All air has 21% oxygen.

At higher altitudes the barometric pressure is lower, so the effective oxygen is less.

At sea level the pressure is 160 mm hg and we have all the use of the 21% of oxygen.

At 5,000 feet the pressure is 130 mm hg and we have the effective use of 17% oxygen.

You will need to breathe deeper.

At 10,000 feet the pressure is 110 mm hg and we have the effective use of 14% oxygen, only two-thirds that of sea level.

At 10,000 feet the pressure is 110 mm hg and we have the effective use of 14% oxygen, only two-thirds that of sea level.

Besides needing to breath deeper, you may feel lightheaded or dizzy, very tired or get a headache.

Or you could get high-altitude cerebral edema (HACE), and high-altitude pulmonary edema (HAPE),

(see more about HACE or HAPE below),

which can be fatal unless people are aware of them and ready to descend to a lower altitude.

Descending is the required first aid for HACE or HAPE

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

People who live in Silicon valley are at 400 feet elevation.

When we camp at Yosemite valley we are at 4,000 feet elevation. At Tuolumne Meadows we are staying at 8,600 plus feet elevation.

Our hikes to the top of Yosemite Falls go to 6,700 feet and hikes to the top of Mount Hoffman go to 10,850′.

For trips to Grand Teton National park, most of us stay at 6,800 feet elevation, (Cascade Canyon, a hike many people try, has 7,900 – 8,000 feet elevation on the north fork trail and on the 8,000 to 9,900 on the south fork trail. Lake Solitude, a popular destination on the Cascade Canyon hike, is 9,050 feet elevation.

Yellowstone is 7,700 feet elevation, but hikes often take people to 9,000+ feet. (Mount Washburn is 10,219 feet.)

(The drive to Grand Teton can cross parts of Nevada (Elko) at 5,000 feet and Idaho (Pocatello) 4,400 feet. Sleeping at these altitudes on the drive can help people acclimate a little.)

(Not on our list of destinations: Everest Base Camp is 16,900 ft. – 5150m. Mt. Everest is 29,029 ft. – 8848m.)

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

You will probably feel out of breath at first and may even get a headache and lose appetite.

A mild headache is normal.

If the headache is worse in the morning after a night’s sleep you have trouble.

Shortness of breath when exerting yourself is normal.

If it progresses to shortness of breath when resting, you have trouble.

Avoid eating high fat, high protein near bedtime at least the first night, stick with high carbo evening snacks. You may lose your appetite, but you should eat. Sweet drinks are an ideal carbo supplement and water refill for people without an appetite.

Take it easy the first day.

Drinking lots of water helps.

Taking any kind of sleeping pills, which decrease respiratory rates, can make it worse. (This can include some kinds of allergy medications.) Alcohol or other depressants make it worse.

Being in good physical shape unfortunately is not protective against high-altitude illnesses.

__________________________________________________

Yosemite National park on Acute Mountain Sickness: “The most common altitude illness is also the mildest: AMS is characterized by a throbbing headache coupled with loss of appetite, fatigue or lassitude, shortness of breath, or insomnia. When symptoms of AMS develop, the best treatment is to stop the ascent, drink water, eat snacks, take medication for the headache, and rest. If the condition of the AMS patient does not improve, the group should descend at least 2,000 feet in elevation; someone suffering from AMS should never be left alone.”

__________________________________________________

NPS (Denali National park, where some climbers go to 20,310 feet elevation)

says:

“ACUTE ALTITUDE SICKNESS

Prevention

Gradual ascent

A highly effective means of preventing acute altitude illness is gaining no more than 500 meters (approximately 1,600 feet) in elevation per day (sleeping altitude) and including a rest day every 3 to 4 days.

Adequate hydration/nutrition

Maintaining adequate fluid and food intake does not directly prevent acute altitude illness. Instead, adequate hydration and nutrition is important in helping climbers’ function well at altitude and preventing the onset of symptoms of dehydration and malnutrition that can mimic symptoms of AMS.”

