diagnose the true problems.

Multiple concussions have a cumulative effect on brain tissue.

Even one minor concussion can make you four times more susceptible to another one.

NOLS Wilderness Medicine says “evacuation is recommended for any patient who has become unresponsive, even for a minute or two, or who exhibits vision or balance disturbances, irritability, lethargy, or nausea and vomiting after a blow to the head regardless of whether they were knocked out. A patient who exhibits loss of responsiveness but who awakens without any other symptoms may be walked out of the wilderness with a support party capable of quickly evacuating the patient if his or her condition worsens.” This could also apply after an earthquake.

See also concussion symptoms at: Concussion signs and symptoms, prevention

2.Demonstrate the modified jaw thrust method of opening the airway of a suspected spinal injury victim

3.List steps of a rapid, simple neurological examination to detect signs of stroke or head injury fast, basic neurological exam

4.Relate ways to assess an orthopedic injury without x-rays available

Common Signs and Symptoms of Musculoskeletal Injuries

Pain

Swelling

Deformity

Discoloration

Bone protruding from wound

Inability to use affected part

Grating bones

Snapping or popping sound

Cause of injury, such as fall from height

What surface did the climber who fell land on. . . soft, grassy surface -or- rock?

Did his rope slow the speed he fell at?

Was he properly wearing a helmet (nope, no baseball hat on under it) and did it stay on?

Did anyone see how far he fell and what part of his body he landed on and then bounced to?

5.Describe improvised back country splints and knee immobilizer

Using just a safety pin, you can fold up the bottom of a t-shirt and create a not-perfect sling.

Notice that in anticipation of uncomfortable swelling, his hand is higher than his elbow.

You could also put something stiff along the underside of the arm, and pad it.

See more ideas at NOLS (National Outdoor Leadership School) Wilderness Medicine Videos

https://www.nols.edu/en/resources/wilderness-medicine-resources/

6.Discuss wound management in the wilderness, the risks of and reasons to apply a tourniquet, how to improvise the irrigation of a wound and improvise a roller bandage

Your water purifying pump can clean water and provide a bit of water pressure to clean a wound with. (You might want to re-read the fiction about cleaning wounds with hydrogen peroxide to prevent infection at First Aid Facts and Fallacies.)

From Red Cross first aid station medical protocol

Refer to a physician for a tetanus shot:

Persons with minor, uncontaminated wound(s)

and no shot within 10 years.

Persons with major and/or contaminated wound(s) and no shot within 5 years.

All cases that may require stitches.

(Half of all soil samples test positive for tetanus spores.)

7.List common back country causes of and the RICE treatment of athletic injuries

… before a Triathlon we volunteered at, while the lifeguards were setting up gear, an athlete had dislocated his finger but the EMTs had not yet arrived so the guards were asked to give first aid. The athlete did not realize his finger would start to swell and had not taken off his wedding ring or elevated his hand to reduce the swelling. This could be even worse in a backcounty setting with no advanced help expected to arrive. (He chose to not have a cloth between his finger and the bag of ice.)

Anticipate swelling and remove jewelry.

and see below at:

J.Detail prevention of accidents and injuries in a wilderness environment

H. Discuss some of the difficult decisions that may have to be made when caring for a victim in a delayed-help situation

1.Name the steps for leaving a victim alone, including the recovery/drainage position

2.Practice deciding when and how to transport victim

Basic Guidelines for Moving a Victim

Only move a victim you can safely handle – practice with a not injured person first.

Bend at knees and hips

Lift with you legs, not your back

Take short steps

Move forward when possible

Look where you are walking

Protect victim’s head, neck, and back

3.Explain when to stop CPR and list times to continue CPR for over 30 minutes

also note:

Near-drowning victims have been successfully resuscitated after over an hour of submersion in cold water (5 to 10 degrees C). Favorable outcome is associated with young age, clean water, cold water, short immersion and pulse present or returning on scene with rescue breathing

ALL near-drowning patients who may have aspirated water must be evacuated. Even if victim feels okay it is possible to develop delayed problems.

