Note to on-line users not in my classes: this is a study sheet. It is not complete instruction in first aid, precautions for allergic reactions or how to use an epi-pen.

See a cautionary tale from Yosemite National Park about remembering to pack your medications at the end of this webpage.

Anaphylaxis (severe allergic reaction)

Swelling of air passages restricts breathing

Usually occurs suddenly

Triggered by-

- Food (commonly – nuts, shellfish, coconut oils, strawberries)

insect stings

animal dander

pollen

medications (antibiotics, sulfa,)

unknown causes

reactions can be mild to severe – death may occur if a person’s breathing is severely restricted

——————————————————————-

Common Asthma Triggers

https://www.cdc.gov/asthma/triggers.html

——————————————————————-

Signs and Symptoms

Signs and Symptoms of Anaphylaxis

- Hives

Itching

Rash

Weakness

Nausea/vomiting/ stomach cramps

Metallic taste or tingling in mouth

Dizziness, fainting or sudden weakness

Trouble breathing that includes coughing and/or wheezing

Tightness in chest/throat

Swelling of face/neck/tongue

a sense of doom

Care for Anaphylaxis

- Call 911 immediately if the person has the above symptoms, is having trouble breathing or if the person says that his/her throat is closing

If you are alone, and no one else can make the call, help the person with their medication for the emergency treatment of anaphylaxis (Epinephrine is a drug that slows or stops the effects of anaphylaxis) and then call.

Please note it says “help the person with their medication”. You should never share your own personal medications, including epinephrine, no matter how much you think the victim should have them.

Position victim in the most comfortable position that aids breathing. (Down on the floor, not sitting up on a chair / stool. Potentially laying down if showing symptom of shock)

Administer supplemental oxygen

Care for Respiratory Distress

Have victim rest in comfortable position

Keep victim from getting chilled or overheated

Reduce heat; add moisture

If authorized, help victim take any medications

Summon more advanced medical personnel

Monitor vital signs

—————————————————————————-

Prevention notes:

Brightly colored clothing, flowery prints and black attract insects more than white, green, tan or khaki without prints/patterns. Wear shoes and keep arms and legs covered if possible. Long-sleeved shirts and pants work to some degree 24 hours a day, but we counted fifty mosquitos in my husband’s back during a lunch stop up on a Mount Rainier trail.

In brush, put your socks up over pant legs.

Perfumes in lotion, suntan lotion, deodorant and other cosmetics attract.

Don’t bring clothes camping that have been rinsed or dried with mosquito-attracting scented softeners (plus, dryer sheets can make a greasy stain on clothes if they get stuck to them, and the softeners can decrease the lofting and wicking of garments).

If you use scented room air fresheners, all your clothes (think jackets you might not launder that often) will have the sent and can attract insects you do not want to visit you.

My allergist told me to take vitamin B1 for a month before camping trips, but a brochure on West Nile virus from the Santa Clara County (California) Vector Control District said “Vitamin B1 and ultrasonic devices are not effective in preventing mosquito bites.”

Along with adults wearing long sleeved clothing and using an effective repellent, it recommends “place mosquito netting over infant carriers when you are outdoors with babies.”

Food attracts, store it in closed containers; avoid open garbage receptacles.

A fact sheet on the subject of yellow jackets from the Santa Clara Valley Urban Runoff Pollution Prevention Program said, in part:

“Outdoors do not drink soft drinks or other sugary drinks from open containers. Use cups with lids and straws, and look before you sip. Do not carry snacks containing meat or sugar in open containers.

Avoid going barefoot, (or even wearing just flip-flops) especially in vegetation. Closed-toed shoes that fully cover your feet are best.

Do not squash a yellowjacket. When crushed, many yellowjacket species emit a chemical that can cause other nearby yellowjackets to attack.

Always examine wet towels or wet clothing before you pick them up outdoors.”

When camping, shake out your sleeping bag before going to sleep.

insect repellant has answers to questions about the percentage of DEET needed in an effective insect repellant, toxicity allergies, and more.

—————————————————————————-

Can a person who is prescribed an epi-pen risk going into the wilderness?

Be sure your travel companions know about your allergies, reactions you have previously had and where you keep your (easily accessible, not buried way down in a dry bag) medications.

Be sure you get thorough training from your doctor on when and how to use your epipen(s). There have been adverse reactions, including fatalities, due to inappropriate route of administration or excessive doses.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has made updates to the patient instructions for epinephrine auto-injectors:

http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2016/019430s061lbl.pdf

Consult your doctor first, asking:

if you need to also carry Diphenhydramine and Prednisone, under what circumstances you would use them,

how many epinephrine doses you should carry, and specific details of when/how you would use more than one. (According to a manufacturer, as many as 35% of people need more than one dose to stop a severe allergic reaction, and the effects of a dose can last for as little as ten minutes. But epinephrine is a powerful cardiac stimulant that if overused can cause severe problems even for people with normal hearts and can be extra dangerous to diabetics.)