__________________________________________________

Centers for Disease Control on altitude sickness.

includes this:

“Altitude illness is divided into 3 syndromes:

acute mountain sickness (AMS), high-altitude cerebral edema (HACE), and high-altitude pulmonary edema (HAPE).

Acute Mountain Sickness

AMS is the most common form of altitude illness, affecting, for example, 25% of all visitors sleeping above 8,000 ft (2,500 m) in Colorado. Symptoms are similar to those of an alcohol hangover: headache is the cardinal symptom, sometimes accompanied by fatigue, loss of appetite, nausea, and occasionally vomiting. Headache onset is usually 2–12 hours after arrival at a higher elevation and often during or after the first night. Preverbal children may develop loss of appetite, irritability, and pallor. AMS generally resolves with 12–48 hours of acclimatization.

High-Altitude Cerebral Edema

HACE is a severe progression of AMS and is rare; it is most often associated with HAPE. In addition to AMS symptoms, lethargy becomes profound, with drowsiness, confusion, and ataxia on tandem gait test, similar to alcohol intoxication. A person with HACE requires immediate descent; if the person fails to descend, death can occur within 24 hours of developing ataxia.

High-Altitude Pulmonary Edema

HAPE can occur by itself or in conjunction with AMS and HACE; incidence is 1 per 10,000 skiers in Colorado and up to 1 per 100 climbers at more than 14,000 ft (4,270 m). Initial symptoms are increased breathlessness with exertion, and eventually increased breathlessness at rest, associated with weakness and cough. Oxygen or descent is lifesaving. HAPE can be more rapidly fatal than HACE.”

“Radial Keratotomy

Most people do not have visual problems at high elevations. At very high elevations, however, some people who have had radial keratotomy procedures might develop acute farsightedness and be unable to care for themselves. LASIK and other newer procedures may produce only minor visual disturbances at high elevations.”

“Diabetes Mellitus

Travelers with diabetes can travel safely to high elevations, but they must be accustomed to exercise if participating in strenuous activities at elevation and carefully monitor their blood glucose. Diabetic ketoacidosis can be triggered by altitude illness and can be more difficult to treat in people taking acetazolamide. Not all glucose meters read accurately at high elevations.”

__________________________________________________

An organizer for Yellowstone trips said:

“If you have diabetes, consider carrying the following with you to Yellowstone: twice as much insulin as is usually needed; extra syringes (or pump); a glucose meter with extra batteries and extra test strips; supplies to treat low blood sugar, such as glucose tablets or gel; other medications, such as glucagon; and a letter/prescription from a doctor (in the event extra insulin is needed). If you are participating on an overnight trip, be prepared to protect your insulin from freezing or overheating. . . some diabetics have reported having problems with their insulin pumps at altitudes greater than 8,000 feet.” (Please consult with your doctor before a trip to any high altitude.)

__________________________________________________

When the National Seniors Games were held in Albuquerque New Mexico

the athletes were given this info about altitude:

Welcome to Albuquerque . . . Our high desert altitude (around 5,000 feet) may have a warmer and drier climate, and the air may be a little thinner than you are used to.

While most athletes will not develop noticeable symptoms with the altitude gain, it is possible to experience a slight increase in respiratory and heart rate at rest. These are normal adaptations and here are some simple strategies to help minimize the differences.

ARRIVE EARLY Two extra days at altitude may help by allowing your body some time to acclimate.

STAY HYDRATED With a higher rate of breathing and drier air, one could dehydrate more quickly. Drink plenty of water during your downtime, practice and competition.The goal is to add water to your body, not deplete it. Plan on drinking more water here than you normally do at home.

MONITOR YOUR ALCOHOL INTAKE The effects of alcohol are greater at altitude than at sea-level including both intoxication and dehydration.

WATCH YOUR CAFFEINE INTAKE Caffeine can be dehydrating. This effect is greater at altitude as well.

REPLENISH ELECTROLYTES Foods high in potassium can help replenish electrolytes by balancing salt intake. These include: avocado, bananas, potatoes, tomatoes and spinach.