I.Outline how a leader plans ahead for dealing with emergencies in the back country

At the Scene, Evaluate

Location

Problems

Dangers

Number of victims

Behavior of victims/bystanders, (worked together before? reacting to stress?)

Need for additional assistance

Ensure Your Safety By-

Evaluating potential dangers

Wearing proper gear

Doing what you are trained to do

Summoning additional resources

Obtaining consent

If a conscious, sane, sober adult does not give consent

DO NOT give care – but do call 911 if appropriate (and document lack of consent)

Implied consent means the victim would

agree to care if they could, such as

Unconscious victim

Confused or seriously ill

Mentally incompetent

Drunk

Actively drowning

Minor with no parent or guardian present (and has a life-threatening injury/problem)

Possible Dangers at an Emergency Scene

Crime

Traffic

Explosions, smoke/fire, gas or fuel leaks

Electricity, downed powerlines, you might need to turn off power / a circuit breaker.

Water/ice

Hazardous materials, broken glass

Unstable structures/vehicles

Natural disasters

Multiple victims

Hostile situations, including animals and people, (civil disturbances/riots, violent behavior and unruly fans at concerts or sporting events)

and especially during a wilderness emergency:

Hypothermia setting in because the victim is no longer hiking (skiing, moving around and creating body heat)

Dehydration will be setting in because you did not bring enough water/water filter (hmmm, and the victim was already dehydrated)

Victim exhibits altered mental status and victim shows behavior or personality changes / mood changes like feeling sad, anxious or listless or becoming easily irritated or angry for little or no reason. Might resist treatment. Mental status deteriorates, moving from disoriented, to irritable, to combative, to a coma

Swift-moving water, weather is getting worse / thunderstorm out of nowhere, daylight is fading, an avalanche after the first one that caused the injury, or another bunch of wasps after the first one(s) that caused the initial injury . . .

1.Identify resources and limitations: supplies, which party members have knowledge about region, trail, map and compass skills, pre-existing medical or physical limitations

Each person can write up important info and put it where others on the trip can find it if they become unconscious:

allergies (which food, medications, insects), medications currently used and with them on the trip (prescription, over-the-counter, herbal), medical conditions (Diabetic? Epilepsy? Asthma?), date of last Tetanus shot, blood type and any recent health problems, surgeries or injuries.

perhaps use a sample emergency information form.

2.Relate how to prepare with proper equipment including appropriate clothing, footwear, first aid supplies, devices for signaling and communication.

Depending on a GPS unit to intentionally be separated from your hiking partners can lead to confusion or even disaster. Be certain that the people you are with are happy with this prospect.

3.Describe additions to a standard first aid kit to prepare for backpacking

SAM Splint and bandages that will last (as likely shown in class)

aluminized flexible mylar emergency blanket

Trauma Shears – – heavy duty scissors to cut fabric without injuring the victim, with a wide, blunt tip instead of a sharp end.

Below see two pairs of scissors, one at the top of the photo with pointed ends and below it, with the yellow handle, note the blunt ends.

If the accident scene is messy, (with vomit, spurting blood or other body substances), you might want to consider putting on your rain gear and at least a bandanna across your nose & mouth. Plastic bags can be used in place of first aid gloves.

4.Discuss how to agree in advance upon decision making; which made by group, which by leader. Which unsafe actions are only the decision of the individual, which can be banned by the group

5.Relate details of how to get help: location of, and resources at, nearby trailheads, location of nearby phones and specific numbers to call for help, jurisdiction and resources of rescuing agency

Every overnight backcountry traveler should leave their itinerary with a friend and report in when they finish their adventure. If they do not report in the friend should know who to contact to go find them. Below is an example of what can go wrong when you don’t follow this basic advice:

from the NPS morning report

Yosemite National Park (CA)