(A study quoted in the journal Circulation “demonstrated that 20% of anaphylactic reactions are biphasic, with a mean of 10 hours between 2 symptomatic episodes.”)

how to store your epi-pen from heat/cold/direct sunlight/breakage

Get the instructions your doctor gives you in writing and consider passing them on to your traveling companions in case they need to help you.

Take a look at your prescription for discoloration or solid particles and re-check the expiration date well before leaving town in case you have to replace it.

you also might want to have more than one set, in two different dry bags, on a trip kayaking.

Yosemite Search and Rescue recommends: “Recreating with medical conditions: Medical conditions should not prevent recreationists from enjoying Yosemite’s vast wilderness; however, proper management of medical conditions is essential for a successful wilderness experience. Whether hiking in a party of two or ten, it is important for fellow hiking companions to be aware of medical conditions in the group and proper treatment and management of medical conditions. Recreationists who are prescribed medication should carry the medication (plus a few extra doses) in a personal pack so that they don’t miss a dose if an outdoor outing goes awry or longer than anticipated.”

and ask your doctor if these these precautions/guidelines apply to you:

(from Boy Scouts of America Wilderness First Aid Curriculum and Doctrine Guidelines, 2017 Edition)

“A severe reaction, known as anaphylaxis, is a true emergency. At first, there may be signs and symptoms of a non-life threatening reaction. Anaphylaxis may then produce shock but is more often typified by extreme difficulty breathing, causing the sufferer to be unable to speak or to speak only in one- or two-word clusters. Swelling of the face, lips, tongue, and perhaps the hands and feet are indicative. These signs and symptoms can appear in as little as five minutes and most often within 45 minutes to one hour. Death is imminent. Anaphylaxis is reversible only by an immediate injection of epinephrine (adrenaline). Epinephrine reverses the effects of an overproduction of histamines. Injectable epinephrine is

available commercially, and by prescription only, in spring-loaded syringes that function when pressed into the thigh. You may need to assist someone with the injection. Injections can be repeated if the first one fails or a relapse occurs . . . Individuals on trips who are susceptible

to anaphylaxis should carry at least three injections of epinephrine.”

Use of an EpiPen® Auto-Injector

The EpiPen®

is an auto-injection system with two injection units available per box. It is available in adult and child doses.

Using the EpiPen® involves three simple steps:

1. Pull off the blue safety cap.

2. Place the orange tip on the outer thigh, half-way between the hip and knee (lateral side)—preferably against the

skin, although it can be used through thin clothing.

3. Push the unit against the thigh until it clicks, and hold it in place for a count of 3.

4. Rub the injection area for 10 seconds.

After injection of epinephrine, and when the patient can breathe and swallow easily, an oral antihistamine should be given, following the directions on the label, to continue suppressing the overproduction of histamines. The patient should also be kept well-hydrated.

Everyone who knows they are susceptible to severe allergic reactions should carry injectable epinephrine. Epinephrine can be ruined by extremes of cold and heat and needs to be protected from these extremes.

Guidelines for Prevention of Allergies and Anaphylaxis

Every precaution should be taken to avoid contact with allergens. Trip leaders who know of anyone in their party susceptible to severe reactions should avoid taking known allergens on the trip. Individuals on trips who are susceptible to anaphylaxis should carry at least three injections of epinephrine.

Evacuation Guidelines

Mild to moderate reactions can be managed in the field and do not require evacuation. Anyone treated for anaphylaxis should be evacuated rapidly—go fast. During evacuation, the patient should be well-hydrated and kept on a regimen of oral antihistamines.

___________________________________________________________________________

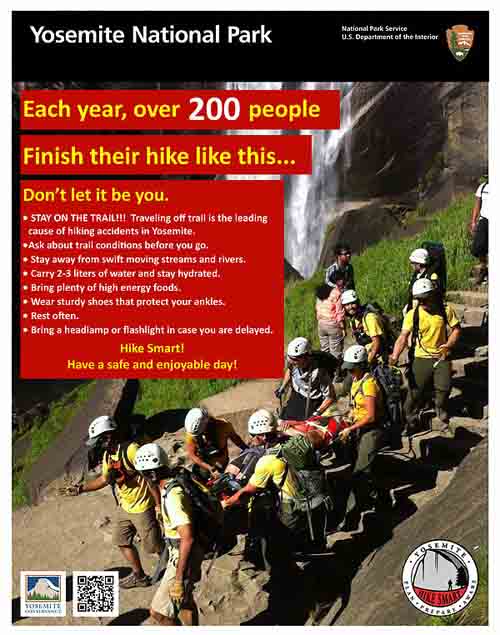

From the First Aid Kit to the Helicopter

September 11, 2015 from Yosemite National Park Search and Rescue blog

If you find yourself in a helicopter over the Yosemite landscape, something has gone terribly wrong. On Saturday, June 13, at a few minutes before 10 am, two hikers ran down Half Dome’s subdome to the permit check point. They reported that a female hiker halfway up the subdome was having a severe allergic reaction, including facial swelling, vision loss, and, most concerning, difficulty breathing. They reported she had eaten something she was allergic to. The rangers contacted dispatch and ran up the trail.