PLAN FOR SUNSHINE Increased altitude means less protection from the sun. Sunscreen is a must, and don’t forget to protect your lips (balm) and eyes (sunglasses) too!”

__________________________________________________

From the Yosemite Daily Report:

According to the American Academy of Dermatology, sunburns develop more quickly at high altitudes. A study compared the sun’s ultraviolet energy in three locations; Vail, Colorado; New York City; and Orlando, Florida. UVB rays were most powerful in Vail, the highest of the three locations. For each 1,000 feet of elevation, the intensity of ultraviolet light increases by 8 to 10 percent. In Vail, the potential to cause sunburn was less than half the time as in Orlando, even though Orlando is much closer to the equator.

Follow these tips to protect you from the suns damaging rays:

Use a broad-spectrum sunscreen with an SPF of at least 15 on all exposed

skin, including the lips, even on cloudy days.

Apply sunscreens at least 30 minutes before going outside.

If exposed to water, either through swimming or sweating, a

water-resistant sunscreen should be used.

Reapply sunscreen frequently – every 1 1/2 hours, more often if sunny or heavily perspiring.

Wear a broad-brimmed hat and sunglasses.

Seek shade whenever possible.

Wear protective, tightly-woven clothing.

Plan outdoor activities early or late in the day to avoid peak sunlight hours between 10 am and 4 pm” (Glenn Dean)

__________________________________________________

Be sure to apply sunscreen to the underside of your chin, underside of and just up into your nose to protect from sun reflected off water, snow or granite.

Some brands of sunscreen can be applied right before going into the water, but read the directions.

Some will wash off and make an oil slick if you put them on less than twenty minutes before swimming.

__________________________________________________

why your tent mate might seem to stop breathing

In Medicine for Mountaineering, we find a discussion of sleep periodic breathing at high altitude.

“Is almost universal at altitudes above 13,200 feet and may occur at lower altitudes (above 6,600 feet). The typical pattern begins with a few shallow breaths, increases in depth to very deep, sighing respirations, then falls off rapidly. Respirations can cease for five seconds or more before shallow breaths resume and the pattern is repeated. An observer may fear that the person is not breathing at all.

“During the period when breathing has stopped, the person often becomes restless and sometimes awakens with a sense of suffocation…it is so common at high altitude that it should not be considered abnormal...however it may be a sign of a serious disorder if it occurs for the first time during an illness or after an injury, particularly a head injury.”

__________________________________________________

Any hike to the top of peaks and domes must start early so we can get to the top and back down before expected afternoon lightning storms start. If at any point thunder is heard or lightning seen, you should turn back from the top of any peak, even if you haven’t gotten as far as you wanted. Don’t get zapped! Don’t use your cell phone or IPod. Thunderstorm and lightning safety has details.

Any hike to the top of peaks and domes must start early so we can get to the top and back down before expected afternoon lightning storms start. If at any point thunder is heard or lightning seen, you should turn back from the top of any peak, even if you haven’t gotten as far as you wanted. Don’t get zapped! Don’t use your cell phone or IPod. Thunderstorm and lightning safety has details.

__________________________________________________

For students in HLTH57A,

reading the rest of this page is optional.

__________________________________________________

a test for Acute Mountain Sickness (AMS)

One of the scoring systems to determine if the altitude is getting to you (slow down a little for awhile) or really getting to you (you need bedrest at a lower elevation), is the Lake Louise Acute Mountain Sickness (AMS) Score. It was developed for research, but can be used to give mountaineers a warning of trouble.

The only real first aid for Acute Mountain Sickness is to descend to a lower altitude.

Are you one of those people who ignores shivering(hypothermia)until it is severe? AMS can turn into life-threatening High Altitude Pulmonary Edema (fluid is leaking into your lungs) or High Altitude Cerebral Edema (your brain is swelling) quickly.

Don’t be so brave and ignore other than mild symptoms.

Take this test:

Remember that the symptoms are quite the same as those of a hangover, intoxication or the flu, so rule these out first.