Stranded Hiker Rescued From Park’s High Country

On November 10th, rangers learned that a solo backcountry hiker was overdue from a hike to an unknown location somewhere within the park. Steve Frazier had begun what he’d planned to be a five day trip in perfect weather on October 28th. Over the next three days, Frazier hiked more than 20 miles into the heart of the park’s wilderness. He set up camp at an elevation of 9,700 feet near Red Devil Lake as snow began falling on the evening of October 30th. This was the first significant storm of the developing winter season and it continued for three days, blanketing the High Sierra under nearly two feet of snow. The snow obscured the trail Frazier had been following, effectively trapping him at that location. He spent the next twelve days hunkered down in his tent, hoping to be rescued and rationing his remaining two days of food. Since Frazier had not told anyone of his plans, though, the rescue was long in coming. It was only after a list of missed commitments and appointments began to accumulate (including a missed plane flight home on November 9th), that questions regarding his whereabouts began to arise. Amazingly, searchers spotted the missing hiker and his camp from the air on their very first pass over the area and soon contacted a very happy Frazier, who was in remarkably good shape for someone who’d had almost no food for 12 days. Frazier made some initial bad decisions, particularly in his failure to leave a detailed route plan with someone who could report him overdue on an agreed-upon date, but made better decisions when the storm hit. He’d attempted to hike out, but didn’t go far before he realized that it was too difficult in deep snow and that he’d likely get into more trouble. So he stayed in his tent, rationed his food, stomped out an ‘SOS’ in the snow, used his pot as a shovel to keep a clear area around the tent, and above all kept a positive attitude. [Submitted by Keith Lober, Emergency Services Coordinator, Yosemite National Park]

J.Detail prevention of accidents and injuries in a wilderness environment

From National Outdoor Leadership School, (NOLS)

NOLS Common Problems

Majority of all injuries are athletic injuries, such as sprains, strains, etc. to knees, ankles and back from slips and falls around camp or when hiking

Common Causes of Athletic Injury on NOLS courses

Playing games such as hug tag and hacky sack

Tripping while walking in camp

Stepping over logs

Crossing streams, including shallow rock-hops

Putting on a backpack

Lifting a kayak or raft

Falling or misstepping while hiking with a pack (on any terrain)

Falling while skiing with a pack

Shoveling snow

Bending over to pick up firewood

1/3 of reported field incidents = wounds

Blisters are an everyday occurrence = moleskin, second skin, athletic tape

Most common illnesses are preventable gastrointestinal

— Disinfect water, wash your hands, waterless soaps can be useful when water is scarce

“Hypothermia, seizures, heat stroke and pregnancy occurred but with low frequency.”

Conditions most frequently requiring evacuation were: “fractures, dental emergencies, tick fever. athletic emergencies and non-specific body pains.”

Prevention is the best medicine:

careful gear selection to keep pack weight manageable

fitness, stretching, nutrition

careful walking helping each other over obstacles

stopping before you are tired

From Mountaineering First Aid (The Mountaineers, Seattle)

contributing causes of accidents from the American Alpine Club’s Accidents in North American Mountaineering

Bad judgment using equipment:

Climbing unroped

using inadequate equipment: no hard hat, etc.

failure of rappel

placing no or inadequate protection

Performance/judgment error:

exceeding abilities

climbing alone

loss of control on voluntary glissade

party separated, stranded

Environmental conditions:

bad weather

falling rock

darkness

avalanche

Equipment failure:

chock nut/pull out

ascender breakage

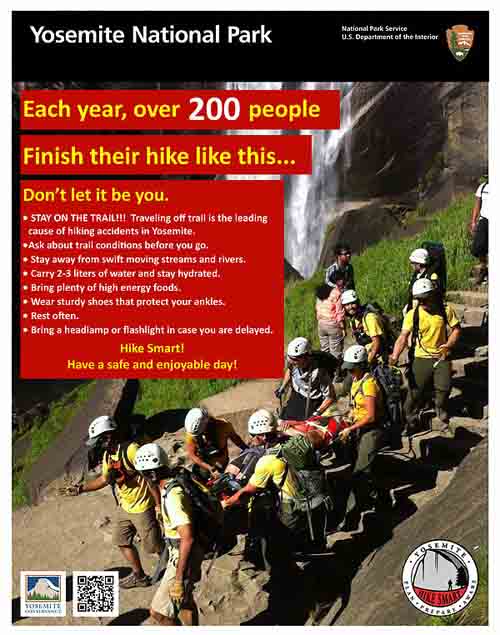

National Park Service Search and Rescue (SAR) Ranger John Dill wrote in climbing advice: Staying Alive