Let’s rewind to better understand how this happened. Our hiker was headed out for the hike of a lifetime. She and her best friend were the proud winners of Half Dome permits! So they headed out early to beat the midday heat. Along the way, they wisely stopped to refuel. Her choice of snacks included an energy bar, which contained some tree nuts. The hiker was “technically” allergic to them, but had eaten them many times before in small amounts with no problem. While her doctor had prescribed her an EpiPen just in case, she had never needed to use it. (An EpiPen contains epinephrine, a lifesaving drug that reopens airways that are swelling shut due to an allergic reaction known as anaphylaxis.) But hiking Half Dome is not something she did regularly and it put stress on her body that it didn’t normally experience; the allergy flared like never before. Her extremities and face swelled. Her vision went. She started to pass out and collapse. But in her first aid kit, she had no epinephrine or antihistamine (e.g., Benadryl).

By the time rangers reached the scene, bystanders had supplied antihistamine, which stopped the allergic reaction. But the hiker was in bad shape and her hike was over. The rangers called for the helicopter and moved her to a landing zone, where a helicopter picked her up and transported her to the Yosemite Medical Clinic.

The wilderness can be unpredictable and it is best to stack the deck in your favor by preparing for your hike and taking the essentials. (This is also true when you’re just driving around or taking short walks in the frontcountry.) One of those essentials is a first aid kit. People debate endlessly about what is or isn’t necessary for a particular kit in a particular set of circumstances. But not up for debate are those medications prescribed by doctors that you must take at regular intervals or need in case of an emergency. Examples include: asthma medication, epinephrine and antihistamine, medications for heart conditions like angina, medications and testing equipment for diabetes, and any other medication you must take at a regular interval. You never know when you might be delayed due to weather, because you got lost or injured, or because the hike just takes longer than expected.

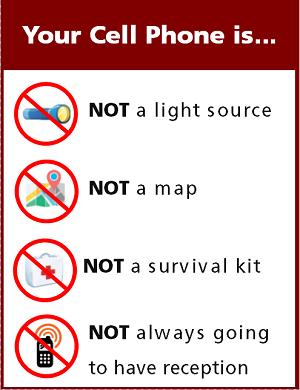

Even a 15-minute walk up to view Bridalveil Fall is too far to be from life-saving medications should you be allergic to bees and get stung. Your first aid kit won’t be helpful if it’s incomplete or too far away. Cell reception is too spotty to be reliable. A ranger who can help or call in more help may be miles away when minutes are precious.

No matter how short the hike or how close the car is, stack the deck in your favor. Prepare before you hit the trail. Pack the essentials. Take your medication. Hike Smart!

________________________________________________________________

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

(Note to on-line users not in my classes: this is a study sheet.

It is not complete instruction in first aid or the topic named in the webpage title.)

The author of this webpage, (written as a homework reading assignment for my students), does not give any warranty, expressed or implied, nor assume any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, product, or process included in this website or at websites linked to or from it. Users of information from this website assume all liability arising from such use.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

see also:

How to pass a Red Cross written test

Oxygen administration quick facts

first aid Secondary Assessment

Times to suspect a spinal injury (symptoms, causes, signs of spinal injury)

causes of fainting, altered mental status, sudden altered mental status, unconsciousness

Seizures, causes of and basic care for

Concussion signs and symptoms, prevention

Enhance a hike by reading:

The day hike gear section at Camping equipment checklist

You can’t always expect a helicopter rescue

You can’t always expect a helicopter rescue

Thunderstorm and lightning safety includes the answer to the question: Why can’t you swim during a lightning storm? A strike on a lake doesn’t kill all the fish in the lake.

backpacking advice has these sections: Must bring for each large group (or perhaps for each couple or person), Must bring backpacking for each person, Some (crazy?) people think these are optional for backpacking, Backpacking luxuries(?), Do not bring these backpacking, To keep down on weight backpacking, Don’t rush out and buy, BACKBACKING FOOD, Low-cook backpacking foods, Yosemite National Park WILDERNESS PERMITS

see also: Cell phones in the wilderness which has advice on how/when to use a cell phone to contact 911 in the wilderness and a warning about interference between cell phones, iPods and avalanche beacons.

The use of cell phones for photography (with or without a selfie stick) has made preventable injury or even death by selfie common They were just taking a selfie . . .

Leave no trace camping and hiking has these basic principles:

Plan Ahead and Prepare

Travel and Camp on Durable Surfaces

Dispose of Waste Properly

Leave What You Find

Minimize Campfire Impacts

Respect Wildlife

Be Considerate of Other Visitors

During any long hike or backpack,

To truly be able to leave no trace and follow backcountry rules about camping the proper distance from a lake or digging your personal latrine hole the proper distance from water, etc., you will need to know how far 100 or 200 feet is. Lay out a tape measure at home and walk it and count your paces.

How to poop in the woods.