Self Report Questions:

Headache

0 No headache

1 Mild headache

2 Moderate headache

3 Severe, incapacitating headache

Gastrointestinal symptoms

0 No gastrointestinal symptoms

1 Poor appetite or nausea

2 Moderate nausea or vomiting

3 Severe, incapacitating N & V

Fatigue and/or weakness

0 Not tired or weak

1 Mild fatigue/ weakness

2 Moderate fatigue/weakness

3 Severe fatigue/ weakness, incapacitating

Dizziness / lightheadedness

0 Not dizzy

1 Mild dizzy

2 Moderate dizziness

3 Severe dizziness, incapacitating

Difficulty sleeping

0 Slept as well as usual

1 Did not sleep as well as usual

2 Woke many times, poor night’s sleep

3 Could not sleep at all

What your score means:

If you recently went up in altitude from where you are used to (example, most Outdoor Club people live at around 400 feet altitude, but when we go to the Sierras or the Tetons we often travel starting at 8,000 feet altitude).

and if you have a headache

and at least one other symptom from the five groups above

and a total score of at least 3

(although some researchers say a score of 4 minimum), then you have AMS and you need to slow down.

Hikers, backpackers, climbers and other high country travelers usually use the five question test above.

These below are used more by researchers, but are of interest as well.

As you can tell by the symptoms, scores of 2s, 3s and 4s are big trouble that needs attention immediately.

Clinical Assessment:

Change in mental status

0 No change in mental status

1 Lethargy (sluggish) /lassitude (weariness of mind)

2 disoriented/confused

3 Stupor (mental apathy) / semi conscious

Ataxia (Loss of coordination of muscles, as judged by ability to walk heel-to-toe with eyes open. If you have any reason to doubt someone’s ability to do this, have two people stand on either side of them as they try).

0 No ataxia

1 Maneuvers to maintain balance

2 Steps off line

3 Falls down

4 Can’t stand

Peripheral edema (such as swelling of hands or feet)

0 No peripheral edema

1 Peripheral edema in one location

2 Peripheral edema in two or more locations

__________________________________________________

In an article in the San Francisco Chronicle in 2003, Study changes attitude about altitude

“High altitude pulmonary edema (HAPE) is a serious, scary disease — and one that doctors generally believed wasn’t much of a problem for healthy people traveling to elevations below about 9,000 feet.

But a new study published last month in Chest, a journal devoted to cardiopulmonary and critical care, found the condition — marked by fluid in the lungs and fatal if left untreated — occurring as low as 5,000 feet above sea level. That’s lower than Lake Tahoe, with an elevation of 6,229 feet. The findings suggest that what may have been diagnosed as pneumonia among skiers, snowboarders and other alpine visitors could actually be HAPE.”

You cna read the whole article at:

http://sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?file=/chronicle/archive/2003/02/16/TR221535.DTL

__________________________________________________

From the National Park service, incidence of high altitude sickness in various groups:

Skiers who reached a maximum altitude of 11,500 feet, but who slept at 7,000 feet, 15-20% had Acute Mountain Sickness (AMS), who slept at 8,500 feet, 25% had AMS, at 10,000 feet 25-40% had AMS. Less than 1% had HAPE or HACE.

Mount Rainier climbers who took 1-2 days (they flew in, then climbed) to get to the peak, and who reached a maximum altitude of 14,405 feet but slept at 10,000 feet: 67% had AMS and less than 1% had HACE or HAPE.

Mt. Everest trekkers who flew in, slept at 10,000 to 17,000 feet and went to a maximum altitude of 18,000 feet: 47% had AMS and 1.6% had HAPE or HACE 1.6%. Those who took 10-13 days walking (same altitudes slept at and reached) 23% had AMS, 5% HAPE or HACE.

__________________________________________________

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

(Note to on-line users not in my classes: this is a study sheet.

It is not complete instruction in first aid or the topic named in the webpage title.)