“. . . Fifty-one climbers died in Yosemite from traumatic injuries between 1970 and 1990. A dozen more, critically hurt, would have died without rapid transport and medical treatment. In addition, there were many serious but survivable injuries, from fractured skulls to broken legs (at least 50 fractures per year), and a much larger number of cuts, bruises, and sprains . . . ”

YOU CAN NOT ALWAYS EXPECT A RESCUE

National parks, (including Yosemite, where this photo was taken) have Search and Rescue teams ready at a moment’s notice to help accident victims.

“Yosemite Search and Rescue (YOSAR) can extract an ill or injured party out of the backcountry on crutches, by horseback, or even by helicopter, but in most cases, YOSAR utilizes a litter carry out team.”

But they can’t always get to victims in a hurry, or even get to them at all.

At the Grand Teton National Park Backcountry Camping page https://www.nps.gov/grte/planyourvisit/back.htm

There is a Backcountry Travel video

“to help plan your adventure to the high country in Grand Teton National Park.

Learn about safe travel, camping in bear country, clean camping practices and summer weather,”

that says, in part

“. . . you are responsible for your own safety when traveling in the back country.

If someone in your party has an accident or becomes seriously ill, stay calm and assess the situation. Provide first aid and establish a plan.

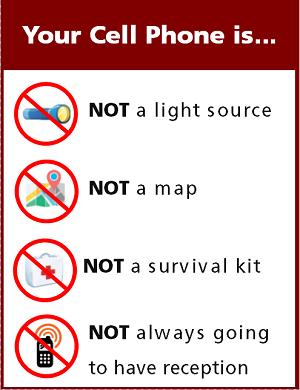

If you need help, rescuers will need to know the nature of the problem, and the patient’s location. Cell phone coverage is not reliable.

You may need to travel some distance to make a call or find assistance and remember, there is no guarantee of rescue.”

![]()

It can be good to plan in advance for accidents and illnesses. People who travel in the backcountry in minimum groups of four people can have one person stay with the victim, while two others go out together to get help (or find a place where their cell phone does function).

If you have a victim who has an ankle or foot injury, but can walk, you can divide the heavy items or even the entire contents of the daypack or backpack the victim was carrying among the other people in your group.

If they are still having trouble walking,

the walking assist pictured below can be used as described in the American Red Cross Lifeguarding Manual

in the section Moving a Victim – non-emergency moves:

“either one or two lifeguards can use this method to move a victim who needs assistance walking.

1/ Stand at one side of the victim, place the victim’s arm across your shoulders and hold it in place with one hand.

2/ Support the victim with your other hand around the victim’s waist.

3/ Walk the victim to safety.”

![]()

(Photo above taken in Grand Teton National park by Leeza Pushnof.)

You can have people assisting trade off the jobs of helping the person walk, or carrying heavy gear as you go along.

Do not expect to travel at the same speed as you would have just hiking. People should think safety by taking small steps and by stopping whenever the victim or people assisting want to or need to. If the trail has large steps, it might be best to have two people assisting, one on each side of the victim.

You could plan to stop regularly where there is a stream or lake to take the footwear off the victim’s foot/ankle and soak the injured part in the cold water of the stream / lake, just as you would apply a cold pack during more conventional first aid.

If the victim says that there is too much pain and they can not continue, they should be taken at their word. During an overnight backpack, if you can not get cellphone coverage, you might have to have an additional overnight stop since you will be moving slowly, so you should have always brought some extra food.

And note that you would not use this method to help “anyone you suspect of having a head, neck or spinal injury.”

And don’t aggravate injuries-(don’t move anything you think might be broken).

The Jenny Lake Climbing Rangers have said:

In the Event of a Life-Threatening Injury

Efforts should be made to obtain assistance as soon as possible. Cell phone notification is by far the most common method of notification. Calling Teton Interagency Dispatch (307-739-3301) directly will avoid potential confusion by eliminating the chance of your emergency call going to another county’s dispatch center. Program this number into your cell phone before your climb. If that number doesn’t work dial 911.

If cell phone service is not available, try sending a text to 911 or a friend or family member and have them call for help. Text messages require less signal strength and often transmit when cell phone calls cannot connect. Download the new BackcountrySOS App! https://www.backcountrysos.com/ BackcountrySOS is a simple-to-use smartphone app that allows you to quickly get your status and location information to emergency personnel.

If possible, send an extra member of your party or try to notify an adjacent party on the mountain, who can get to an area with cell phone reception or hike out to get word to the Jenny Lake Ranger Station (or any Visitor Center). Do not leave the injured climber alone unless absolutely necessary.

Information needed by the rescue team includes:

1) the exact location of the injured party

2) the time of the accident

3) the nature and extent of injuries & medical care being provided

4) equipment at the scene (ropes, hardware, first-aid kit, etc.)

5) the number of people with the injured party

6) the plan of action (if any).

read the entire current page of advice at: https://tetonclimbingaccidents.blogspot.com/

1.Differentiate between behavior toward black bears and grizzly bears, and show food storage safety factors.

How bears break into cars, what to do if you see a bear and more is at: Bears

Using a campsite food storage locker

your safety in grizzly bear territory tells you what to do if you see a bear in the distance or a bear charges you and has info about Bear Pepper Sprays and what might happen before a bison charges

You can read about safety at wildlife jams

Camping solutions for women has tips for and answers typical questions from first-time women campers, including the question: Can menstruating women camp or backpack around bears?

Rocky Mountain mammal size comparisons has pictures of a black bear and grizzly bear for comparison

2.Appraise contributing causes of mountaineering, traffic, hiking, water-related and animal related accidents typical to National Parks

Causes of accidents in Yosemite

stopping in the middle of the road to sightsee

Animals suddenly crossing the road

speed

narrow, slippery and winding roads

ignoring road warning signs

alcohol

didn’t anticipate slow-moving snowplow around the next curve

standing at the edge of rapids and waterfalls to get a better view

wading, swimming above waterfalls

unaware of the strength, speed of fast water

didn’t wear a lifejacket

tied rafts together

didn’t properly supervise children

ignored safety railings and warning signs

tried to imitate rock climbers

took shortcuts between hiking trails

tried to feed animals

got too close to get a photograph

Backpacker magazine quoted a ranger on the subject of trip safety:

“The death certificate usually says ‘killed by a fall’ or ‘died of exposure’ or some such thing,” says Butch Farabee, superintendent of Padre Island National Seashore, Texas, and the national Park Service’s search and rescue expert. “But it should read ‘killed by stupidity.’ Most people just don’t get it. The number one cause of injury and death is unpreparedness. You must always ask yourself, ‘What if?’ What if it rains for three days straight? Is my tent waterproof? What if I lose my compass? What if the rescue party doesn’t find me?”

The climbing rangers in Wyoming’s Grand Teton National Park agree. They’ve found that less than 1 percent of backcountry accidents are due to natural causes, like falling rocks, avalanches, and animal attacks. The rest are due to ‘pilot error.’ In other words, people don’t die from unexpected snowstorms; they die from not expecting and preparing for unexpected snowstorms.

Hiking Advice has hot weather hiking advice, hiking logistics and the answer to the question: When is the best time of day to cross a mountain stream?

3.Compare various methods of water purification

How to use a water purifying pump.

4. List the “Ten (or Fifteen) Essentials”

Essentials (from the Mountaineers):

Map of the area

Compass GPS is not infallible

Extra clothing, including raingear Improve your inexpensive rain gear

Sunglasses and sunscreen (5 sun protection factor is a joke, you need 30 plus)

Extra food and water

flashlight (electric torch) with extra batteries and bulb (and/or headlamp)

First aid kit with adequate supplies for heavy bleeding

candle or other Fire starter (cotton balls or dryer lint soaked in petroleum jelly, or some kinds of chips)

Matches in a waterproof container and a lighter

pocket knife

other essentials could include:

second (full) water bottle and a means to refill it, such as a water filter (filtering beats iodine or boiling)

Ice axe, crampons for glacier or snowfield travel (if required)

duct tape, some copper wire, safety pins, and other repair needs (but carefully checking gear and doing repairs before you leave can prevent the need)

insect repellant has answers to questions about

the percentage of DEET needed in an effective insect repellant, toxicity allergies, and more.