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

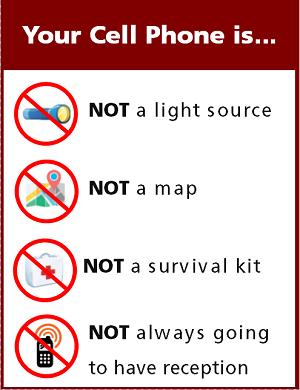

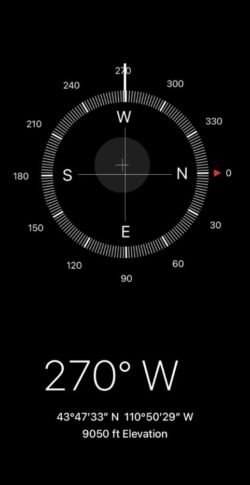

Search and Rescue can find you better if they know where you are.

IF you have cell phone coverage, you could tell them your location by latitude and longitude.

Find a compass, altitude, latitude and longitude on your cell phone here.

Knowing the elevation you attained on a hike and or climb can be fun for the been-there-and-done-that part of your adventure. Below, a photo taken of the compass app on a cell phone at Lake Solitude, Grand Teton National Park:

The 270 degrees W (west) shows the direction the cell phone was pointing, useful for orienting to a typographical map.

__________________________________

Want to read even more?

Travel At High Altitude http://www.medex.org.uk//medex_book/about_book.php (usually printed in as many as a dozen languages).

“Symptoms of dehydration and malnutrition can mimic symptoms of Acute Mountain Sickness”

Mountaineering Medical Issues

https://www.nps.gov/dena/planyourvisit/part2medicalissues.htm

__________________________________________________

see also:

GORP and hiking snacks includes no-cook meals. Consider this if you want to go to the top of a peak. You might not want to bring a stove at all. If you spill some boiling water on your hand, for example, you won’t have enough cold water to pour over the burn to stop the burning and ease the pain. You can get by just fine (or even be somewhat gourmet) with cold food.

Thunderstorm and lightning safety includes the answer to the question: Why can’t you swim during a lightning storm? A strike on a lake doesn’t kill all the fish in the lake.

Hiking Advice has hot weather hiking advice, hiking logistics and the answer to the question: When is the best time of day to cross a mountain stream?

You can’t always expect a helicopter rescue

You can’t always expect a helicopter rescue

Cell phones in the wilderness which has advice on how/when to use a cell phone to contact 911 in the wilderness and a warning about interference between cell phones, iPods and avalanche beacons.

The use of cell phones for photography (with or without a selfie stick) has made preventable injury or even death by selfie common They were just taking a selfie . . .

Can a person who is prescribed an epi-pen risk going into the wilderness? and some sting prevention notes are at: Anaphylaxis quick facts

backpacking advicehas these sections: Must bring for each large group (or perhaps for each couple or person), Must bring backpacking for each person, Some (crazy?) people think these are optional for backpacking, Backpacking luxuries(?), Do not bring these backpacking, To keep down on weight backpacking, Don’t rush out and buy, BACKBACKING FOOD, Low-cook backpacking foods, Yosemite National Park WILDERNESS PERMITS, Leave no trace camping has these basic principles.

Enhance your drive to your next adventure: Road trip advice and etiquette

Rocky Mountain mammal size comparisons

Rocky Mountain mammal size comparisons

Camping solutions for women has tips for and answers typical questions from first-time women campers, including the question: Can menstruating women camp or backpack around bears?

Your safety in grizzly bear territory

Where were they when they got that great picture in Yosemite?

Where can I take a photo that looks like the one on a Yosemite postcard I just bought?

Places to take photos of Half Dome, Bridalveil Fall, El Capitan, Yosemite Falls and Staircase Falls.

______________________________________

(Note to on-line users not in my classes: this is a study sheet. It is not complete instruction in first aid or the topic named in the webpage title.)

The author of this webpage, (written as a homework reading assignment for my students), does not give any warranty, expressed or implied, nor assume any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, product, or process included in this website or at websites linked to or from it. Users of information from this website assume all liability arising from such use.