Signaling devices, whistle, mirror, a row of rocks pointing to you, (cell phone?) Cell phones in the wilderness) has advice on how/when to use a cell phone to contact 911 in the wilderness and a warning about interference between cell phones, iPods and avalanche beacons.

ground insulation, tube tent or other quick shelter

eyeglasses mini-repair kit

aluminized flexible mylar emergency blanket

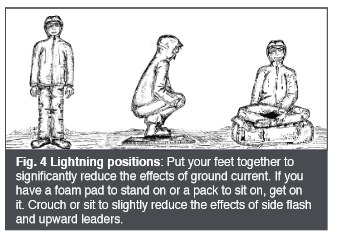

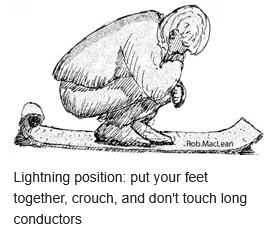

5.Describe safe and dangerous positions during a lightning storm

Weather.gov offers this drawing:

The park service offers this drawing of the lightning position:

During a thunderstorm, don’t take a shower or use a sink, including washing dishes. Don’t talk on a land line phone. Don’t use your I pod. Thunderstorm and lightning safety includes the answer to the question:

Why can’t you swim during a lightning storm? A strike on a lake doesn’t kill all the fish in the lake.

If someone gets hit by lightning, or even nearly hit, they may be thrown a distance, so if they need ventilations (also known as rescue breathing and/or artificial respiration) you’ll need to treat them as a spinal injury and use a modified jaw thrust rather than head-tilt chin-lift. If you are out in the wilderness, away from quick EMS help, you might need to give ventilations for a whole hour or even longer. Don’t give up if they still have a pulse.

Medicine for Mountaineering says:

“Clearly the emergency treatment for a lightning victim consists of immediate, and sometimes prolonged, artificial respiration. (Cardiac resuscitation should be given also, if needed, but the heart most often resumes beating on it’s own.) Over seventy percent of the persons struck by lightning have enough disruption of brain function to lose consciousness. Recovery of enough function to resume breathing commonly takes as long as twenty to thirty minutes, and occasionally takes hours.

If more than one person has been struck by lightning, which commonly occurs, attention should be directed first to the ones who are lying still, not breathing and appear dead. Those who are groaning or rolling around, although unconscious, are breathing and do not require immediate attention.”

You can reassure anyone who might have lost vision or has some paralysis that it is common with a lightning hit, and is usually temporary. Short term memory may be lost for a few days.

K.List basics of protecting and transporting a victim

1.Name factors in deciding whether and how to transport

2.Tell safety factors in a rescue helicopter landing area, and how and when to approach a helicopter

Yosemite Search and Rescue says of the approach of a rescue helicopter: “If ever in trouble, keep waving, even though the aircraft might be flying away from you; you don’t know which way everyone may be looking. Bright colors, reflective objects, and camera flashes are a few excellent tools for being spotted. Additionally, if you DON’T need help, please do not frantically wave at a rescue helicopter.”

The very basics are, if a helicopter comes to rescue you / a member of your group, stay away from where it is landing, any and all debris in the area will be blown around by the rotors. Your eyes and ears (and the victim’s) need protection. Wait for a crew member to come to you OR wait for the pilot to indicate it is safe to approach. Approach and depart in view of the pilot – do not run. Always approach from downhill in a crouching position. Never go near the helicopter rear tail rotor.

Helicopter safety video (yes, this starts with advertising having nothing to do with the subject: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Zzif-RSaQmE

You can’t always expect a helicopter rescue

You can’t always expect a helicopter rescue

_____________________________

Optional reading:

Yosemite Search and Rescue, lessons from the field:

http://www.nps.gov/yose/blogs/psarblog.htm

from Denali National park, Mountaineering Medical issues

http://www.nps.gov/dena/planyourvisit/part2medicalissues.htm

Boy Scouts Wilderness First Aid Curriculum and Doctrine Guidelines:

http://www.scouting.org/filestore/pdf/680-008.pdf

Search and Rescue can find you better if they know where you are.

IF you have cell phone coverage, you could tell them your location by latitude and longitude.

Find a compass, altitude, latitude and longitude on your cell phone here.

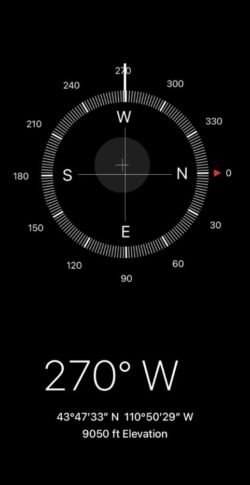

Knowing the elevation you attained on a hike and or climb can be fun for the been-there-and-done-that part of your adventure. Below, a photo taken of the compass app on a cell phone at Lake Solitude, Grand Teton National Park:

The 270 degrees W (west) shows the direction the cell phone was pointing, useful for orienting to a typographical map.

__________________________________

During any long hike or backpack,

To truly be able to leave no trace and follow backcountry rules about camping the proper distance from a lake or digging your personal latrine hole the proper distance from water, etc., you will need to know how far 100 or 200 feet is. Lay out a tape measure at home and walk it and count your paces.

How to poop in the woods.

![]()

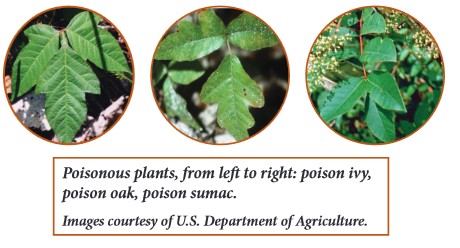

Photo above of poisonous plants, from left to right: poison ivy, poison oak, poison sumac,

and below red leaves of poison oak when they first emerge in early spring:

see info about protecting yourself, symptoms and first aid care: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/2010-118/pdfs/2010-118.pdf

“Approximately 50% to 75% of individuals react to urushiol, the allergic compound.”

![]()

Enhance your hike by reading:

The day hike gear section at Camping equipment checklist

Thunderstorm and lightning safety includes the answer to the question: Why can’t you swim during a lightning storm? A strike on a lake doesn’t kill all the fish in the lake.

backpacking advice has these sections: Must bring for each large group (or perhaps for each couple or person), Must bring backpacking for each person, Some (crazy?) people think these are optional for backpacking, Backpacking luxuries(?), Do not bring these backpacking, To keep down on weight backpacking, Don’t rush out and buy, BACKBACKING FOOD, Low-cook backpacking foods, Yosemite National Park WILDERNESS PERMITS, Leave no trace camping has these basic principles.

Cell phones in the wilderness which has advice on how/when to use a cell phone to contact 911 in the wilderness and a warning about interference between cell phones, iPods and avalanche beacons.

The use of cell phones for photography (with or without a selfie stick) has made preventable injury or even death by selfie common They were just taking a selfie . . .

Safe distances from wildlife includes reasons to stay away from even friendly seeming animals in parks and charts and photos to better be able to determine and visualize how far away from wildlife you need to stay to be safe (and obey laws that do have penalties).

Can a person who is prescribed an epi-pen risk going into the wilderness? and some sting prevention notes are at: Anaphylaxis quick facts

Crossing streams safely includes advice from Mount Rainier National Park, Yellowstone National Park, Great Smoky Mountains, and Yosemite National Park

see also:

Times to suspect a spinal injury (symptoms, causes, signs of spinal injury)

first aid for public safety personnel study guide

How to pass a Red Cross written test

Bloodborne Pathogens quick facts

first aid Secondary Assessment

causes of fainting, altered mental status, sudden altered mental status, unconsciousness

Seizures, causes of and basic care for

Concussion signs and symptoms, prevention

The author of this webpage, (written as a homework reading assignment for my students), does not give any warranty, expressed or implied, nor assume any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, product, or process included in this website or at websites linked to or from it. Users of information from this website assume all liability arising from such use.